Aids Activist

2003 by Ann Silversides

First published in Canada in 2003 by

Between the Lines

401 Richmond Street West, Studio 277

Toronto, Ontario M5V 3A8

1-800-718-7201

www.btlbooks.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be photocopied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Between the Lines, or (for photocopying in Canada only) Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario, M5E 1E5.

Every reasonable effort has been made to identify copyright holders. Between the Lines would be pleased to have any errors or omissions brought to its attention.

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada.

ISBN 978-1-771130-43-1 (epub)

ISBN 978-1-896357-73-3 (print)

ISBN 978-1-771130-44-8 (PDF)

Cover design by David Vereschagin, Quadrat Communications

Front cover photograph by David Vereschagin

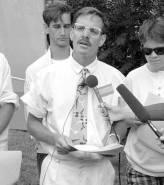

Photo of Michael Lynch, opposite title page, courtesy of Philip Hannan

The silhouette image on p.xiii is taken from the Numbers poster; see p.135.

Text design by Jennifer Tiberio

Between the Lines gratefully acknowledges assistance for its publishing activities from the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishers Tax Credit program and through the Ontario Book Initiative, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program.

FOREWORD

ONE OVERCAST New York afternoon in June 1994, a rented yacht idled under the Brooklyn Bridge. A group of friends, myself included, were gathered on board to carry out a final act of memorial for Michael Lynch. Before Michael died in 1991, he had asked that his ashes be scattered from the bridge that had so inspired one of his favourite poets, Hart Crane. A trademark Michael wish, and so here we were at last, three years later, drawn together in New York for the twenty-fifth anniversary celebrations of the Stonewall riots, the symbolic birth event of the gay liberation movement.

The request had seemed simple enough to carry out (not without some effort and inconvenience, of course) until Michaels son Stefan discovered that the design of the pedestrian walkways made ash-scattering from the bridge virtually impossible. Now what would we do? Finally, someone made the obvious suggestion. Why not use a boat?

Our vessel had taken us to a spot on the East River in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridges massive suspension spans. Once moored, we read selections from Michaels favourite poets, lifted glasses of champagne in a toast, and tossed overboard brightly coloured gerberas (one of Michaels favourite flowers). Finally, as the boat picked up speed to return to shore, we took turns dropping Michaels ashes from a container into the river. Then, unexpectedly, lifted by a gust of wind, plumes of fine ash flew back into our faces and clothes, dropping tiny spots on the remaining champagne in our glasses. We contemplated the silly symbolism of this moment, and our tears turned to laughter as we made our way back to dock.

Even during this final act of memorial, it seemed, Michael had once again managed to leave his mark on his friends. I was certainly one of the people who had felt enriched by Michaels friendship over the years. But whose lives beyond his circle of friends did he touch?

An American by birth, Michael moved to Canada in 1971 to take a job teaching English literature at the University of Toronto. In that city he became one of a group of individuals associated with The Body Politic, a gay liberation magazine whose advocacy journalism became an inspiration to activist circles around the world. The decade of the 1970s, punctuated at its end by sensational courtroom trials, chilling police raids, and angry demonstrations, proved to be a valuable training ground for Michael and a cadre of activists schooled in the rough skills of movement journalism and committed to the politics of collective action. The lessons he learned from gay organizing in Toronto during those early years, fuelled by his personal grief over friends suddenly snatched away by AIDS , gave him the vision to inspire others to resist, to organize, and to mourn during the toughest years of the AIDS crisis in Toronto.

Michael did not fit any of the mass media-inspired caricatures of the one-dimensional activist. His interests were remarkably diverse. In addition to his pioneering pieces of advocacy journalism in The Body Politic and his AIDS organizing, Michael taught the first gay studies course at the University of Toronto, founded Gay Fathers of Toronto, edited the first lesbian and gay studies newsletter in North America, launched the first community-based queer studies organization in Canada, and published a book of poetry. He fulfilled a personal fantasy by posing for nude spreads in two gay erotic magazines. He loved to haunt the disco dance floors in New York and Toronto, and threw fabulous parties. Throughout all of this, before he died of AIDS at the age of forty-six, he managed to raise a remarkable son.

In 1982 and 1983, with the arrival of the mysterious illness, the sudden deaths, and the confusion and fear they brought, Michael Lynchs plea for an organized and calm resistance strategy in the face of the pending crisis helped to shape an entire communitys response to AIDS and keep it true to the principles of sexual liberation and democratic organizing. Throughout the worst of the AIDS years in the 1980s, his was one of the primary voices of reason and passion within Torontos gay community. Michael managed always to bring a calming influence to organizational politics. He understood the different roles that organizations and institutions could strategically play in responding to a health crisis like AIDS . He recognized the need for healing rituals to give public expression to private grief, to commemorate, in his words, these waves of dying friends. In Michael Lynchs world, there was a place for both mourning and militancy.

Looking back now at those formative years, we can say that the gay community, inspired by the strength and vision of early AIDS activists like Michael Lynchand there were, of course, countless others who shared in this workmade the right choices in its responses to the epidemic. Its legacy is a network of diverse AIDS service organizations serving the needs of diverse communities. Whole new generations of queer youth have never known anything but the persistent warning theme of AIDS and safer sex running in the background of their lives. Medical advances in drug therapies have prolonged many lives, and AIDS deaths are no longer frequent or inevitable.

Yet in some cases the welcome sense of confidence and entitlement that young people feel today is also creating a less desirable legacy: complacency about condom use and boredom with safer needle and safer sex advice. There is no longer an overwhelming sense of urgency or crisis driving the HIV / AIDS agenda. Rates of infection among young gay men are reportedly on the increase, and the slow attrition of funding for HIV prevention programs barely registers on the medias radar screen.