Copyright 2017 by Liisa Kovala

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotation embodied in reviews.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kovala, Liisa, 1972

[Day soon dawns]

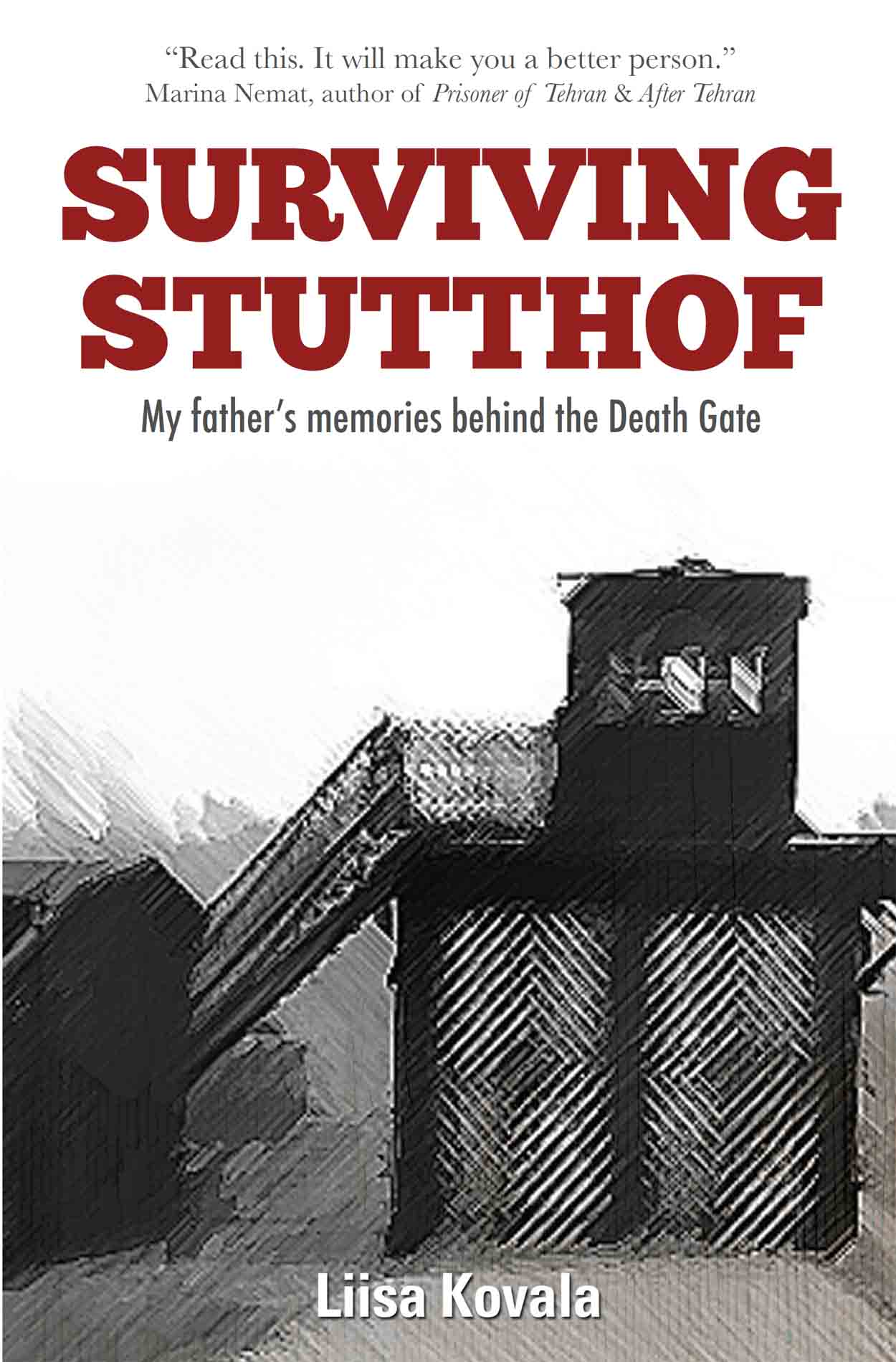

Surviving Stuttof : my fathers memories behind the death gate / Liisa Kovala.

Previously published as The day soon dawns : a Finnish sailors true story of surviving Stutthof: a family memoir. North Charleston, South Carolina: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, [2015]

ISBN 978-0-9949183-9-0 (paperback)

1. Kovala, Aarne. 2. Stutthof (Concentration camp). 3. Concentration camp inmates--Poland--Biography. 4. Prisoners of war--Finland--Biography. 5. Prisoners of war--Poland--Biography. I. Title. II. Title: Day soon dawns.

D805.5.S78K68 2017 940.5472430943822 C2016-907003-4

Book design: Christine Lewis

Cover Design: Christine Lewis

Author photo: Gerry Kingsley

Published by:

Latitude 46 Publishing

Latitude46publishing.com

For Is and iti

and

Mia and Kieran

Contents

Only guard yourself and guard your soul carefully, lest you forget the things your eyes saw, and lest these things depart your heart all the days of your life, and you shall make them known to your children, and to your childrens children.

Deuteronomy 4:9

Never, never, aged father,

Never, thou, beloved mother,

Never, ye, my kindred spirits,

Never harbour care, nor sorrow,

Never fall to bitter weeping,

Since thy child has gone to others,

To the distant home of strangers

Rune XXIV, The Kalevala

Aarne Kovala, 1941, age 13

Sudbury, 2012

Our journey together began on a cold Sunday afternoon in January, typical of Northern Ontario, on the first of what would be many weekly visits to my parents house in search of my fathers memories. The small brick bungalow was cozy and warm, although the temperature outside had plummeted. The picture window framed a view of the yard blanketed by a thick layer of snow, extending out to cover the ice on St. Charles Lake like a pristine sheet of paper. The sun bounced off the stark landscape and caught the light in the flecks blown from the rooftop. The familiar smell of coffee and fresh cardamom from my mothers homemade pulla, a traditional Finnish coffee bread, wafted in from the kitchen.

Since I was a child, Id heard fragments of my fathers story, but Id foolishly paid little attention. A natural storyteller, he was always conscious of his impressionable young listeners and avoided anything that might be too traumatic. Now, as an adult, I wanted to know what life had been like for my father in faraway Finland and Poland in the 1930s and 40s. As I prepared to write, I resolved not to let my fathers stories evaporate. I needed to preserve each droplet and join them with the river of memories that flow from witnesses around the world. I wanted to be able to tell my children and grandchildren what really happened, something more than partial recollections from childhood of dinnertime conversations.

After almost seventy years, he was ready to share his stories, and I was anxious to hear them. But how much would he remember? Was he ready to return to those dark times? Was I prepared to hear about the horrors?

Across from me, my eighty-three-year-old father, Aarne Kovala, sat in his faded blue armchair. He placed before me a white shoebox that I had coveted as a young girl. It smelled faintly of dust and mildew, but when I removed the lid, the images inside were as fresh and crisp as the day they were taken. I was astounded to find a collection of black and white photographs, postcards of ships, several passports, and seamens union cards, amongst other treasures. He had stuffed several decades of his life into this little container. Each piece represented a story, or could trigger a recollection. I knew if I asked the right questions the memories in the shoebox would come to life one by one.

My father had yet to speak. He sat in his chair, large forearms resting on his knees, back hunched forward in a posture so familiar to me. Between his thumb and forefinger, he aimlessly twisted and turned a piece of paper, as I had seen him do so many times before when he was lost in thought. His blue eyes, soft and kind, focused on something in the middle distance, the place between then and now, before he turned to look at me directly. The lines on his forehead furrowed as he shifted in his chair. Then, without warning, his eyes shone, and a smile animated his face.

He began to speak in the sing-song of his native Finnish, its long words and vowels rolling gently like waves. I looked at my mother, Anja, seated in her matching recliner. She shrugged slightly and shook her head. Were the memories of his Finnish past wrapped only in his native tongue? In that instant, I regretted never having learned my parents language.

When he finally paused, I said, OK, Dad. But youre going to have to tell me in English.

He started again.

His story began to flow, words tripping gently in his broken English, travelling to the river of his childhood, where he and his friends spent hours riding the rapids. From there, I knew, his words would bring us to the sea, to the ship that would carry him to the port that launched his nightmares. The ripples and waves of his story would, in time, uncover what lay beneath his calm exterior. It would also deliver him homebut not yet.

Instead, his story brought us to the beginning, to a small town in northern Finland and a young boy whose life was about to change forever.

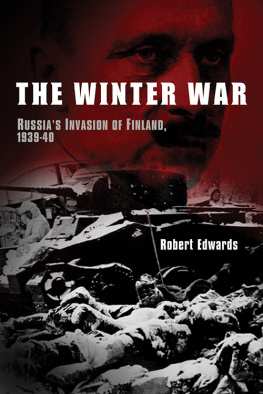

Oulu, January, 1940

The innocence of youth ended when bombs blasted Aarne Kovalas hometown. The raging rapids of the Oulujoki were silent under slabs of shifting ice, the lush gardens of Ainola Park were buried under quilts of white, and the warm sands of the Baltic lay barren while fire rained from the sky. It was the first day of the new decade.

Aarne, arms laden with firewood, followed his friend, Matti Salmi, up a set of narrow stairs, delivering fuel for the Salmis stove.

Aarne propped his chin on top of his load as he negotiated the steps.

Despite the icy temperatures outside, both boys were warm from exertion, their faces flushed and legs heavy.

They were almost at the top of the steps when they heard a distinctive brat-a-tat-tat, brat-a-tat-tat from somewhere in the distance. The boys froze and looked at each other with wide eyes. Machine gun fire. They dropped the kindling on the stairs and rushed to the little window overlooking the street.

The reverberations of low-flying plane engines echoed in the wooden stairwell, filling the small space with their oppressive sounds and causing the boys to catch their breath. Above, a Russian airplane, guns and gunners visible, cast a shadow on the street below, obstructing the view of the clear afternoon sky from the small window. The boys pressed their noses against the cold glass, clawing the window ledge as they surveyed the terrifying scene.

Aarne had overheard the adults discussing their worries about a war with Russia in the months preceding the fall of the first bombs. The Russians wanted to reclaim territory lost during the Russian Civil War. Back in 1917, Finland had declared its independence from Russia and now, over twenty years later, Stalin was demanding a portion of the land (along with islands in the Gulf) be ceded to Russia, arguing it was to protect Leningrad only forty kilometres away. Russia had already signed treaties of mutual assistance from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia and demanded more control over the Baltic. Finland, however, rejected Stalins proposals. War was inevitable.