The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Leon and Ewa and Bolek and Mila

Contents

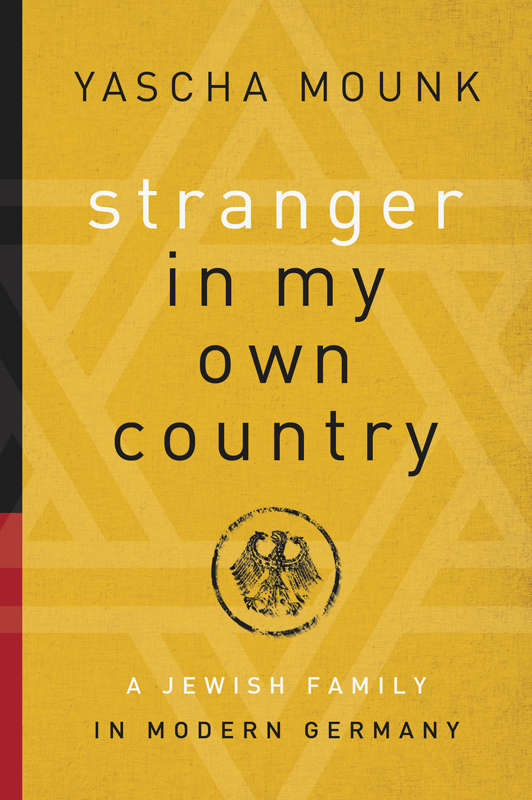

Prelude: An Unlikely Refuge

I never thought to question why my family might be so small, or so scattered. In Munich, there was my motherAlaand me. Relatively close by, in Frankfurt, there was my grandfather Leon. Far away, in southern Sweden, there was my grandmother Ewa, my uncle Roman, and my cousin Rebecka. There was also my great-uncle, a man by the name of Herrmann, but he lived even farther away, in San Francisco. As I was told whenever his name came up, he was, in any case, not much of a family man. I saw him just twice in my life.

That was it. Six of us. Seven, if you counted generously.

It seemed natural to me, of course, just as most children, even those who grow up in circumstances they later recognize to be unusual or downright bizarre, think that their reality is normal, natural, even inevitable. I simply assumed that families everywhere come in small sizes, that a reunion of three full generations never amounts to more than seven people.

Only much later did I understand that none of this was natural; that, on the contrary, it was the result of historical forces I might be tempted to call abstract, had they not had such a tangible effect on the world I grew up in.

No, it was not natural that my family was so small, for Leon and Ewa should have had parents who might still have been alive when I was born. Leon should have had seven siblings, not just Herrmann. Ewa should have had an older sister, as well as many cousins, aunts, and uncles. Even Roman and Ala should, I eventually learned, have had a big brother.

Nor was our dispersal, a good two decades after the death of so much of my family, natural. It was the result of a second manmade tragedya much smaller tragedy, to be sure, but one that, in its own way, dispensed with my grandparents lifelong hopes and aspirations in just as comprehensive a manner.

Ever since they were teenagers, Leon and Ewa had devoted their lives to an ideology that promised to rid the world of ethnic persecution: communism. But, in the event, the Communist government of Poland ended up throwing themits most loyal aidesout of their homeland for no better reason than that they were Jews. It was in the wake of this second tragedy that my family dispersed to the United States, to Israel, to Swedenand to Germany, where I was to grow up.

* * *

Leon first considered moving Ewa, Ala, and Roman out of Poland in 1956.

With an unprecedented speech to the Soviet Communist Party, Nikita Khrushchev had just denounced the terrible abuses of Stalinism. In Poland, the effects of this speech were immediate. The hard-line policies of the last years softened a little, making it much easier for Jews to obtain exit visas. At the same time, a significant part of the population used their newfound political freedom to give voice to the same old anti-Semitism.

A prominent political faction, the so-called Natolin Group, publicly stoked the anti-Semitic mood of the day with thinly veiled attacks on Zionist traitors who supposedly remained at large in Poland. Even Wadysaw Gomuka, the newly appointed secretary general of Polands Communist Party, began to flirt with anti-Semitic sentiments, encouraging anybody who wanted to stick to his Jewish identityanybody who expressed solidarity with Israel, or merely wore a yarmulke in publicto leave the country.

Not surprisingly, many Polish Jews proved unwilling to sacrifice their identity in so radical a way. Between 1956 and 1958, half of the seventy thousand Jews who still remained in Poland fled the country. But Leon was not one of them.

* * *

Leon had been born on Christmas Day, 1913, in Kolomea, a little shtetl in the easternmost stretches of the fading Austro-Hungarian Empire. The faces of his childhood are the faces you see in those old photographs that chronicle the lost world of traditional Eastern European Jews: bearded men in dark jackets; women in modest, flowing robes; joyful children, momentarily forced to sit stock-still, visibly impatient to escape the photographers lens and get back to playing.

Leon grew up in just such a traditional family, together with his parents and grandparents and seven brothers and sisters. But he found his shtetls way of life outmoded and considered its poverty a terrible injustice. And so he was particularly receptive when older children started to talk to him about the ideals of communismabout a world in which all the prejudice of tradition would be done away with, a better world in which everybody would be equal and nobody would have to go hungry. When he was no older than sixteen, he ran away from Kolomea.

The Communist movement became his home and his educator. Leon moved to nearby Lvov, where he found work as a printers apprenticethe most intellectual of manual jobs, for it consisted of reading texts and then setting them in type, letter by letter. But his main interest was his after-hours work as an organizer for the Polish Communist Party, an illegal activity for which he was even prepared to go to jail. Far from discouraging him, his repeated stints behind bars only made him a more fervent activist.

And so, when the Nazis broke their pact with the Soviet Union and moved on Lvov in late June of 1941, it was only natural that Leon should turn east for help. In double dangerbecause he was a Jew and a Communisthe managed to flee Lvov on the last train for Russia before the Germans arrived. For the rest of the war, he was put to work in a makeshift ammunitions factory in Siberia, where he performed dangerous tasks for interminable hours, subsisting on scraps.

That harsh treatment made Leon the luckiest member of his family. Both his parents perished in the gas chambers or were shot dead in some Eastern European ditch. Of his eight brothers, only one, my great-uncle Herrmann, survived.

With most of his family dead, Leon, like so many others in the same situation, must at times have thought it impossible to go on. In those desperate moments, it was his faith in communism that provided a bridge between his prewar and his postwar self. He now thought it more imperative than ever to create a new, better kind of society.

As the Iron Curtain descended upon Europe and Poland found itself under Soviet hegemony, Leons political dream finally came true: the new Poland would be Communist. The contacts Leon had made in a lifetime of political activism now stood him in good stead. After a few years in Lodz, where Ala, his first daughter, was born in 1947, he moved to Warsaw, quickly rising through the ranks of the Communist regime to become the technical director of RSW Prasa, postwar Polands largest printing conglomerate.

But even though Leon had been a Communist his whole adult life, and was now a moderately important man, he wasnt blind to the injustices of the Eastern bloc. One sunny afternoon in March of 1953, when Ala was five, she came home from school crying.

What happened, Alushka?

It is father Sta Ala had trouble speaking between sobs. It is Father Stalin. Father Stalin has died.

Leons face hardened. You, my daughter, he demanded, will not shed a single tear for that swine.