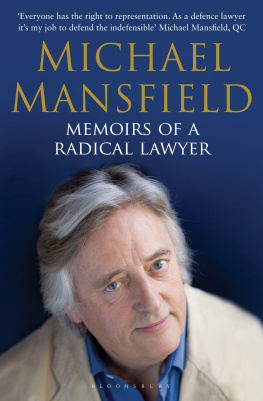

Memoirs of a Radical Lawyer

MICHAEL MANSFIELD

with Yvette Vanson

To Yvette without whom this book would never have been written

and

To all my lay and legal clients without whom there would have been no story to tell

Contents

This is a memoir. Not an autobiography cradle to grave let alone some tedious detailed diary, but a collage of recollections and reminiscences, which are gathered together around issues that I feel are important, and which arise from some of the cases I have undertaken. Personal stories punctuate the themes, but only where there is a natural connection. No confidential information about anyone Ive ever represented is used or divulged; not every trial, not every person gets a mention which does not imply that the omissions are less important. Where a case is described in some detail, I do so to highlight what went right or wrong, or what needs to be changed in our legal system.

Roll up the shutters in a riverside storage warehouse and there it all stands. Forty-two years worth of my working life contained in rows of battered cardboard boxes, neatly stacked. I am possibly the only barrister to have kept pretty well every brief Ive undertaken. Originally just in case the notes and statements might be useful at some unknown future time for the purposes of another trial or appeal. And some have been.

But now its time to move on to a different future. Maybe some benevolent agency will adopt my archive. Meanwhile, I felt I should try to make some sense of the years Ive spent in the law. This book is an attempt to do just that. It may be on the large side, but then so am I! But always, my aim has been to keep an eye on the main point: justice being done, and being seen to be done.

Nothing stays still for long in the law. In the time that I have spent writing this memoir a number of the cases and issues I refer to have come back to life. Some have reached new conclusions, others remain unresolved, but the reader should know that the book he or she is about to read was up to date at the time of going to press!

Michael Mansfield, QC, 7 June 2009

Veins and Vanity

Camp Zeist in Holland. I am attending as an observer at the first Lockerbie appeal. My flights delayed; my taxi driver gets me lost; I rush to get in; securitys tight so tight that a burly police officer doing the body search, when rubbing up and down my legs, asks, Have you got something concealed in your trousers? I protest that there is nothing besides my legs, but the waiting queue is getting agitated so the police officer threatens a full strip-search in another room. The hearing has started. I cant stand queues or officialdom at the best of times. So I drop my trousers on the spot to reveal hard, bulbous, knotted varicose veins. This is a passport to a speedy entrance to the appeal.

Flashback to the late 1940s: Im one of three musketeers Jeremy, Robin and I are all about eight. I am thin and look a bit like William Brown from Just William grey flannel shorts, socks round my ankles and always a cap askew. We spend our free time roaming the wilds of north London and setting impossible challenges for each other. Normally these revolved around the rapids of what we thought was a vast river, but was in fact a rather turgid brook called Dollis, which runs from Barnet all the way through to the Thames somewhere near Chiswick. Little did I know that these challenges were to become a formative part of my psyche, because we each chose for another a task that tested our ability to face up to our weaknesses and fears. For example: wading through deep water, handling poisonous snakes, climbing gigantic trees and crawling through damp, dark tunnels. My particular fear was jumping from high branches, so when commanded to climb the tallest tree on the river bank, I reluctantly clambered up, but prevaricated for too long about taking the final leap. The two others decided I needed some encouragement. Suddenly I felt a sharp pain in the back of my right leg, and left the branch immediately. I had been shot by a German air pistol that my brother had brought back at the end of the Second World War, and which we regularly sneaked out from the garage where my mother had hidden it. The pellet penetrated my trousers and left a wound that caused a massive bruise.

Needless to say, I couldnt tell Mother how this was caused. She was forty-one when I was born in 1941, having had my two brothers Gerald and Ken in her early twenties. There was still the legacy of an earlier beauty discernible in her face and stature, although by this time she was distinctly portly. I inherited her large, pale-blue eyes. Mother was patient, kind and tolerant but, like so many women of her generation, paid due deference to my father. She kept a bamboo cane above the kitchen door in case of misdemeanours. She never used it, but threatened to tell your father if things went wrong. We both knew hed never catch me to cane me, as hed lost the whole of his left leg in the First World War, but I wasnt taking any chances over the air-pistol wound and eventually I suffered for my secrecy with varicose veins the size of drainpipes...

What happened to the other musketeers? Robin became an aerial photographer who worked on the Oscar-winning film Gandhi ; Jeremy pursued his love of all animals exotic and became a game warden in Tanzania.

As for me, my vanity got the better of me, after years of horrified glances at swimming pools and on beaches. Soliciting the advice of Mary, a friend who is a specialist in lumpy legs, I went for venous analysis at Charing Cross Hospital. This consisted of me standing stark naked, as Mary with roller in hand endeavoured to detect the extent of the damage to my arteries and the likelihood of deep-vein thrombosis. As she knelt in front of me, a passing colleague called out, Oh, Mary, same position, different man!

The consultation that followed with The Prof. began with a roving anecdotal discussion about the Old Bailey bombing in 1973 and other terrible events we had both experienced over the last twenty-five years in London, I as a lawyer, he as a doctor. I thought he was trying to prepare me for the worst amputation! Instead he was refreshingly candid about the shortcomings, imprecision and unpredictability of medical science. Having presented me with the pros and cons of the treatment then available, and because I wasnt in pain, he left the final choice to me. So I still have hideous legs.

From Finchley to Philosophy

It was a strange-looking bottle tall, narrow, square-shaped and according to the label, it contained Camp Coffee. I had discovered it in my favourite childhood retreat, the larder set into the wall beneath the stairs at 73 Naylor Road, and there could be no mistaking that it was number 73, as my father Frank had painstakingly carved the two numerals, in large relief, in the top of the privet hedge a few feet from our front door.

Our kitchen was what an estate agent would call conveniently compact, and my mother Marjorie always referred to it as the scullery. Yet somehow this tiny space managed to contain a large white enamel sink, a gas cooker that gave off more gas than rice puddings, and a bulbous silver American-style fridge, taller than me and adorned with an enormous metallic bronze handle. Stick four wheels on it and it might have passed for a Cadillac or a Buick.

Alongside that fridge was my haven, the recessed larder, shelved from floor to ceiling. Most of the shelves were empty, but there was always a small store of carefully preserved items, preciously obtained during that late-1940s era of ration books: a jar of homemade gooseberry jam from the allotments on the other side of the Northern Line at the bottom of our garden; packets of digestive biscuits; tins of corned beef, spam, sardines and condensed milk; sugar, tea and coffee.

Next page