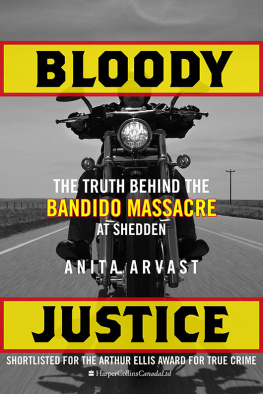

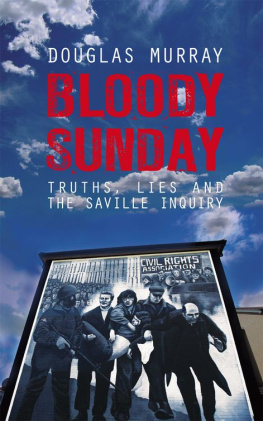

This book would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of many. Primarily, I wish to thank all those who lost someone on Bloody Sunday and all who survived and spoke with me at great length about these deeply personal experiences. Collectively, they helped me understand the true extent of the events of 30 January 1972 and the reasons why the Bloody Sunday Justice Campaign was so important. I only hope this book does your story justice.

Also to their fellow campaigners, supporters, lawyers and politicians who gave so freely of their time to speak with me about their involvement. This, too, is their story.

I am indebted to my colleagues in the Bloody Sunday Trust who commissioned me to undertake this project. Thanks to them for their advice, faith and encouragement and for their contribution to this book. Also to Adrian Kerr and all at the Museum of Free Derry for their support and permitting me access to their invaluable archive of material relating to Bloody Sunday and the campaign.

I am deeply grateful to Conal McFeely, Joan and all at Creggan Enterprises and Rth Mr for providing a quiet space in which to write and with the financial assistance to do so thank you.

To Sean McLaughlin, who helped me delve into the vast Derry Journal archives and whose advice helped me shape both the style and the substance of the book; and to Eamonn McCann, Chair of the Bloody Sunday Trust, for consistent advice, passion, and his skilled proofreading of its final chapters.

To all my colleagues and friends at the Derry Journal who have supported me throughout this project and to my editors and management who gladly granted me leave to work on it and free reign of the Derry Journal archives. I appreciate it so much. Thanks also to An Cultrlann for hosting the launch in Derry, and to Gareth Peirce for her insightful foreword.

For sound advice, my thanks to Paul Hippsley and all at Guildhall Press; the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs; all at Derry Scriptwriters Group and the University of Ulster CAIN website. I am also grateful to Deputy First Minister, Martin McGuinness and Dominic Doherty of the Derry Sinn Fin office and MP Mark Durkan and the Derry SDLP office.

To Christopher and our darling daughter, Saffron, who showed such over-whelming patience and love as the words consumed me. To my mum, Susie and my four brothers, Paul, Alan, Peter and David thank you for everything. To the Duddys, especially my auntie Kay and uncle Gerry who campaigned on behalf of the whole family and never gave up hope that the truth would be set free.

To Aisling Starrs, for her superb listening skills since this journey began, Mama Cass and all my friends for being there throughout. Thanks to all the photographers who permitted me to use their work in the book Stanley Matchett, Hugh Gallagher, Robert White, Stephen Latimer of the Derry Journal for the author photo, Charlie McMenamin, the Derry Journal archives, Colman Doyle and the National Library of Ireland.

To Sen, Dan, Caroline and all at Liberties Press, Dublin thank you for believing in an idea and seeing it through with foresight and passion. Lastly, to my daddy, Pat Soup Campbell, and my granddad Johnny Campbell, from whom it seems I inherited a love of language and enough eloquence to express it.

In the same year that this record of an extraordinary campaign goes to press, the international community has mobilised to support protestors gunned down by ugly regimes in Libya, Egypt, Tunisia and Syria. In 1972 there was no such aid for the people of Derry; all they had was themselves. The very act of protest had been transformed into a crime. The engines of the British state pumped out an immediate false narrative, endorsed by the Lord Chief Justice of the day. There was no one, absolutely no one, to turn to. And yet not one sane individual of power or influence chose to comprehend the most basic proposition; that criminal state action would fuel reaction. The murders and the narrative that supported the murders, would fuel an armed conflict for decades.

The families of those who died achieved the impossible, compelling the state to pick up the mirror, to recognise itself and finally admit its guilt. The crimes that were committed against those who died were never meant to be exposed to any just scrutiny; there was only ever meant to be one narrative and in the absence of a root and branch revolution it would be thought impossible to shift a false state narrative. That is why what was accomplished by the Bloody Sunday families is so extraordinary and important for others; as the ship of the British state sails on, and continues to construct and perpetuate false narratives against other communities worldwide whom it deems suspect, they gain courage and inspiration from what finally happened in Derry, against all the odds.

At the end of the day the Saville Report itself will not be recognised as the most enduring achievement; that accolade must go to those who took thirty years to bring it about, and another twelve years to see it through. The inquiry itself established less than was comprehended within minutes by the targeted community in Derry. There was to be no moving forward for civil rights through peaceful protest. Bloody Sunday put paid to that and was intended to put paid to it. It is impossible not to see the trajectory. The same parachute regiment had shot down eleven innocent citizens in Ballymurphy the year before; senior police as well as army officers had protested in advance at the madness of deploying that regiment to police a civil rights march in Derry. And at the end of the day, the inquiry, acknowledging the innocence and integrity of the murdered protestors balked at tracing responsibility to the very top.

Although external events shook the fault lines of state complicity in Bloody Sunday from time to time, and although allies whose help had been sought over many years were finally persuaded which was the right side of history to be on, none of those external and accidental events would have ever progressed the possibility of an inquiry, had there not been at all times, for decades, the sustained, demanding moral integrity and stamina of the families. They were the soul, the heart, the iron and the steel. They are all our inspiration; to them the world owes its gratitude and respect.

Gareth Peirce

20 December 2011

Eminent human rights lawyer Gareth Peirce has worked on many high-profilecases, including the Guildford Four, the Birmingham Six, the family of JeanCharles de Menezes and many Guantanamo Bay detainees.

Jackie Duddy, the first person killed on Bloody Sunday, was my uncle. He was just seventeen when he was shot in the back as he ran across the car park of the Rossville Flats. A photograph of Father Edward Daly, later Bishop Daly, waving a white handkerchief as he helped carry Jackies body away from the shooting has become the most enduring image of that day.

I wasnt yet born at the time. But like everyone else in Derry down the years since, I grew up in the shadow of Bloody Sunday. As children we were shielded from the shock of the event. It was considered unwise, or unnecessary, to tell us the truth. We knew only of our fallen uncle, who had died long before wed come into the world. We were told that, back then, he had marched for peace and didnt come home, that soldiers had shot him. We could see from the photographs that he had our familiar cheeky smile. We knew from the trophies that were kept on display in the house and the pictures of him posing in his gloves that he had been a promising boxer with the world at his feet. My wee sparring partner, my mother often calls him to this day.