The Capture of Attu

Robert J. Mitchell et al.

Published by Ship to Shore, 2018.

Copyright

The Capture of Attu: A World War II Battle as Told by the Men Who Fought There by Robert J. Mitchell, Sewell T. Tyng and Nelson L. Drummond. First published in 1944.

Annotated edition Copyright 2018 by Ship to Shore Books.

All rights reserved.

Published by Ship to Shore Books, Los Angeles.

ISBN: 978-0-359-13951-4.

Part One

The Battle of Attu

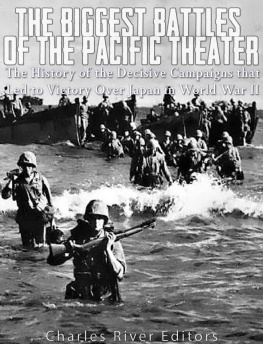

Image: American troops unload supplies on the shores of Attu.

T HE BATTLE OF ATTU was essentially an infantry battle. The climate greatly limited the use of air power, for almost every day the island was shrouded in fog and swept by high winds. The terrain - steep jagged crags, knifelike ridges, boggy tundra - made impracticable any extensive use of mechanized equipment and, indeed, of all motor vehicles. Thus deprived of the most important accessories of modern war, the Doughboy, moving only on foot, had to blast his way to victory with the weapons he could carry with him.

The job was far from easy. In fact it proved much harder than had been expected. For American troops that were inexperienced in combat, fighting under the toughest conditions, found themselves faced by a vigorous enemy, fully equipped, thoroughly acclimated, and fanatically determined to hold their strong, well-chosen defensive positions.

But the men who fought on Attu added a memorable page to the story of the United States Infantry.

The Island of Attu

T HE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS , discovered in 1741 by Vitus Bering, a Danish navigator employed by Russia, were acquired by the United States in 1867 as a part of the Alaska Purchase. Extending for more than 1,000 miles westward from the Alaskan mainland, the chain ends with Attu, which is some 600 miles from Siberia and 650 miles from the Japanese base at Paramushiro in the Kurile Islands, the most northerly bastion of the main defenses of Japan.

Unsuited to agriculture, devoid of mineral resources, and with no other possibility of commercial exploitation, Attu received slight attention from the United States after its acquisition. However, a chart of the coastline was prepared by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, and a stock of blue foxes was placed on the island to provide its native inhabitants with a means of livelihood.

At the time of the Japanese occupation in June 1942, the population of the island consisted of forty-five native Aleuts, a branch of the Eskimos, and two Americans: Foster Jones, a sixty-year-old schoolteacher, and his wife. All lived in a little hamlet of frame houses around Chichagof Harbor, maintaining a precarious existence by fishing, trapping foxes, and weaving baskets.

Occasional visits from missionaries, explorers, government patrol boats, and small fishing craft provided the inhabitants with their only direct contact with the outside world, except for a small radio operated by Mr. Jones. One writer has called Attu the lonesomest spot this side of hell.

Though the temperature on the island rarely attains arctic severity, Attu is beset through most of the year by a cold, damp fog, often accompanied by snow or icy rain. Even the high winds, which reach a velocity of more than 100 miles per hour, are not able to dispel the continuous fog. Fine days on Attu are rare indeed, and there are many days when the weather prevents any possibility of outside work.

Only a short distance from the shoreline and throughout the interior of the island, steep mountains rise abruptly to a height of some 3,000 feetrugged peaks and narrow, knife-sharp ridges without growth, usually covered with snow. The valleys and the lower slopes are covered by a layer of tundra, muskeg-like moss and coarse grass, which gives an elastic quality to the ground. Water seeps under this layer. Even a man on foot may readily break through the tundra, sinking in watery mud up to his knees. Motor vehicles, even those with caterpillar treads, quickly churn the tundra into a muddy mass in which sunken wheels and treads spin uselessly.

During the seventy-five years prior to the Japanese occupation, while Attu belonged to the United States, no agency of the government made any detailed survey of the topography of the interior of the island and no military installations of any kind existed on it. Until the development of long-range aircraft, Attu had little strategical importance and thereafter limitations on funds and personnel made it necessary to concentrate military expenditures on other more vital areas. Consequently at the time of the American attack in the spring of 1943 only the shoreline was accurately mapped. No accurate maps existed of the mountains and passes over which the American forces had to fight.

The Japanese Take Attu

O N JUNE 3, 1942, JAPANESE carrier-borne aircraft bombed American installations at Dutch Harbor on the island of Unalaska, causing a few casualties and minor damage, but not seriously impairing the military value of the base.

A few days later, Japanese troops landed on the islands of Kiska and Attu to the west. On Kiska they captured a small American naval detachment, a lieutenant and ten men. On Attu, which was not occupied by American armed forces, the elderly American schoolteacher committed suicide and his wife attempted to do the same. She recovered, however, under Japanese care, and, together with the entire Aleut population of the little village of Chichagof, was transported for internment to Hokkaido, Japan. The Japanese garrison had the island entirely to themselves.

Following image: Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, head of the Japanese Navy.

I N THE SEIZURE OF ATTU and Kiska* the Japanese had a three-fold objective as stated by Lieutenant General Hideichiro Higuda, commander of the Japanese Northern Army. They wanted to break up any offensive action the Americans might contemplate against Japan by way of the Aleutians, to set up a barrier between the United States and Russia in the event that Russia determined to join the United States in its war against Japan, and to make preparations through the construction of advance airbases for future offensive action. The Japanese High Command undoubtedly regarded the Aleutians as stepping stones to the North American mainland and ultimately to the continental United States itself.