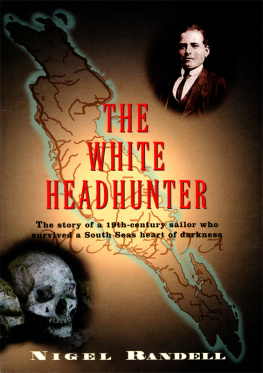

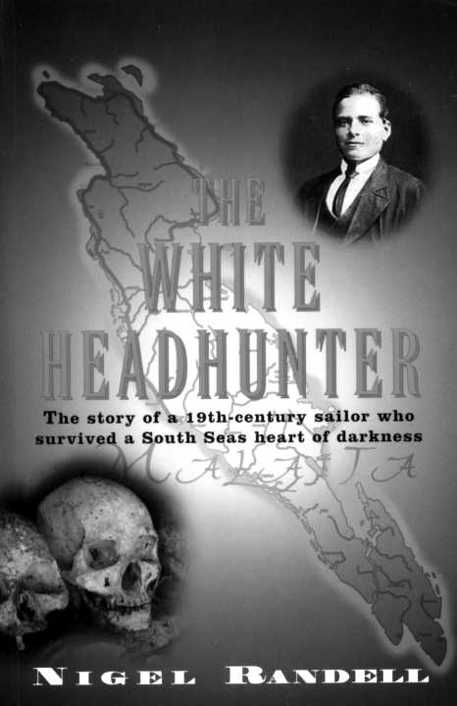

Necklace of 59 human teeth brought back by Jack Renton. A detailed description appears on pages 289-90.

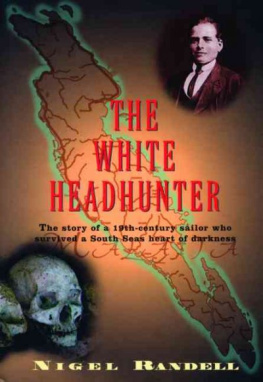

The WHITE HEADHUNTER

N I G E L R A N DE L L

Contents

vii

ix

xi

xv

Acknowledgements

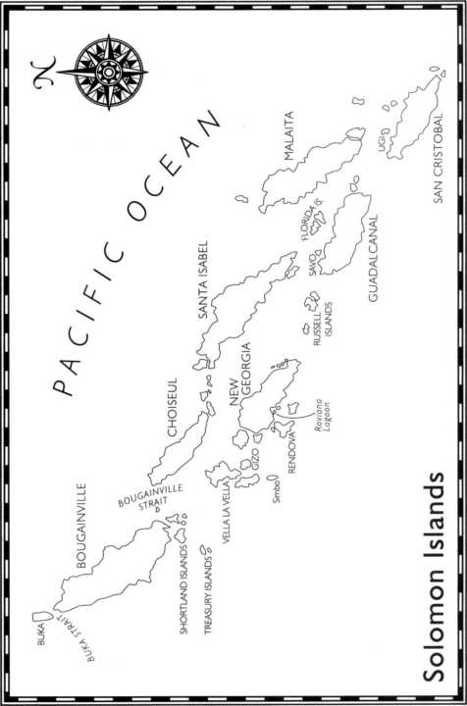

This story was slowly excavated on a number of visits over eight years, to a group of Pacific islands that see few tourists. The Solomon Islands, in particular, has been without government or infrastructure for over seven years and were it not for the hospitality of a number of people, Melanesians, missionaries and expatriates, my task would have been impossible. In particular I would like to thank Robertson Batu, Stewart Diudi, Ashley Kakaluae, Nathan Kera, Falataou Levi, Charlie Panakera, Dorothy and Loata Parkinson and finally, my long time guide and mentor, Tessa Fowler, for housing me, feeding me and often interpreting for me. I owe special thanks to my brother James who, over a number of years, looked after me in Sydney on my return from the islands and helped me with ordering the material - tapes, transcripts and photocopies that gradually leaked out of the guestroom to invade his house.

If this hook can lay any claim to being unique then it is entirely due to the contributions of oral historians in the Solomons and Vanuatu. In particular I would like to thank Nelson Jack Boe, Anathanasias Orudiana, Jacob Selo, Grace Sosoe, Malachi Tate, Stewart Diudi, Peter Afoa and John Tamanta. I am particularly grateful to Mike McCoy who undertook the initial interviews.

During the years of research and writing there are a number of people in England and Australia whose help, encouragement and advice I would like to put on record. So my thanks to Dr Ian Byford, Andrew and Wendy Evans, Richard Gihh, Sara Feilden, Clare Littleton, Niall McDevitt, Ron Parkinson, Ben Timberlake, Dr James Warner, Chris Wright and, in particular, Genna Gifford.

For their courtesy and patience I owe a particular debt of thanks to Lawrence Foauna'ota of the Solomon Islands National Museum, the staff of the Western Solomons Cultural Centre, Kirk Huffman of the Vanuatu Cultural Centre, Wendy Morrow of the National Library of Australia, and finally, the staff of the Mitchell Library in Sydney.

Like many first-time authors who know little about publishing, I was entirely dependent upon my agent for an introduction to this world. So to Andrew Lownie I owe a debt of thanks for his guidance, perseverance and enthusiasm and as all authors need an experienced editor, I believe that I was particularly fortunate. With candour, kindness and a sense of humour, Carol O'Brien shepherded me through all the hoops.

List of Illustrations

Jack Renton

Courtesy of The Mitchell Library, Sydney

Renton fishes for a shark

Courtesy of The Mitchell Library, Sydney

Recruiting, Panchumu Mallicolo

Courtesy of The National Library of Australia, Canberra

SUIUfou*

The newly recruited on their way to Queensland

Courtesy of The National Library of Australia, Canberra

Recruiters and boat crew, New Hebrides

Courtesy of The National Library of Australia, Canberra

Kwaisulia of Ada Gege

Ancestral head

Royal Anthropological Institute

Kanaka labourers arriving at Bunderburg

Courtesy of The National Library of Australia, Canberra

Levuka Harbour, Fiji, 1881

Courtesy of The Mary Evans Picture Library

Cutting sugar cane on a Queensland plantation, 1883

Courtesy of The Mitchell Library, Sydney

Santa Isabel tree house

`The Western Pacific', Walter Coote, 1883

Ingava of Roviana lagoon

`Man' Magazine Vol 14. 1907

Nuzu Nuzu

Royal Geographical Society

War canoes in full cry

`The Savage South Seas', Elkington, 1897

A fully manned war canoe from Roviana

The Royal Geographic Society

HMS Royalist bombarding Ingava's headquarters, 1891

Courtesy of The Mary Evans Picture Library

Jock Cromer's recruiting ship, Fearless

Courtesy of The National Library of Australia, Canberra

Skulls - A hush reliquary *

*All Nigel Randell

The necklace is reproduced on page i by kind permission of the National Museums of Scotland.

Introduction

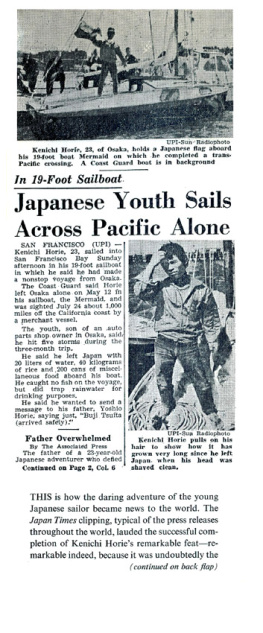

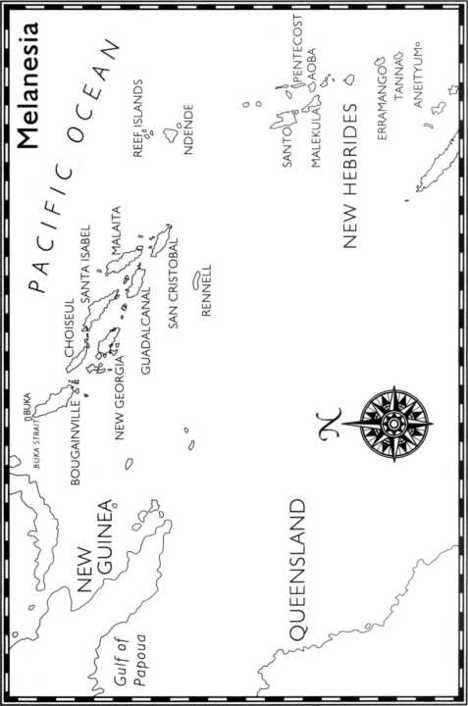

'HE South Pacific, as a real place, had almost disappeared. For two centuries this vast expanse of ocean and its thousands of little islands formed the backdrop upon which was projected all the baggage of European wish-fulfilment. It was not the writings of Banks, Bougainville, Cook or Rousseau, beguiling though they were, that touched an escapist chord in nineteenthcentury Britain, but a literary genre that held enormous appeal for the newly literate masses contemplating their baleful futures in the Industrial Age. The 'Beachcomber Memoirs' were true stories of ordinary seamen who had reinvented themselves on an alien shore. Men (and it was always men) who, by accident or design, had chosen a different life.

'HE South Pacific, as a real place, had almost disappeared. For two centuries this vast expanse of ocean and its thousands of little islands formed the backdrop upon which was projected all the baggage of European wish-fulfilment. It was not the writings of Banks, Bougainville, Cook or Rousseau, beguiling though they were, that touched an escapist chord in nineteenthcentury Britain, but a literary genre that held enormous appeal for the newly literate masses contemplating their baleful futures in the Industrial Age. The 'Beachcomber Memoirs' were true stories of ordinary seamen who had reinvented themselves on an alien shore. Men (and it was always men) who, by accident or design, had chosen a different life.

Throughout the century a stream of books, articles and serializations flooded the market on both sides of the Atlantic - ten such books in English were published between 1831 and 1847 alone. Many are remarkable, not least because they capture, even in the rough ethnocentric prose in which most are written, a moment in time - the genuine, unrepeatable moment of fear and wonder when, both black and white, floundering across a chasm of disbelief, struggled to acknowledge their common humanity. For the `visited', without the conceptual tools to deal with the unknown, this must have been an epiphany - nothing would ever be the same again. Unlike the discoveries of Galileo, Newton or Darwin and the gradual dawning upon Europe's intelligentsia of a different worldview, these visitations would have been earth shattering.

'HE South Pacific, as a real place, had almost disappeared. For two centuries this vast expanse of ocean and its thousands of little islands formed the backdrop upon which was projected all the baggage of European wish-fulfilment. It was not the writings of Banks, Bougainville, Cook or Rousseau, beguiling though they were, that touched an escapist chord in nineteenthcentury Britain, but a literary genre that held enormous appeal for the newly literate masses contemplating their baleful futures in the Industrial Age. The 'Beachcomber Memoirs' were true stories of ordinary seamen who had reinvented themselves on an alien shore. Men (and it was always men) who, by accident or design, had chosen a different life.

'HE South Pacific, as a real place, had almost disappeared. For two centuries this vast expanse of ocean and its thousands of little islands formed the backdrop upon which was projected all the baggage of European wish-fulfilment. It was not the writings of Banks, Bougainville, Cook or Rousseau, beguiling though they were, that touched an escapist chord in nineteenthcentury Britain, but a literary genre that held enormous appeal for the newly literate masses contemplating their baleful futures in the Industrial Age. The 'Beachcomber Memoirs' were true stories of ordinary seamen who had reinvented themselves on an alien shore. Men (and it was always men) who, by accident or design, had chosen a different life.