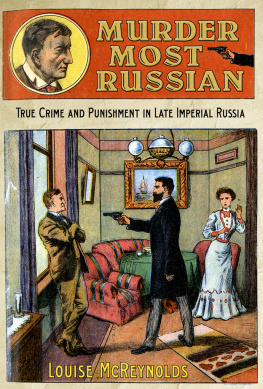

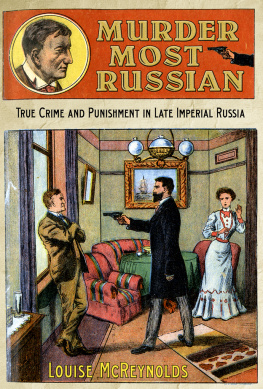

MURDER MOST RUSSIAN

TRUE CRIME AND PUNISHMENT IN LATE IMPERIAL RUSSIA

LOUISE McREYNOLDS

CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS

Ithaca & London

To my sister Betsy,

my best friend

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The debts that I have collected writing this book will be a pleasure to repay. Don Raleigh has always been there for me, critiquing the drafts in ways that improve my scholarship and sharing the easy with the hard times, life lived to its fullest. Joan Neuberger bounces around ideas and laughs that help to keep me sharp. In St. Petersburg, Tania Pavlenko and Tania Chernetskaia enrich my life more than they can imagine, and I appreciate conversations with Liuda Katenina, even though they must now be long distance. I am particularly beholden to the friends who took time from their own work to read and comment on mine: Marko Dumani, Robert Edelman, Beth Holmgren, Lynn Mally, Mark Steinberg, and Robert Weinberg. Though I remain responsible for the end product, their input made it a much better book. The line between colleague and friend is too narrow to be drawn, and I deeply appreciate the many ways that the following have been there for me: Boris Ananich, Laurie Bernstein, Steve Bittner, Pam Chew, Boris Kolonitskii, Dan Orlovsky, Ethan Pollock, Mark Sidell, Nancy Brave Solomon, and Bonnie Teel. My sister Rebecca was always so generous with her murder mysteries before she went digital, but we still share so much else. My sister Alice and I have enjoyed many a murder at the movies together. And I mourn the loss of those who began this project with me but departed before I could see it through: Alexander Fursenko, Janie Roden, Richard Stites, and Reggie Zelnik.

I am especially grateful for the institutional support that gave me the time to research and to write. I begin with the Fulbright-Hays Committee, which funded six months in Russia, and add the International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX), the Kennan Institute, and the University Research Council at the University of North Carolina, which provided for shorter trips. A year at the Institute for Advance Study at Princeton gave me the time to read through my copious materials, and a semester at UNCs Institute for the Arts and Humanities allowed me to begin writing. Generous funding from the John S. Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities gave me a year to complete the writing and revisions. In St. Petersburg, I have long depended on the professionalism of staff at the Saltykov-Shchedrin Library, complemented by the help I received from Nadia Zilper at the Davis Library in Chapel Hill. I thank Fred Stipe in particular for his help with the illustrations, and Jacqueline Solis for her detective work ferreting out sources. At Cornell University Press, I thank Mary Petrusewicz for her careful copyediting, Karen Laun for the skill with which she guided this book through production, and am again grateful to be working with John Ackerman, whose sense of humor remains as sharp as his editing pen.

My deepest appreciation lies with my sister Betsy. Our road together to murder began in West Hollywood on Poinsettia Drive, during those lazy summer evenings with burgers on the grill, margaritas in the blender, and Police Woman on channel 9. We still laugh about watching Dragnet in Oakland, sitting on the floor because my couch had no springs. Our brush with true crime came while cheering for the Knicks in the 1994 NBA finals, coverage interrupted by the police chase of O. J. Simpson in that infamous white Bronco. We have enjoyed so much together, from Caesars Palace to St. Petersburg, that a catalog of our misadventures would read longer than this book. To quote our mutual friend Tania, Betsy is a remarkable person. You are fortunate to have her in your life. I am indeed.

NOTE ON DATES AND NAMES

Unless otherwise noted, all dates are given according to the Julian calendar, which in the nineteenth century was twelve days behind the Gregorian calendar used in the West, and thirteen days behind in the twentieth century. In transliterating Russian titles, quotations, and names, I have used a modified version of the Library of Congress system by conforming the old orthography to modern usage. In addition, when giving the first names of individuals, I have omitted diacritical signs and the additional i, and have also Anglicized versions of well-known names and places.

Some material presented in chapter 4 appeared first in Who Cares Who Killed Ivan Ivanovich?: Detective Fiction in Late Imperial Russia, Russian History 36, no. 3 (2009); and material from chapter 5 appeared in Ubiitsa v gorode: Narrativy urbanizatsii, in Kul tury gorodov Rossiiskoi Imperii , ed. Mark Steiner and Boris Kolonitskii (St. Petersburg: Evropeiskii dom, 2009).

INTRODUCTION

One day perhaps the leading intellects of Russia and of Europe will study the psychology of Russian crime, for the topic is worth it. But this study will come later, at leisure, when all the tragic topsy-turvydom of today is behind us.

The procurator in The Brothers Karamazov , 1866

The man delivering water heard only a dog bark when he knocked at a first-floor apartment in the Iakovlev house in Gusev Lane on June 4, 1867. The blinds were drawn, suggesting that all were still asleep. This surprised the dvornik (janitor), because the people who lived there tended to be early risers. He roused the owner of the building, who brought a locksmith. Ultimately they got in through an open fortuchka , a small window in the back. The scene inside shocked every sensibility: In the bedroom, next to each other, lay the bloodied corpses of Colonel Vasilii Ashmarenkov and Elena Grigoreva, the lady passing as his wife. Their heads were bashed in, and her legs tangled in the sheets as though she had tried to get up. Moans drew them to the adjacent room, where the scarcely breathing body of gymnasium student Sergei Petrov lay under the divan. The boy would not survive. The body of servant Agrafena Babaeva, her skull smashed, lay face down across the doorway between the hall and the living room. The investigation turned up blood-encrusted hand irons and a log with traces of blood and dog hair. One dresser drawer had been emptied, but silver icons still hung on the walls. Government bonds lay stashed in the oven, but no cash. The absence of signs of forced entry pointed toward the attacker as someone familiar with the apartments inhabitants. Only Sergeis tortured dog would pull through.

Law enforcement officials looked no further than the courtyard for suspects. They arrested Iakim Fedorov, the dvornik , Anna Andreeva, a widow who lived on the premises, and Maria Korneeva, a washerwoman who had been at the house the day before the murders. The evidence against these three was flimsy: the investigation had turned up an overcoat belonging to Grigoreva in Andreevas room, Korneevas shoes in the victims apartment, and blood stains on various items in the possession of all the accused. Korneeva claimed to have drunk to excess at the Peking traktir (tavern) on the night in question, accounting for the blood on her sleeve from the spill she took when staggering home. Alibis did not hold up, and the suspects gave contradictory testimony.

Arrested within days of the crime, these wretched three were still languishing in jail eight months later when an additional suspect popped up. Grigorevas nephew had come to clean out the apartment, and found a bloody shirt stuffed in a steam pipe. A tag identified it as belonging to Daria Sokolova, a soldiers wife from Orlov Province, who had worked for Ashmarenkov some years back. The police sent an official to investigate, and he found items of Ashmarenkovs jewelry locked in a box. Details of the arrest then become murky. Sokolova had reputedly told the investigator that she had spent the night with her former employer because she had missed the train back to Orlov. She subsequently confessed to having awakened with an inexplicable desire to kill them all. Once in Petersburg, she recanted that version, insisting that the investigator had promised her exoneration if she would return and tell this story to a general. What she got was newly appointed chief of detectives I. D. Putilin, to whom she admitted being in the apartment that night. In the revised account, she hid under the divan, listening to the voices of killers she could not identify. No evidence connected Sokolova to the others accused, but they stood trial together, formally charged with premeditated murder for purposes of theft.