Copyright 2021 by Candace OConnor

Published by the University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65211

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved. First printing, 2021.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: OConnor, Candace, author.

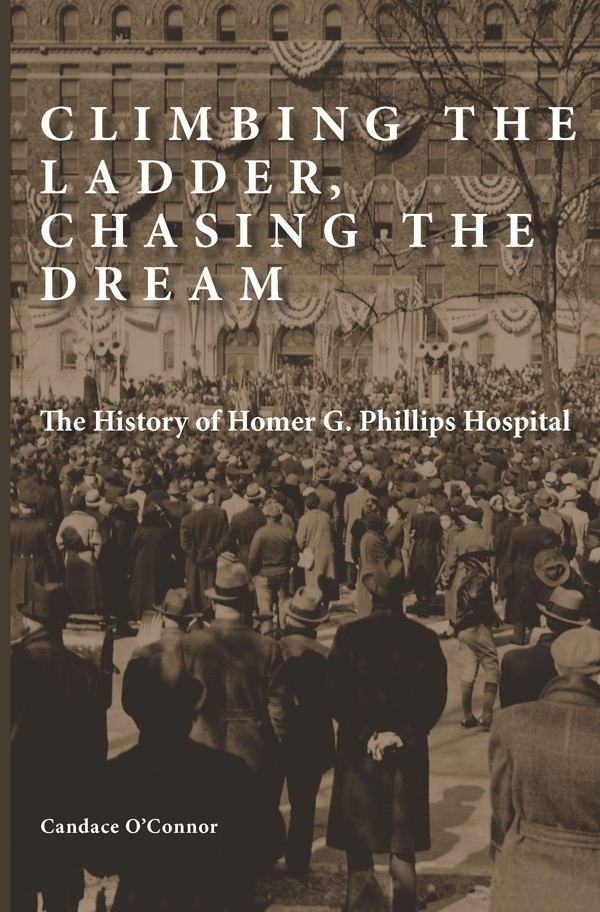

Title: Climbing the ladder, chasing the dream : the history of Homer G. Phillips Hospital / Candace OConnor.

Description: Columbia : University of Missouri Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021026146 (print) | LCCN 2021026147 (ebook) | ISBN 9780826222473 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780826274656 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Homer G. Phillips Hospital--History. | Hospitals--History--St. Louis, Missouri--1937 -1979 | Minorities--Medical care. | African Americans--Medical care. | Discrimination in medical care.

Classification: LCC RA964 .O26 2021 (print) | LCC RA964 (ebook) | DDC 362.1109778/66--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021026146

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021026147

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Typeface: Sabon

FOREWORD

Eva L. Frazer, MD

WHEN HOMER G. PHILLIPS HOSPITAL (HGPH) opened in 1937, legalized segregation meant, in virtually all instances, inferior treatment and fewer opportunities for Black patients and physicians. In response to these injustices, the vision of attorney Homer G. Phillipsand others who worked passionately with himled to the establishment of a nationally renowned hospital dedicated to the care of Black patients and the training of Black healthcare professionals. The tale of HGPH is particularly inspiring when contrasted with the Dred Scott decision of 1857 and the East St. Louis, Illinois, race riots of 1917, two historic events that had set a negative tone for race relations in the St. Louis region. This new history of the hospital is an uplifting and riveting narrative that includes an unsolved murder; an accidental electrocution; romance and war; and, during a time known for racial strife, an example of Black and white healthcare and civic leaders working together. It has all the makings of a historic biopic, spanning the Great Migration of Blacks from the South to the North, World War II, the civil rights movement, and the Vietnam War. Ironically, it was the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that led to the decline and ultimate closure of this esteemed hospital.

Noteworthy American stories feature men and women of integrity who overcome obstacles through hard work and perseverance. The history of Homer G. Phillips Hospital, named for the Black attorney who lobbied for its founding, is an outstanding example of such a story that has never before been fully recounted. This book takes on that challenge, integrating personal narratives with extensive research, bringing to life the institution and the people fundamental to its success.

As the daughter of an HGPH-trained surgeon and family practitioner, I lived in an East St. Louis neighborhood that included the homes, families, and offices of other HGPH graduates. My fathers closest friends and colleagues were all connected to what was then the mecca of training programs for Black physicians. My pediatrician, dentist, and every other doctor who treated me or my family was an HGPH graduate and family friend. My mother belonged to womens social groups primarily made up of the wives of these physicians.

These men and women had risen to the highest level attainable by the descendants of slaves in the social circles of the Black and white communities. My childhood was one of privilege, freedom, and infinite possibility, which, as I look back, was extremely rare for a Black girl growing up during the volatile period of transition from segregation to legally mandated integration. I was molded by witnessing the character, diligence, and integrity of these physicians, who were also civil rights activists, war veterans, and esteemed leaders in the communities they served. As an adult, I would follow in my fathers footsteps, becoming a physician and, in 1984, completing my training at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesotaa mere 20 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. But the significance of HGPH was not limited to me, my community, or even the St. Louis region. The extraordinary importance of HGPH would reverberate nationwide since, by 1960, HGPH had trained more Black physicians and nurses than any other institution worldwide. These graduates provided medical care in towns and cities across the country, taking the same high standard of medical care and civic leadership to the communities where they settled.

In 1937, when the doors to HGPH finally opened to great fanfare, few academic institutions in the United States offered training slots for Black medical graduates. HGPH gained notoriety not only for its newly built, state-of-the-art facilities but also for the wide array of subspecialty training opportunities that evolved from its collaboration with the acclaimed Washington University. The white faculty of Washington University wouldin an unprecedented movework with the Black physicians and administrative staff of HGPH as partners rather than superiors. Together, they would work to ensure that the HGPH trainees had capabilities equal to their white peers. In addition, training for nurses and allied health professionals at HGPH created a community of Black healthcare workers united toward a common goal: providing the best care available to Black patients. Prior to HGPH, African Americans in St. Louis were treated in hospital basements, back rooms, or substandard facilities and under conditions in one instance decried publicly as not being fit for zoo animals. The lasting impact of the people who worked, trained, and became leaders in their respective fields and communities makes the history of HGPH one of the greatest American tales of success, perseverance, and social justice. By the time of its forced closing in 1979, HGPH had become a tangible symbol of racial pride and a legacy in a community and nation that otherwise remained mired in racial inequities.

My father, Charles R. Frazer Jr., M.D., almost always dressed in a suit and tie with freshly polished leather shoes, and he liked to wear a fedora hat. He once built a swing set in our backyard dressed in what was for him casual clothes: a crisp, freshly starched, collared plaid shirt with tan belted pants and brightly polished shoes. He never broke a sweat in the hot summer sun. He was always cool, calm, and collected, and he had a special talenthe took care of people. Doc, as his friends and patients called him, was the doctor whom other doctors came to for advice. He was a man of few words, each one precise and to the point. He worked long hours as a solo family practitioner and general surgeon in East St. Louis in the late 1940s until his death in 1994. In our home, next to his office, it was not unusual for people to come knocking on the door in the middle of the night for help after an accident, sudden illness, unexpected death, or trouble with the law. As a child, I watched my father stitch people up, and on occasion he would let me cut the sutures as he worked. Doc gave otherwise frightening and chaotic situations a sense of order and redress. He took charge when needed but had the wisdom and grace to know when to sit back calmly and listen, always giving what was needed at just the right moment. It was a skill I instinctively wanted to acquire, and over time I tied much of it to his being a doctor. That was what defined him; it was not what he did, it was who he

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.