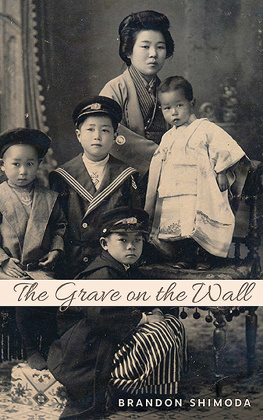

Here we learn that to attempt to recuperate an erased past is an obsessive task, following faint threads into places of memorial, tragic time, aging bodiesthe fissures, gaps, and scars of which can never be fulfilled. In the void between, ghosts emerge and disappear as dreams. A photograph on a wall in an obscure museum in an old Montana fort of layered imprisonments becomes our ghost-guide, its playful enigmatic gaze the journeys beginning. In a weaving meditation, Brandon Shimoda pens an elegant eulogy for his grandfather Midori, yet also for the living, we who survive on the margins of graveyards and rituals of our own making.

Karen Tei Yamashita, author of Letters to Memory

If someone asked me what a poets history might look and read like, I would say Brandon Shimodas The Grave on the Wall. It is part dream, part memory, part forgetting, part identity. It is a remarkable exploration of how citizenship is forged by the brutal US imperial forcesthrough slave labor, forced detention, indiscriminate bombing, historical amnesia and wall. If someone asked me, where are you from? I would answer, from The Grave on the Wall.

Don Mee Choi, author of Hardly War

In The Grave on the Wall, Brandon Shimoda has conceived a moving monument to his grandfather Midori made not of stone but of fractured memories and dreams, fairy tales and family photographs, pilgrimages to alien enemy internment camps, burial grounds, deserts, and the Inland Sea, all bound together by lambent strands of ancestral and immigrant histories. Within this haunted sepulcher built out of silence, loss, and griefits walls shadowed by the traumas of racial oppression and violencea green river lined with peach trees flows beneath a bridge that leads back to the grandson. To read this astounding grave on the wall, to peel back the walls layers of meaning, reveals less a finished portrait of the man made of ash than a rippling representation of the related forces at play that shape the grandfathers absence.

Jeffrey Yang, author of Hey, Marfa: Poems

In The Grave on the Wall, Brandon Shimoda pays tribute to the grandfather he never knew, and so for the rest of us, attends to that untold debt we all owe our forebears to whom we owe, if not the ordinary dailiness of lives, then at least basic facts of our existence. The legacy of past generationsthough we embody them in some way, so often unknowingly replicate their gestures, tones of voices or facial expressions, maybe the curl of a lock of hairthat inheritance so often goes untold, except that Brandon Shimoda begins here accounting for it, beyond the borders of memory and forgetting, beyond the known and unknown. Shimoda intercedes into the absences, gaps and interstices of the present and delves the presence of mystery. This mystery is part of each of us. Shimoda outlines that mystery in silence and silhouette, in objects left behind at site-specific travels to Japan and in the disparate facts of his grandpas FBI file. Gratitude to Brandon Shimoda for taking on the mystery which only literature accepts as the basic challenge.

Sesshu Foster, author of City of the Future

Brandon Shimodas The Grave on the Wall begins with a sentence that cannot be read. Impossible writing: My grandfather had one memory of his childhood in Hiroshima: washing the feet of his grandfathers corpse. This is a book that cant be repaired or remembered, but which conjoins itself to sub-luminous modes of loss in possible readers. Shimoda is a mystic writer. He puts what breaches itself (always) onto the page, so that the act of writing becomes akin to paper-making: an attention to fibers, coagulation, texture and the water-fire mixtures that signal irreversible alteration or change. Does this book end? Is there a sentence that closes it? Or does it keep being written and forgotten then written again, each time a reader opens it (the book) for the first time? I have never met this writer in person, and perhaps I never will, but he has written a book that touches the bottom of my own soul.

Bhanu Kapil, author of Ban en Banlieue

Sometimes a work of art functions as a dream. At other times, a work of art functions as a conscience. In the tradition of Juan Rulfos Pedro Pramo, Brandon Shimodas The Grave on the Wall is both. It is also the type of fragmented reckoning only America could instigate.

Myriam Gurba, author of Mean

THE GRAVE ON THE WALL

Brandon Shimoda

City Lights Books | San Francisco

City Lights Books | San Francisco

Copyright 2019 by Brandon Shimoda

All Rights Reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Shimoda, Brandon, author.

Title: The grave on the wall / Brandon Shimoda.

Description: San Francisco : City Lights Books, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019015708 (print) | LCCN 2019020566 (ebook) | ISBN 9780872867932 | ISBN 9780872867901 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Shimoda, Midori 1911-1996. | Shimoda, BrandonFamily. | Japanese AmericansBiography. | Japanese American photographersBiography. | ImmigrantsUnited StatesBiography. | Japanese AmericansEvacuation and relocation, 1942-1945. | Grandfathers. | Grandparent and child.

Classification: LCC E184.J3 (ebook) | LCC E184.J3 S47 2019 (print) | DDC 973/.04956dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019015708

City Lights Books are published at the City Lights Bookstore 261 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94133

www.citylights.com

for my great-great-grandmother, Yumi Taguchi

and my daughter, Yumi Taguchi

Subject stated he thinks Japan is Hell. Subject stated, I dont want to go back to Japan and I wish that they would give me a gun to go and fight Japan.

Subjects appearance is due to possession of camera. He is physically frail, of an artistic and very sensitive nature. He is high strung. He had difficulty restraining tears. He feels discouraged. He came to America when he was nine. He states it is difficult for him to look at himself as an alien... Certainly none of his conduct bears a remote relation to anything subversive... He represents one of the many individual tragedies of the war... We recommend that he is paroled under sponsorship as soon as possible so that his spirit may not be broken.

As a result of my contacts with this man, I am convinced that he has a plan in mind to do something which may be harmful to the country or the people in it and have been thoroughly satisfied to have him interned, and for that reason I do not believe that he should be allowed on his own until we know more about what was impelling his wilful [sic] violation of orders.

1128762

THE PERIOD OF SUMMONING RELATIVES

My grandfather had one memory of his childhood in Hiroshima: washing the feet of his grandfathers corpse. He was six or five or four. He stood in the doorway of the room where his grandfathers corpse had been prepared. His grandfather, covered in a white towel and lying on a thin futon in the middle of the room, looked like he was sleeping. There was a sponge in a large white bowl of lucid water, and a robe, tightly folded, in the corner. My grandfathers mother and three older brothers nodded at him to enter.

He looks like he is dreaming.

He studied his mother and brothers before kneeling beside them. He touched one of his grandfathers feet. The first touch was the most daunting. The vein. He was afraid it might come apart in his hand. The skin was the texture of the rooms in which he spent time with his grandfather. But the seasons had been extinguished. He sank the sponge in the water, wrung it out, and touched it, tentatively, to his grandfathers sole.

Next page

City Lights Books | San Francisco

City Lights Books | San Francisco