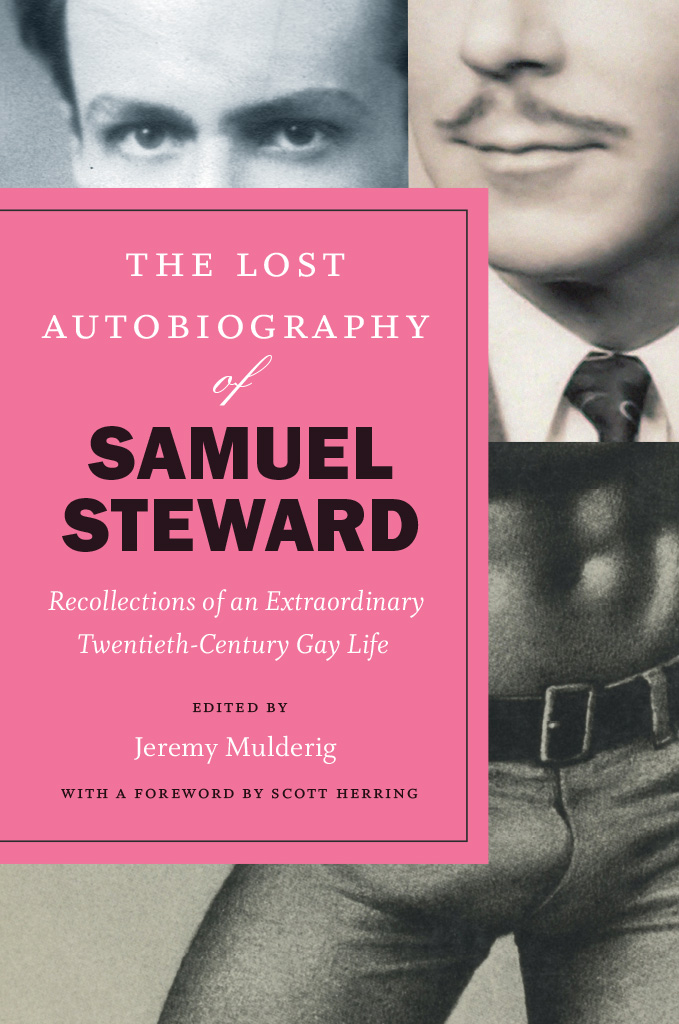

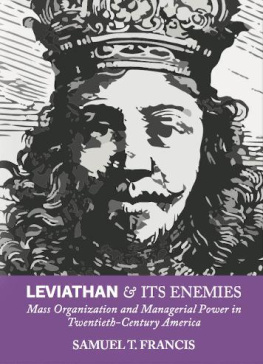

The Lost Autobiography of Samuel Steward

The Lost Autobiography of Samuel Steward

Recollections of an Extraordinary Twentieth-Century Gay Life

edited by Jeremy Mulderig

with a foreword by Scott Herring

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2018 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-52034-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-54141-9 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-54155-6 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226541556.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Steward, Samuel M., author. | Mulderig, Jeremy, editor. | Herring, Scott, 1976 writer of foreword.

Title: The lost autobiography of Samuel Steward : recollections of an extraordinary twentieth-century gay life / edited by Jeremy Mulderig ; with a foreword by Scott Herring.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017036831 | ISBN 9780226520346 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226541419 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226541556 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Steward, Samuel M. | Authors, AmericanUnited States20th centuryBiography. | Gay menUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC PS3537.T479 Z46 2018 | DDC 813/.54 [ B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017036831

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To the memory of Jon and Nancy Wallace

Words are easy, like the wind; Faithful friends are hard to find.

Courtesy of the Estate of Samuel M. Steward

I was in no sense a case of multiple personalitieslike the three faces of Eve or the extraordinary young man with some ten or twelve differing selves. Butalthough the simile is not a good one, nor very imaginativeI did in a sense have an old artichoke heart, and the various pen names I used in the things I wrote, my Sparrow name as a tattoo artist and later the Andros name as a writer, were like the separate leaves that are capable of being stripped away. But what was at the center?

Samuel Steward

Contents

The choicest task that awaits an authorbesides finishing a bookis titling it. Sometimes the writer makes this decision from the get-go. At other times, a working title such as James Joyces Work in Progress becomes Finnegans Wake. Or James Weldon Johnson commits to The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man after he entertains The Chameleon. Or Djuna Barness Nightwood starts off as Bow Down. What Jeremy Mulderig presents here is an expanded version of a remarkable but forgotten gay autobiography of the twentieth century, which, thanks to his meticulous editing, now earns its new title, The Lost Autobiography of Samuel Steward.

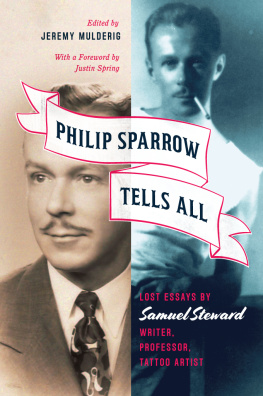

Mulderigs introduction notes that Samuel M. Steward originally considered various titles after he finished his manuscript in the winter of 1978, including A Triple Lifea reference to three of the many personal and professional identities that he adopted during his eighty-four years of living: his role as a university professor for twenty years, his alter ego as a tattoo artist (Phil Sparrow), and his pseudonym as a writer of pornography (Phil Andros). Other titles that Steward mulled over included Things Past, Three Lives in One, and, amusingly, Three-Way. The allusions to his modernist literary heroes Gertrude Stein and Marcel Proust are clear enough and evidence Stewards lofty aspirations. A potential title such as Three-Way also reveals a campy worldview that he wielded throughout his writerly life and that Mulderig carefully excavated earlier with his wonderful edited collection of Stewards mid-twentieth-century essays, Philip Sparrow Tells All: Lost Essays by Samuel Steward, Writer, Professor, Tattoo Artist (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

What if we approached this working titleThree-Wayas a thematic guide for understanding Stewards multiple personae? What does it mean to have a threesome with yourself? Or to imagine your triple life as a Three-Way? Stewards sexual contacts, which his memoir discusses at length, numbered well into the quadruple digits. But one of Stewards most important relations was with and to himself. I mean this self-relation both literally and figuratively. As we learn early in The Lost Autobiography of Samuel Steward, after departing from the small town of Woodsfield, Ohio, Steward prized his young-adult life in the greener urban pastures of Columbus. I went to Columbus, he writes, with the major purpose of bringing pleasure to others, mainly straight young men, and not to be concerned about pleasuring myselffor in bringing it to those I admired, I did please myself. Later in his autobiography he references shaferinghis idiosyncratic term for masturbatingwith Lord Alfred Douglas as well as with his Accu-jac device, a masturbation machine he owned during his later life in the Bay Area. Along with [Jean] Genetwho first suggested itlet us form a cult of the solitary pleasure, he writes in his first chapter. Pleasing this solitary self, he engaged with the wider world of male same-sex desire.

Stewards focus on self-pleasure also applies to the various selves that his autobiography details. The link between autoeroticism and writing is an old saw but one still germane to this writing at hand. It is hard not to read Steward, drafting prose at age sixty-nine, taking supreme delight in reliving the exploits of Andros and Sparrow. Writingitself a cult of the solitary pleasurelinked him to these two past lives as the sections of his memoir add up to a figurative three-way with his younger selves. Published in 1981, Chapters from an Autobiography enabled him to revisit these experiences in a compressed version. The Lost Autobiography of Samuel Steward shows in even greater depth how he imaginatively cruised the twentieth century that he lived and loved so intensively. Indeed, Mulderigs edition confirms Stewards to have been a life full of hindrances but also sincere pleasures of which he took full advantage. Between the pages of these lengthened chapters, we have a wide-eyed Steward meeting Stein and Alice B. Toklas in Bilignin, France; a Steward who became one of the most admired tattoo artists in the Midwest; an aging Steward who moved to Berkeley, California, and struggled with its youth-obsessed gay communities. He notes that his time spent in Berkeley was a tumultuous period, and that is quite the understatement. With The Lost Autobiography of Samuel Stewards references to major historical events such as World War II and what one anthropologist, Kath Weston, terms the Great Gay Migration to cities that started in the later 1960s, we have an account of a gay male who lived through every decade of the twentieth century. The act of recording these past events and prior selves clearly gratified him: referring to his pseudonym, Steward observes, Phil Andros, springing full-grown from my temple, like Athena from the brow of Zeus, was a pleasant surprise, helping me to pass the time. In him and through him for several years, I relived not only the adventures of my own youth but those of several others I had known.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).