This book is dedicated to the first wild mammal I sawa Small Indian mongoose in my garden. He didnt mind me, and it all started from there.

Contents

During the COVID-19 lockdown, I turned to the sky.

MarchAprilMayJuneJulyAugust 2020. The worst-known pandemic in recent history, and the confinement of billions of people. As a virus, a tiny force of nature, shut us indoors, the wild brushed against my cheeks. In March, the Semal tree dropped its red flowers, and the Palash tree, also known as the Flame of the Forest, burst into orange bloom. A single stolen glance at the Palash, sizzling like a GIF on the central median of a busy Delhi street, was all I could see of it in 2020. That sight of a jungle tree in Delhi, which comes into blossom once a yearone I would normally travel to Central Indian forests to witnesswill be preserved in my heart forever.

In May, the Neem tree outside my window exploded into a universe of tiny, star-like flowers. Pioneer butterflieswith wings in various shades of cream and beigealighted on flowers of the same colour. Through the five-inch gap between the grills of my kitchen window, I saw scores of butterflies each day, emerging merrily at about 9 a.m., as soon as the sun warmed the Neem leaves. In June, the same tree nodded with green-gold fruit, and as the fruit turned from bitter to sweet, I was fortunate to spy a family of Yellow-footed green pigeons grow up on the tree. Like the off-white Pioneer butterflies that were poised on the milky Neem flowers in May, the downy green pigeon chicks with pale yellow feet were of the same colour as the Neem leaves and fruits in June. And then, there was the sky. It was blue. It was not the dull grey of the pre-lockdown sky, usually fogged over with fumes. This sky was unencumbered by vehicle emissions. Through the sky, and the trees touching the sky, the amorphous days of the lockdown assumed shape and meaning. And magic.

During the same lockdown period, an oil well blew up near Dibru-Saikhowa National Park in Assam, which is home to some of Indias most restricted species, such as the Bengal florican, the White-winged wood duck and, possibly, the White-bellied heron. The Indian government tried to weaken its Environment Impact Assessment laws. Locusts from Arabian deserts or Africa came whirring through to western and northern India, stopping for a few tumultuous days in Delhi.

This book is about the wild that walks alongside us and through the pages of our neat, daily lives. I have been to deserts, mountains, rivers, woodlands, lakes and political capitals to bring you the stories of Indias wildest citizens, along with some remarkable people who share insights on, and their lives with, these animals.

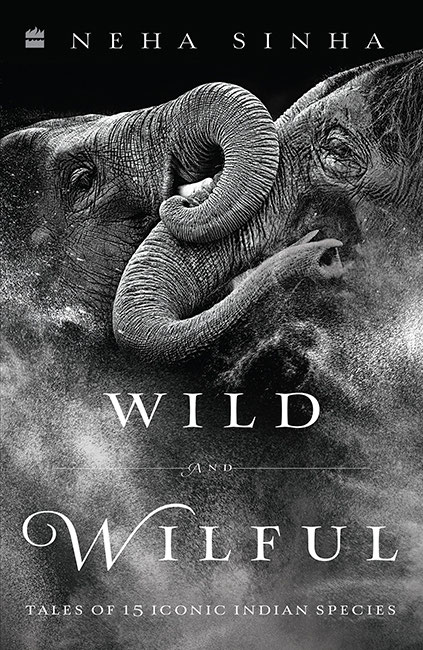

We look at iconic species found in India: The Indian Leopard, the Asian elephant, the Bengal Tiger, the Great Indian Bustard, the White-bellied heron, the Amur falcon, the Ganges river dolphin, the King cobra and the Spectacled cobra, Tiger butterflies, Rhesus macaque monkeys, the Rosy starlings and the magarmach or the Mugger crocodile.

I have taken a leaf out of the book of my favourite environmental superhero, Captain Planet, who was made of five elements: Earth, Sky, Water and Heart. The last element is perhaps the most important, as we can have no hope of reconciliation with our place and limitations in the world without applying our heart.

Thus, the book loosely follows the structure of Earth, Sky, Water and Heart.

It is divided further into the places where the animals are found. Under Land, we have political capitals, deserts, woodlands and forest. Under Sky, we have birds and butterflies that spend days migrating between countries or states. Under Water, we have ponds and rivers. Under Heart, we have urban jungles, the places many of us live in, and the places where we lose and find ourselves in repeatedly.

We start with the Leopard that lives in the political capitals of DelhiNCR and Dehradun. The Leopard is in deep trouble todaypersecuted, poached and trapped. It is targeted because it gets sighted, criminalized just for existing. Leopards cant easily be distinguished from each other. So, though there are candlelight marches for tigers like Ustad or Avni, who are easily recognizable as individuals, there are hardly any protests when leopards are persecuted. Yet, this resilient big cat tiptoes around hurdles through the land. It is so good at survival, we attribute it is in the wrong place, crossing the boundaries which we set for non-humans. When the leopard is found anywhere other than a marked wildlife reserve, it becomes a pest, a cockroach. The first chapter examines the leopard and the complexity of its existence in sub-Himalayan Dehradun and Delhi, and how letting the animal draw its own map is better than giving it a hotel-stay in a zoo.

We then move to Indias decision-making hub, the Parliament in Delhi, and the Rhesus macaque monkeys who often visit Parliament and other areas where decision-makers live. Monkeys are fed in temples and stoned outside them. They have learnt to open refrigerators, snatch things when they need to, and live amongst us. Today, they are at the centre of a furious culling debate. This chapter asks: Do we hate monkeys because they are too smart, or do we dislike them because they hold up a mirror to human behaviour?

From Delhis Parliament, we go to another kind of land, the marubhoomi or the deserts of India. Here we meet the Great Indian Bustard (GIB), named after India, but now reduced to a hundred-odd birds. The GIB has very specific habitat needsit requires dry, hot scrubland that we like to call wasteland. As the GIB collides with electric lines or succumbs to habitat loss, we must ask: Is the bird a fossil that time left behind, or are we too primitive to appreciate its specificities? Yet, the GIB may still rise like a phoenix from the ashes. We meet the first GIB chicks raised in captivity, and their foster mother.

All Indians know about the cobra, the reptile that winds itself around Lord Shivas neck in Indian mythology, the reptile that people both kill and worship. We meet Manjeet Kaur, a rare brand of intrepid woman, who rescues cobras in Chhattisgarh. We then move to sub-Himalayan regions in Uttarakhand to the King Cobra, which is not related to cobras, but would certainly eat one if it got a chance. From cameras in their eyes to gemstones in their heads, mythology and reality combine to create a cocktail of stories around the cobra and the king cobra. Some people kiss them, with devastating consequences. Others hunt them for their symbolism. Both species need attention for conservation and application of common sense from our side.

We then move to a giant of the Earth, the Asian elephant. Our national heritage animal is attacked by bombs lobbed at it in West Bengal, living alongside conflict, tail-pulling, and railway lines that kill in other parts of India. The scarred body of the Elephant, an exploring, migratory animal, is a monument of conflict. I tell the story of Laden, an Elephant seen as a thief and murderer in Assam, and the story of Ganga, a devoted mother to her calf as well as calves of other herd members in Bengal. Despite the challenges they face, elephants are slowly recolonizing their space and the monument of their bodies, negotiating the jigsaw of the landscape piece by piece, seeming to move back towards central India. There is hope that we can live without the death of man or beast if we doff the skin of the civilized human and think like an Elephant while planning the landscape.

Next page