First published in the UK in 2015 by Intellect, The Mill, Parnall Road, Fishponds, Bristol, BS16 3JG, UK

First published in the USA in 2015 by Intellect, The University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

Copyright 2015 Intellect Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library.

Cover designer: Holly Rose

Copy-editor: MPS Technologies

Production Manager: Tim Elameer

Typesetting: John Teehan

ISBN 978-1-78320-182-2

ePDF ISBN 978-1-78320-265-2

ePub ISBN 978-1-78320-266-9

Printed and bound by Print on Demand, UK

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the following good people for their help and support in the writing of this book: Melanie Marshall, Thomas Newman and Tim Elameer at Intellect, for their patience and their faith in the project; Eamonn McCann, for his excellent foreword; John Kelly and Adrian Kerr at the Museum of Free Derry, for their help, advice and support especially for allowing us access to valuable archive material; Margo Harkin at Besom Productions, for her valuable advice and helpful correspondence; Marie Paton, Director of the Research Office at the University of Ulster (UU), for supporting the project with a generous publishing subvention; the staff at the UU Library Coleraine and the Newspaper Library at Central Library Belfast, for their help with our archive research; Jeremy Shields at BBC NI, for his archive leads; our colleagues in the School of Media, Film and Journalism at UU Coleraine especially, Martin McLoone, Robert Porter and Anne Crilly for their intellectual and research support; Mervyn McKay, for his expert technical assistance; and Sally Quinn for her patient and always good-humoured admin support. We also appreciated the support and comradeship of Cahal McLaughlin at Queens University Belfast and Paddy Hoey at Edge Hill University. Thanks above all to our parents and siblings for not rolling their eyes at the news we were writing another book, at least not to our faces; and, of course, to our nearest and dearest Sue, Kitty, Nye and Ewie for their love, faith and forbearance.

Warm thanks to one and all.

Foreword

That will have to be changed! the senior Government official seethed, face thrust forward, 18 inches from mine.

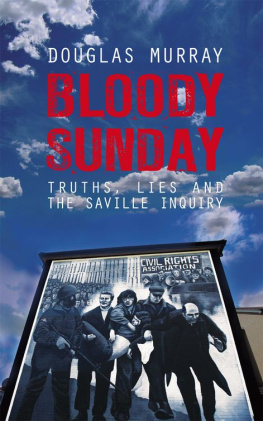

W e were in the corridor of Derry Guildhall at around half past four on the afternoon of 10 June 2010. The Saville Report into Bloody Sunday had been released an hour previously. The families of the victims were making their way out of the building onto a platform to be greeted by expectant thousands of their Derry neighbours. Tony Doherty, whose father, Paddy, had been shot in the back as he crawled for shelter in the lee of the Rossville Flats, was to read a statement agreed by the families.

I had just read out the text to the families to make sure all were content. This was what the Northern Ireland Office chief wanted changed.

The victims of Bloody Sunday have been vindicated, the statement began. The Parachute Regiment has been disgraced. The truth has been brought home at last It can now be proclaimed to the world that the dead and the wounded of Bloody Sunday were innocent one and all, gunned down in their own streets by soldiers who had been given to believe they could kill with perfect impunity.

The statement concluded that, the repression that came upon us was the same as is suffered by ordinary people everywhere who dare stand up against injustice Sharpville, Grozny, Tiananmen Square, Dafur, Fallujah, Gaza. Let our truth stand as their truth too.

The tone was not to the liking of the official. Everybody agreed that this was to be a day of reconciliation, she expostulated, but too late. The families were already trooping out. Tony declaimed the statement as drafted, to rolling waves of approval.

Caught up in the euphoria of the moment, it was hours before her words sank in and I wondered: Who was the everybody who had agreed in advance that a report on the soldiers shooting of 28 unarmed people in broad daylight would make a suitable case for reconciliation? And who was it envisaged would be reconciled with whom? In the North, the word refers almost invariably to mending of relations between the two communities a resolution which every British government since the beginning of the Troubles has pleaded and pledged to work for, all the while lamenting the long history of hatred blighting the incorrigible and largely ungrateful Irish.

But Northern Protestants had played no part in the Derry killings. Bloody Sunday had been a very British atrocity. It thus contradicted the preferred British account of their own role, not just on the day but in relation to Ireland generally. An imperative to promote this depiction of the relationship, more than any other factor, dictated the way the British media had covered Bloody Sunday in 1972 and the context in which the Saville Report was now being presented. Greg McLaughlin and Stephen Baker in this wide-ranging, meticulous analysis peel away the layers of prejudice and presumption to lay bare the politics at the core of British reportage.

The negative portrayal of the anti-internment marchers on Bloody Sunday and the suggestion of significant IRA activity on the day contrasted with an air-brushed and inaccurate account of the paratroopers actions. It had the effect of confirming for British readers and viewers that the soldiers had entered the Bogside with decent intentions and that the ensuing slaughter had essentially been the fault of irresponsible demonstrators and murderous republican paramilitaries. The British were let off the hook.

A number of honourable journalists did their best to hold the line against the lies, but the general pattern was plainly calculated. By 2010, this version had become unsustainable. The relentless campaigning of the Bloody Sunday families and their supporters and the associated intervention of a number of journalists and writers had gone some way to rescuing the honour of the media and had left no room for reasonable doubt that the Bloody Sunday deaths had been unjustified and unlawful.

Reflecting this changed perspective, the line of most of the British media now was that the admittedly inexcusable actions of the paratroopers, the death-storm they had inflicted on the Bogside, could and should be put in the past. Saville had exonerated the victims and prime minister Cameron had accepted his verdict. The families had been given almost everything they had asked for. Time to move on. The report should be seen as an occasion for reconciliation, thus to enhance the peace process.

I dont need anybody to reconcile me with the British people, commented Liam Wray, whose brother Jimmy had been gunned down in Glenfada Park. I have never been estranged from them. But reconciliation with the British establishment, after all it had done in the North over the last 40 years not just on one day in Derry thats a very different proposition.

The fact that it was the British ruling class, rather than the masses, much less the Northern Protestant community, who were expected now to be hugged in forgiveness, was made explicit in the suggestion of mainstream Westminster opinion in the days following publication of the report, faithfully reflected in the media, that conditions were now propitious for the monarch to visit the Republic and seal the deal. In the days after Saville, there was a remarkable plethora of media proposals in the