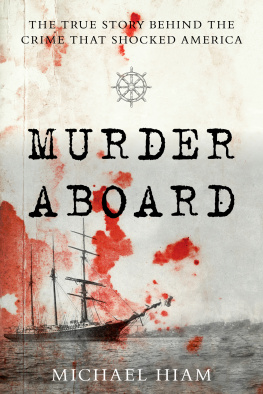

INTRODUCTION

W ith plenty of Hindenburg tickets still available, Margaret G. Mather, an American in Europe wanting to return home, thought of buying one for New York. Although an experienced air traveler, she recalled her strange reluctance to make the purchase, but then she considered the alternative, which was to cross the Atlantic in increasingly luxurious steamers, whose lavish comfort and entertainment meant little to a sea-sick wretch like herself. She would fly. At a Frankfurt hotel she had her ticket and passport inspected, and then the luggage examination began, she said. It was courteous but very thorough; every inch of my bags was searched, every box opened. I had to pay for fifteen kilos overweight, and tried to argue that point, as I weigh twenty kilos less than the average man, but I was told it is the rule.

Mather and thirty-five other passengers, half the Hindenburgs usual complement, took a bus from the hotel to the airport, and when she saw the great silver airship tethered to the ground, a wave of joy swept over her and, she remembered, Gone were all my doubts and reluctance; I felt all the elation and pleasure that had failed me until now. Retractable steps led her aboard, where on the lower deck she located her cabin, finding it very tiny but complete, with washstand and cupboards and a sloping window. The room also had a narrow but comfortable bed furnished with soft, light blankets and sheets of fine linen, the same material that lined the pearl-gray walls. Having explored her lodgings, she went upstairs to join the other passengers leaning over the lounge windows to watch the ascent. The ground crew had just released the ropes and, this being Germany in 1937, a brass band thumped out martial music while little boy Nazis scurried after the rising airship. It was an indescribable feeling of lightness and buoyancy, she recalled, a lift and pull upward, quite unlike an airplane.

The Hindenburg might have been the sturdiest airship ever built, but like all airships it bruised easily when earthbound, and so departures came at either sunrise or sunset, when winds were lightest. For this reason lift-off had taken place at sundown, May 3, and through the growing dusk the passengers strained to catch a glimpse of the Rhine somewhere below. Flashing beacons guided the dirigible from hill to hill as it passed over hamlets and villages gleaming jewel-like in the darkness, Mather said, before coming to Cologne and a spreading mass of lights that silhouetted the citys famous cathedral. At 10 p.m. she and her fellow travelers sat down for a late supper of cold meats and salads.

Unattached passengers ate together at a long table and Mather, as the lone single woman aboard, found herself placed at Captain Max Prusss right elbow. She thought the captain both professional and genial, and the following day, May 4, he confided in her that because of the weather this was one of the worst trips he had ever made. Conditions outside may have been appalling, yet inside the airship Mather observed that one felt no motion, though the wind beat like waves against the sides of the ship. It was almost uncanny. Enjoying the chance to rest, she spent most of that day looking through my sloping window at the angry waves, whitening the sea so far below.

Living with others in close quarters allowed Mather to make acquaintances, acquaintances that at the end of any other airship voyage would likely have resulted in years of mutual correspondence, and perhaps hopes for a happy reunion. Among those she got to know included a red-faced man who drank and a gentle elderly couple from Hamburg who loved the Hindenburg and held tickets for a return flight. There was also a family aboard with a well-behaved girl and two boys that Mather liked to watch, the children obviously enjoying the trip so much. Among the other travelers heading to the United States were young American men happy to be going home, where, one of them told her, you could drink plain water and theres no bother about passports. Mather also befriended a Long Island couple returning from a brief business trip but whom, to protect their privacy in death, she subsequently named only as Mr. and Mrs..

On the afternoon of May 5, the second full day of flight, Newfoundland came abeam and the winds lessened. The airship flew low, as low as six or seven hundred feet, over gray waters speckled with white icebergs. A double rainbow completely encircled the ship. That night, Mather slept like a child. At dawn, with no more land in sight, bad weather returned, and in Germany, where every day of every flight of the Hindenburg made news, the Berlin papers reported the airship being twelve hours behind schedule. Whether Mather knew of this she did not say, but its unlikely she would have complained about additional time aloft. Indeed, when Boston suddenly appeared below on the morning of May 6, she turned to a fellow traveler and said of herself, It is ridiculous to feel so happy.

The vessels in the harbor saluted the flying leviathan with horns and whistles, and in the suburbs cars pulled to the curb and their occupants leapt out to look heavenward. Resembling bees buzzing a bear, diminutive airplanes flew close to the giant dirigible as it headed toward Providence, Rhode Island. Then, over Long Island Sound, an excited Yalie searched the landscape to the north for a glimpse of his alma mater, and to the south Mr. and Mrs. showed Mather the bay where they lived and explained that their son would drive to Lakehurst, New Jersey, to meet them at the air station. Next, the Hindenburg reached Manhattan, and like a tourist taking in the sights, passed over Fifth Avenue and Central Park before heading west. Lakehurst was only fifty miles distant, and the airship arrived within the hour. Mather, however, noted a line of black clouds and bright lightning in the near distance, and saw that no attempt was being made to land.

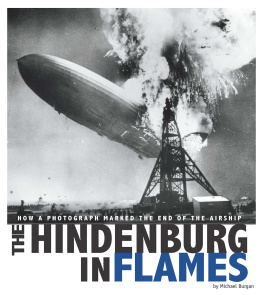

As if patiently awaiting its appointment with fate, the Hindenburg left Lakehurst and marked time by flying over the beaches and forests of New Jersey or making short sorties out to sea. Mather was also in no rush, and remembered that I was feeling foolish with happiness and didnt really care how long this cruising lasted. The stewards served an early tea, followed at 6:30 p.m. by sandwiches because, the passengers learned, the atmospherics remained unsettled and the ship might have to linger in the air for an hour or so longer. Apparently a decision to land had then been made by Pruss in the control car, and all at once they were over Lakehurst again. In rapid succession the airship circled the mooring mast, speed and altitude were reduced, ropes were thrown down, and as she leaned out an open window in the dining salon, Mather said she heard the dull muffled sound of an explosion.

An imprint of University Press of New England

An imprint of University Press of New England  www.upne.com

www.upne.com All rights reserved

All rights reserved