Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Sheree Scarborough

All rights reserved

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62585.020.1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Scarborough, Sheree.

African American railroad workers of Roanoke : oral histories of the Norfolk and Western / Sheree Scarborough.

pages cm. -- (American heritage)

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-504-2 (paperback)

1. African American railroad employees--Virginia--Roanoke--Interviews. 2. Norfolk and Western Railway Company--Employees--Interviews. 3. African Americans--Virginia--Roanoke--Social conditions--20th century. 4. African Americans--Virginia--Roanoke--Social conditions--21st century. I. Title.

HD8039.R12U696 2014

331.63960730755791--dc23

2014015051

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Foreword

PIECES OF A LARGER MOSAIC

During the early summer of 1948, my mother took me on a train trip to New York City. I was five years old. We boarded a Norfolk & Western passenger train at the depot in Buena Vista, Virginia, on a pleasant summer evening. There are not many things that I remember about that evening because far too many years have passed. Yet the excitement of watching that large train speed into the depot has always been one of my more pleasant memories. I also vaguely remember the conductor in his dark uniform and the porter in his starched white jacket. The conductor was white, and the porter was black. Whether or not, at five years of age, I remembered that one was black and the other white is unimportant. During the Jim Crow era, jobs on southern railroads were clearly segregated by race. In part, African American Railroad Workers of Roanoke: Oral Histories of the Norfolk and Western tells the story of black railroad employees in Roanoke, Virginia, as they remember it.

The train that I boarded with my mother would have originated in Roanoke, about forty-five miles south of Buena Vista. Roanoke is a postCivil War boomtown that attracted many new residents during the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Its rapid growth was remarkable; by 1900, it ranked as Virginias third-largest city. In 1890, its total population was 16,159, 70 percent of whom were white.

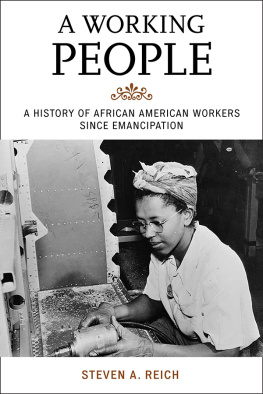

Black labor on southern railroads dates to the antebellum era, when enslaved people toiled to construct tracks. Railroad companies had two options: renting or owning enslaved people. They did both. Constructing tracks was backbreaking and grueling work during the years prior to the Civil War, and it would remain so during the twentieth century. After 1876, some southern railroad companies in the lower South would move from slavery to convict leasing as a means of obtaining an abundant supply of cheap laborers. Such workers were no more than slaves. Many of the convicts were guilty only of breaking the Souths vagrancy laws. These were statutes that entrapped out-of-work black men. Convict leasing provided income for southern states and cheap labor for the railroads and was less humane than slavery. The living and working conditions of these men were deplorable. Fortunately, Norfolk & Western was not built by convicts.

The significance of jobs with Norfolk & Western is that the company paid salaries to blacks, no matter how menial those early jobs were. Pay was relatively low, but the work was steady because of the boom in southern railroad construction that began in 1879. Within the first ten years, southern railroads increased from 16,605 miles to 39,108 miles, thanks in large part to the investment of more than $150 million in capital by northern and foreign entrepreneurs.

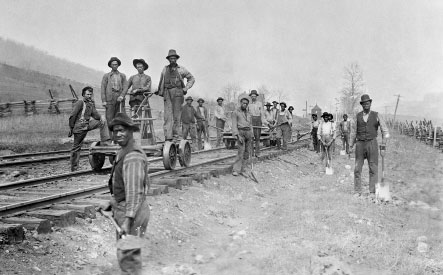

Rail gangs used hand tools such as pickaxes, shovels, tie tongs and mallets to repair and replace track. Norfolk Southern Corporation.

In spite of economic progress, Norfolk & Western was a southern company that was bound by Jim Crow laws and customs. And so was the booming city of Roanoke. Norfolk & Western jobs continued to be very important to workers and their families but were clearly defined by race. Restriction of job opportunities by race was worst, however, in the North and other regions. Historian Eric Arnesen has written that railroads had something of a labor aristocracy that placed engineers and conductors at the top. He notes that skills and ethnicity defined who held those privileged positions. Their wages, authority and autonomy placed them at the top, where their compensation and independence was impressive. Engineers had the greatest responsibility and had to master the technology and direct the trains physical operations. Conductors, who ranked second, supervised the brakemen and porters. They were also responsible for the freight. Locomotive firemen and brakemen performed vital but dangerous tasks and occupied a lower place in this labor aristocracy than did the engineers and conductors. Only the porters were black.

As late as the 1950s and 1960s, some trades among American railway workers continued to be racially and ethnically homogenous. Locomotive engineers and conductors were white. Northern and western white men, who had long been entrenched in these jobs, insisted on a strict color line that effectively prevented competition from blacks or other racial and ethnic groups. To some extent, blacks outside of the South worked in dual roles as brakemen and porters. In the South, however, the situation was a bit different. Southern railroads offered a wider variety of jobs to black workers. By the beginning of the twentieth century, blacks held the majority of firemen and brakemen jobs on many of the southern lines. Both were essential jobs that entailed hard work and risk of bodily harm.

During the twentieth century, railroad brotherhoods or labor unions evolved. Initially, these groups barred black membership and worked to prevent blacks and various ethnic groups from competing for the white jobs that paid better. The southern states in general and southern corporations in particular were hostile to unions. Typically, unions had little influence in the South, although they had many good features. Most importantly, they attempted to protect workers from unsafe conditions and provide insurance benefits. The Roanoke workers, who are the subject of this book, belonged to the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks (BRAC). Their experiences are interesting because some were already working for the railroad before the racial changes that occurred nationally during the 1960s. Some of them briefly remarked on joining the union and their perceptions of membership. Not surprisingly, their job orientation seldom provided information about the union. Several respondents suggested that the need for joining the union and the subject of dues were matters that they later learned about sometime after beginning work for N&W. Some respondents did not mention the union at all, while others were vague about its necessity or functions. The two most eloquent responses about union membership came from John Mease, who spoke about the Norfolk & Western strike of 1978, and Mike Worrell, who serves as president of Division 301 of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen. As an African American engineer whose father was an active union member, he asserts that the unions gave a lot of people weekend pay, weekends off, set work schedules and [provided] good, safe work environmentsand today we try to still follow that. For Worrell, unions facilitate safe working conditions and protect the rights of employees.