Contents

Guide

Page List

CONTENTS

A Winter Memory and A Description of the Enemies of Bees, Old and New

A Sign of Spring Remembered and Older Descriptions of the Cleansing Flight and the Reactions of Neighbours

A Feisty Californian Beekeeper Remembered and An Update on the Progress of the Killer Bee

Various Kinds of Guests at the Hive Remembered and A Survey of What People Have Believed We Could Learn From Bees Through The Ages

A Visit to Lennart and His Girls Remembered and Answers to the Questions: Why Do Bees Sting?, How Are Bee Stings Best Treated? and Is Protective Clothing Necessary?

A Swarm that Caused Problems Remembered and Accounts of Rows between Neighbours and How People Dealt with Swarms in the Past

A Walk in Yorkshire Remembered and A Comparison between Heather and Chestnut Honey

A Honey Tasting and a Lecture on Honey Remembered and A Description of Todays Honey Fraud

A Tricky Question Recalled and Repeated Attempts to Understand Rudolf Steiners Thoughts on Bees

Brother Adam Remembered and His Posthumous Reputation and the Scandal He Managed to Miss

A Trip to Paris Remembered and A Report from the Village of lghult

A Mysterious Honey Remembered and The Art of Tasting the Difference between One Honey and Another

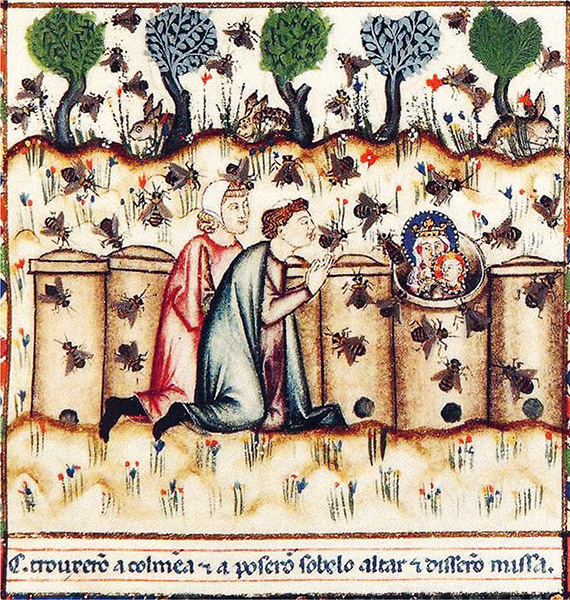

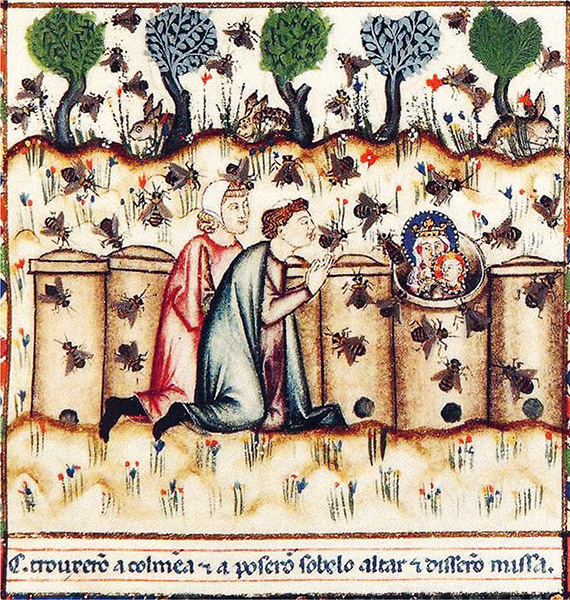

THE MIRACLE OF THE WAFER IN THE BEEHIVE

In most ancient cultures the bee was associated with religion and the divine. A symbol of virginity in medieval Catholicism, bees were believed to be parthenogenetic and many edifying legends associated them with the Holy Virgin. One of them concerned a farmers wife who, instead of swallowing the wafer that the priest had given her during mass, had hidden it under her tongue before taking it home and stuffing it inside the log hive (that was how they made hives at the time) to attract more bees and therefore produce more honey and wax. But when she and her husband opened the log they discovered that the wafer had been miraculously transformed into Mary and the Baby Jesus.

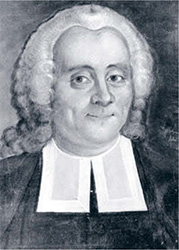

SAMUEL LINNAEUS THE BEE-KING FROM THE SWEDISH PROVINCE OF SMLAND

The honeybee got its Latin name Apis mellifera, which means the honey-bearing bee, from Carl von Linn, known outside Sweden as Linnaeus. But as Samuel, his younger brother by eleven years, would point out, bees did not carry home ready-made honey, rather the nectar that they would then process to make it. Its name should really be Apis mellifica, the honey-making bee. The rules of nomenclature did not, however, allow for this change to be made.

Samuel Linnaeus was born in 1718 in Stenbrohult. He took over from his father as vicar before becoming a dean, and eventually one of the pioneers of Swedish agriculture. By the time his book, Kort men Tillfrlitelig Bij-Sktsel (A Brief but Reliable Guide to Beekeeping), was published in 1768, he had been keeping and studying bees for thirty years. It had a huge impact and is still worth reading.

In Egyptian mythology bees came from the tears of the sun god Ra when they fell on the desert sands. According to Greek and Roman authorities, including Virgil, they came into being in the rotting carcasses of oxen. This belief was called begunia and survived into the Middle Ages and even later. It was not until the eighteenth century that it was understood that the queen bee laid eggs after mating.

INTRODUCTION

The happiness of the bees and the dolphin is to exist.

For man it is to know that and to wonder at it.

Jacques Cousteau (19101997

The Roman writer Pliny believed the honeybee was the only insect created for the sake of man, a view that would prevail for a very long time and that can still be encountered today. Bees do not just give us honey and wax; they also set an example in terms of hard work, altruism and how to construct an efficient society. These winged Aeolian harps can provide us with amusing company during our leisure which leads to wholesome observations and a refined mood, wrote the Swedish parson Fredrik Thorelius in the mid-nineteenth century, and his sentiments were typical of the period. Just as typical, though of a later era, is this observation by the Danish writer Jrgen Steen Nielsen made in 2017:

We fancy ourselves the most intelligent of creatures. But intelligence encompasses many different things, including the ability to ensure a communitys survival and its stability by employing a capacity to listen, collaborate and focus on the common good. If we fail to learn more of these qualities from the bees, who have far greater experience, we will lose first the bees and then ourselves.

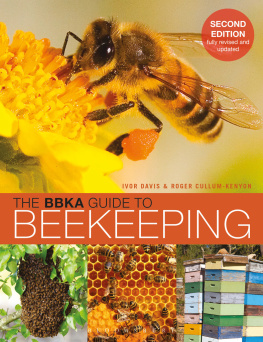

In the past keeping bees was an unquestioned part of subsistence farming. As was the custom at that time, Karl-Bertil and Anna Lovisa Johansson in Sdra Vi protected their hives against rain and foul weather with hoods made of the bark of a spruce.

But bees exist no more for our sake than any other element of nature does. We, however, have made ourselves dependent on them. We can get by without their products if necessary, but most of what we eat derives from crops that are pollinated by insects, including the honeybee. And yet we have made things so difficult for them that their very survival is now in doubt. How did that happen?

In the past, agriculture was more diverse; the natural world was rich in different species and if you lived on the land, beekeeping was part of your existence. But as heather moors and heaths, pastureland and the places people lived have been replaced by plantations of conifers, while flowery meadows have been turned to arable land or simply cleared, rich sources of nectar and pollen have disappeared. The countryside has been depopulated, and fewer people keep bees.

The monocultures of today, oilseed rape cultivation in particular, provide huge amounts of nectar for a few weeks but nothing for the bees to live on over the rest of the summer. The chemical pesticides used in agriculture kill not only weeds, fungi and harmful insects but also honeybees, bumblebees, butterflies and other insects and the birds that live on them. The demand for profitability imposed by our society has made a mess of things for ourselves and for many other creatures, including bees.

But there are opposing forces. As a result of books like Maja Lundes The History of Bees