This edition is published by ESCHENBURG PRESS www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books eschenburgpress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1944 under the same title.

Eschenburg Press 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

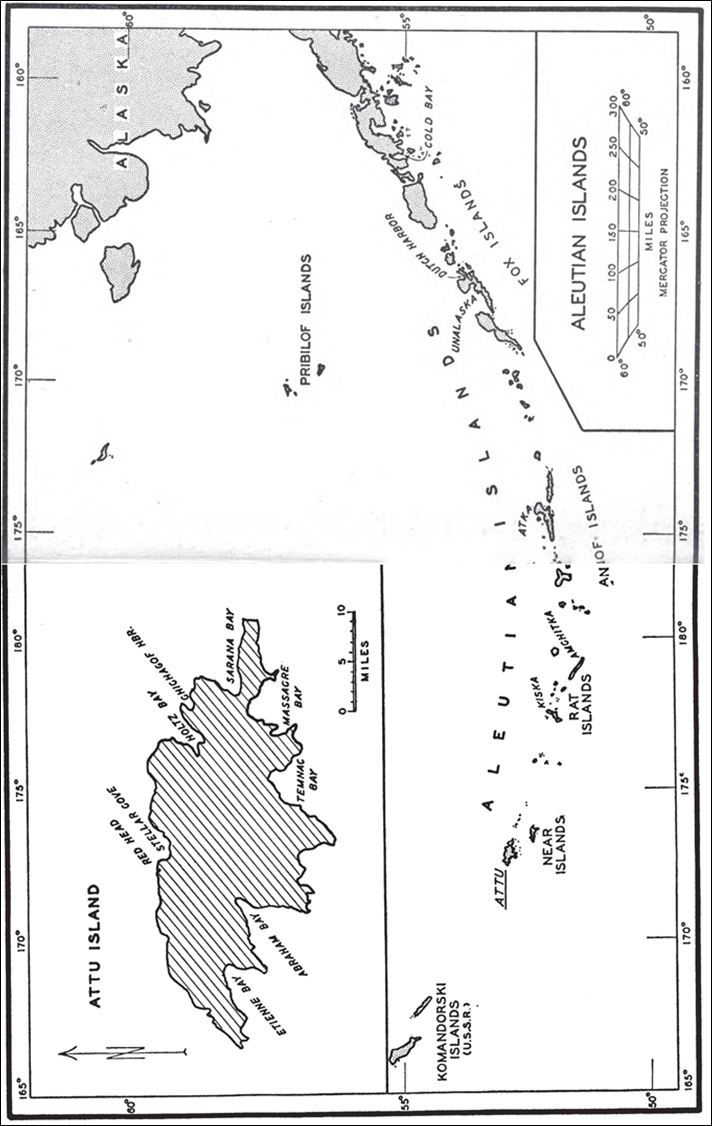

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

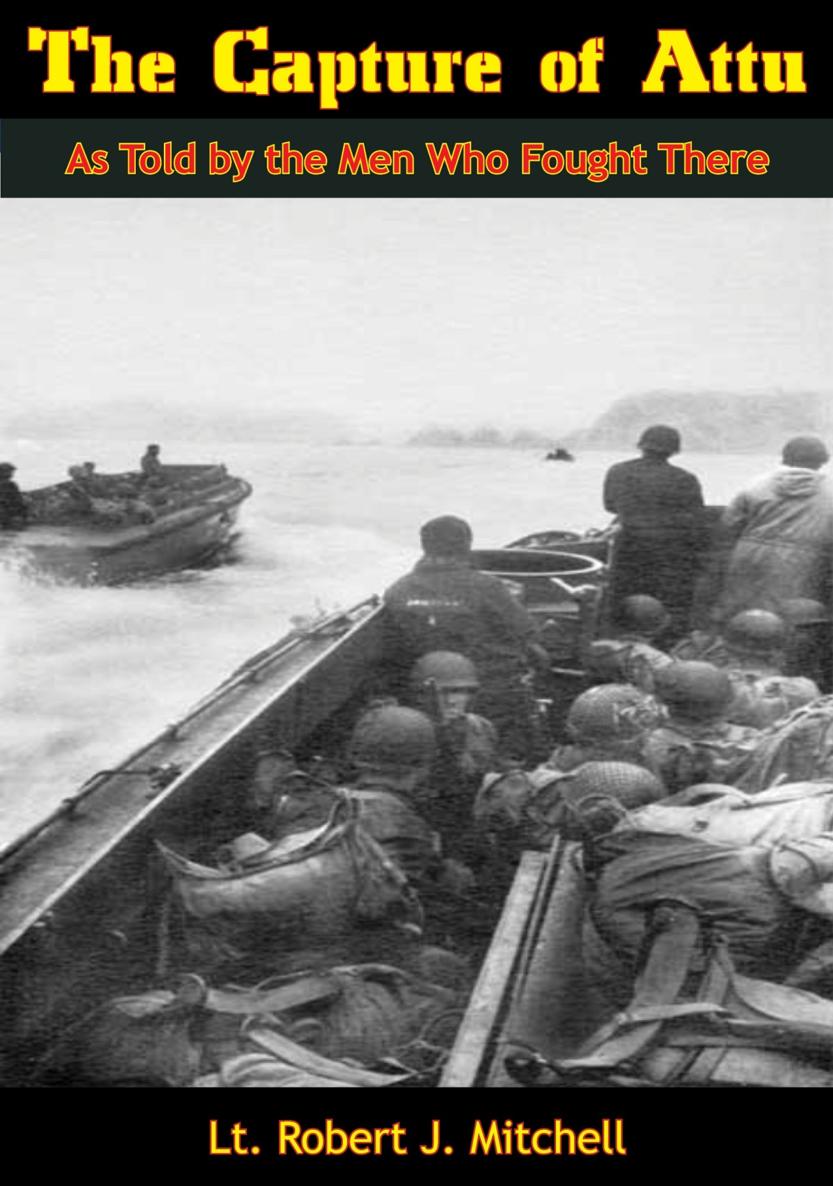

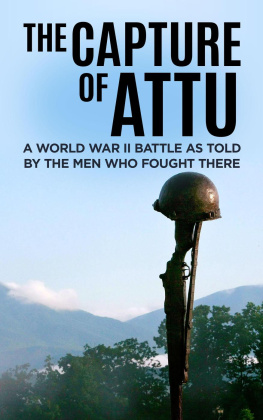

THE CAPTURE OF ATTU

AS TOLD BY THE MEN WHO FOUGHT THERE

PREPARED BY

THE WAR DEPARTMENT

PREFACE

This book attempts to put the reader on the battlefield with the ground soldier. Men who fought on Attu, officers and enlisted men, told their stories to Lieutenant Robert J. Mitchell of the 32 nd Infantry, one of the regiments engaged. Lieutenant Mitchell was wounded during the latter stage of the battle and while convalescing wrote the accounts which are now published as Part Two of the book. These stories tell of the discomforts and perils, the failures and successes, the fear and courage, the many fights between small groups and the occasional humor, of which battle consists. In preparing these accounts for publication, every effort has been made to keep them as nearly as possible in the exact form in which they were written down by Lieutenant Mitchell; consequently, a minimum of editorial changes has been made.

Part One, written by Sewell T. Tyng, is an introduction in the form of a connected narrative of events leading up to the invasion of the Aleutian island of Attu and a detailed account of the battle which resulted in the capture of Attu by American forces. This narrative is based on official sources and on material collected by Captain Nelson L. Drummond, Jr., Field Artillery, formerly of the Alaska Defense Command. Captain Drummond visited Attu shortly after the battle, studied the terrain, and interviewed participants of all ranks.

The volume has been prepared in the War Department under the supervision of the Military Intelligence Division. Aerial photographs are by the 11 th Air Force; battle photographs are by the U.S. Army Signal Corps; and terrain feature photographs are by Captain Drummond, assisted by Private First Class A. E. Johnson, 50 th Engineer Regiment. The panoramic sketch is based on an original by the 50 th Engineer Regiment.

The publication of the volume in its present form has been made possible by the co-operation of Colonel Joseph I. Greene, Editor of The Infantry Journal , and his staff.

PART ONETHE BATTLE OF ATTU

The battle of Attu was essentially an infantry battle. The climate greatly limited the use of air power, for almost every day the island was shrouded in fog and swept by high winds. The terrainsteep jagged crags, knifelike ridges, boggy tundramade impracticable any extensive use of mechanized equipment and, indeed, of all motor vehicles. Thus deprived of the most important accessories of modern war, the Doughboy, moving only on foot, had to blast his way to victory with the weapons he could carry with him.

The job was far from easy. In fact it proved much harder than had been expected. For American troops that were inexperienced in combat, fighting under the toughest conditions, found themselves faced by a vigorous enemy, fully equipped, thoroughly acclimated, and fanatically determined to hold their strong, well-chosen defensive positions.

But the men who fought on Attu added a memorable page to the story of the United States Infantry.

THE ISLAND OF ATTU

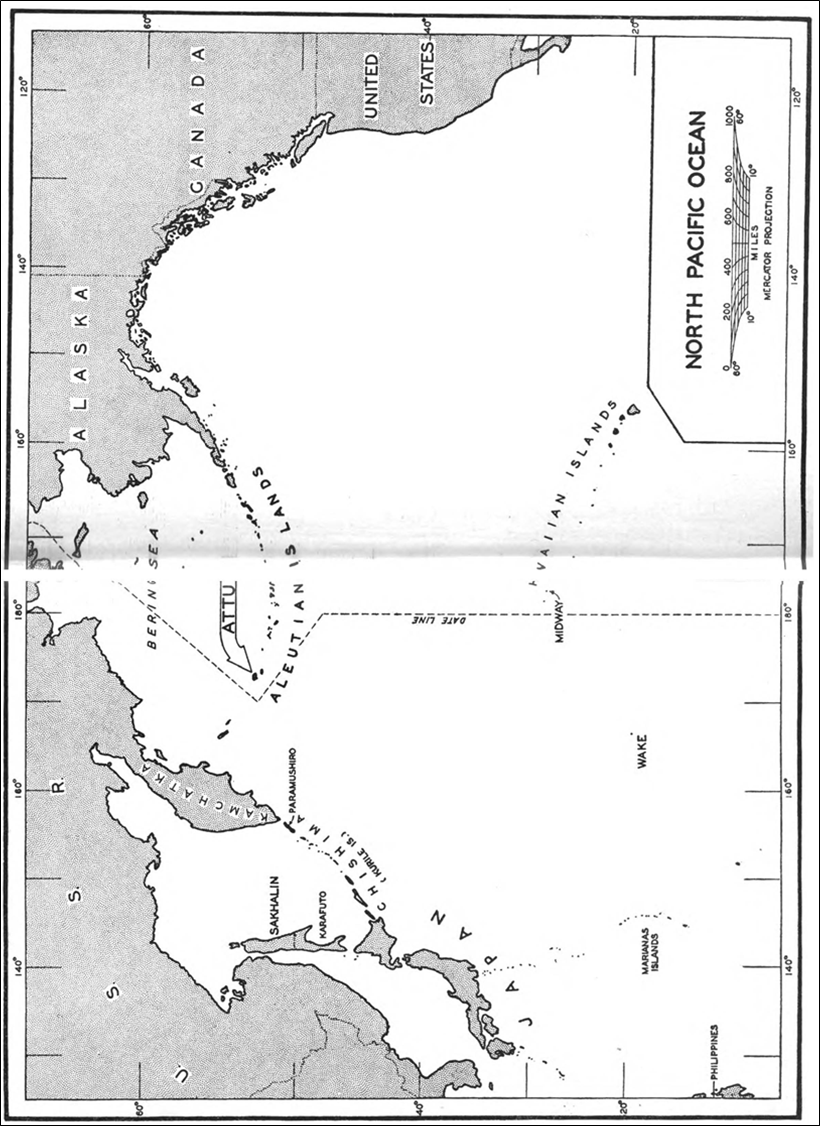

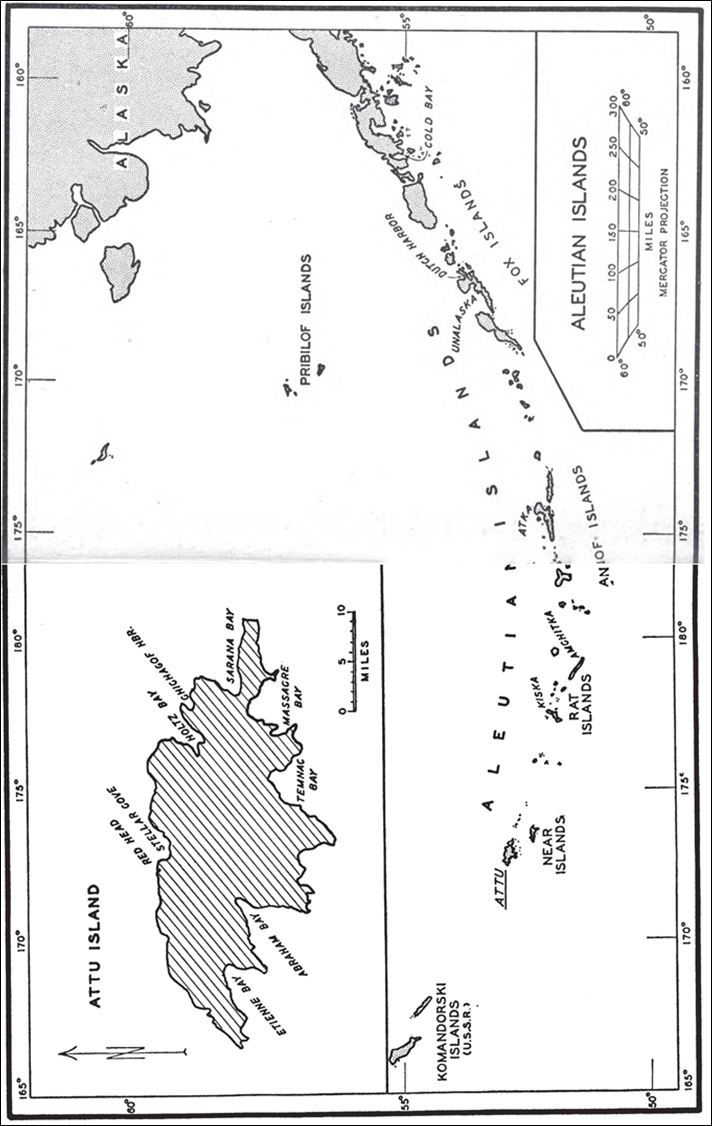

The Aleutian Islands, discovered in 1741 by Vitus Bering, a Danish navigator employed by Russia, were acquired by the United States in 1867 as a part of the Alaska Purchase. Extending for more than 1,000 miles westward from the Alaskan mainland, the chain ends with Attu, which is some 600 miles from Siberia and 650 miles from the Japanese base at Paramushiro in the Kurile Islands, the most northerly bastion of the main defenses of Japan.

Unsuited to agriculture, devoid of mineral resources, and with no other possibility of commercial exploitation, Attu received slight attention from the United States after its acquisition. However, a chart of the coast line was prepared by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, and a stock of blue foxes was placed on the island to provide its native inhabitants with a means of livelihood.

At the time of the Japanese occupation in June 1942 the population of the island consisted of forty-five native Aleuts, a branch of the Eskimos, and two Americans: Foster Jones, a sixty-year-old schoolteacher, and his wife. All lived in a little hamlet of frame houses around Chichagof Harbor, maintaining a precarious existence by fishing, trapping foxes, and weaving baskets. Occasional visits from missionaries, explorers, government patrol boats, and small fishing craft provided the inhabitants with their only direct contact with the outside world, except for a small radio operated by Mr. Jones. One writer has called Attu the lonesomest spot this side of hell.

Though the temperature on the island rarely attains arctic severity, Attu is beset through most of the year by a cold, damp fog, often accompanied by snow or icy rain. Even the high winds, which reach a velocity of more than 100 miles per hour, are not able to dispel the continuous fog. Fine days on Attu are rare indeed, and there are many days when the weather prevents any possibility of outside work.

Only a short distance from the shore line and throughout the interior of the island, steep mountains rise abruptly to a height of some 3,000 feetrugged peaks and narrow, knife-sharp ridges without growth, usually covered with snow. The valleys and the lower slopes are covered by a layer of tundra, muskeg-like moss and coarse grass, which gives an elastic quality to the ground. Water seeps under this layer. Even a man on foot may readily break through the tundra, sinking in watery mud up to his knees. Motor vehicles, even those with caterpillar treads, quickly chum the tundra into a muddy mass in which sunken wheels and treads spin uselessly.

During the seventy-five years prior to the Japanese occupation, while Attu belonged to the United States, no agency of the government made any detailed survey of the topography of the interior of the island and no military installations of any kind existed on it. Until the development of long-range aircraft Attu had little strategical importance and thereafter limitations on funds and personnel made it necessary to concentrate military expenditures on other more vital areas. Consequently at the time of the American attack in the spring of 1943 only the shore line was accurately mapped. No accurate maps existed of the mountains and passes over which the American forces had to fight.