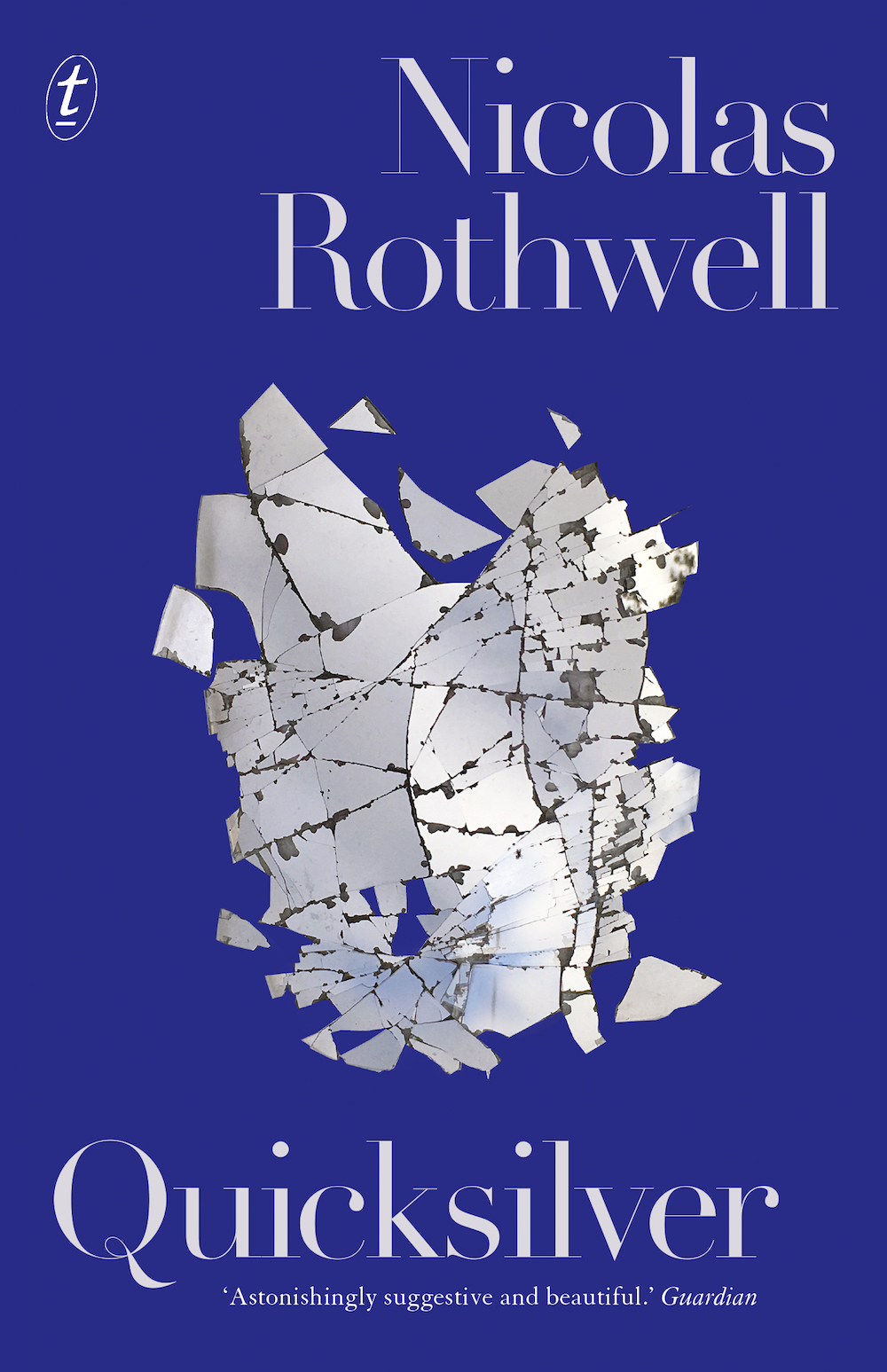

PRAISE FOR NICOLAS ROTHWELLS BELOMOR

I found myself completely captured by the lucid detachment and uncanny atmosphere of Nicolas Rothwells Belomor, four narratives that range from exquisitely shaped nuggets of art history to suggestive character studies of eccentrics and esoteric quests, and from European cities in the midst of destruction to the hidden world of the Australian bushYou feel as if imbibing too much at once might be awfully dangerous. Times Literary Supplement, Best Books 2013

[A] meditative journey through the empty ruins of the world, Nicolas Rothwells Belomor is by turns ravishing and dismaying, a novel which is also an essay on art and a chantepleure on meaning and impermanence. Australian Book Review, Best Books 2013

Beautiful and mesmerisingEngages the intellect as well as the emotions. Australian

This is a remarkable work, tinged with sadness and verging on poetry, tempered now and then with humour and authentic historical insight. It is a contemporary Australian novel of such beauty, its hard to find a precedent. Age

BewitchingA hymn of praise to the north and its inhabitants. Herald Sun

Rothwells considerable achievement is to provoke an emotional response to [his protagonists] philosophising. His gorgeous and fluid prose produces a sort of on-the-page hymn to life and death. Advertiser

Melancholy, singular, exhilarating, Belomor reads like a haunted history of the world. Delia Falconer

Nicolas Rothwell is the author of Heaven and Earth, Wings of the Kite-Hawk, Another Country, The Red Highway, Journeys to the Interior and Belomor.

nicolasrothwell.com

textpublishing.com.au

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright Nicolas Rothwell 2016

The moral right of Nicolas Rothwell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Abridged earlier versions of parts of this book appeared in The Best Australian Essays 2012, the Monthly, Meanjin and the Australian.

First published in 2016 by The Text Publishing Company

Design by W. H. Chong

Typeset by J & M Typesetting

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

ISBN: 9781925355574 (hardback)

ISBN: 9781925410006 (ebook)

Creator: Rothwell, Nicolas, author.

Title: Quicksilver / by Nicolas Rothwell.

Dewey Number: 919.41

In memory of Nyurapayia Nampitjinpa

CONTENTS

Be not wise in thine own eyes

It was the cold, dry midwinter season in the desert, when frost falls on the claypans; the skies are clear, and set the mind to roam. I began my days of journeying: I drove west from Papunya to Kintore and Kiwirrkurra, to Well 33 and on, past red dunes and salt lakes, past the ramparts of the Telfer goldmine, until the ranges of the Pilbara drew near, and I was almost within reach of my initial destination, Marble Bar. All through that crossing the country was quiet; the horizons were a transparent blue. There had been fires: the sandhill crests were bare. Bush turkeys stalked through the remnant spinifex, stretching out their necks and gazing fixedly towards the sun. The roads were empty: for the best part of a week I saw no trace of man and his works. It was a spectacle of solitudemuch like the landscape described by the first European explorer to make a successful transit of that country, the gloomy Colonel Warburton, whose uncommunicative eyes stare out from the frontispiece of his Journey Across the Western Interior of Australia, published in London in 1875.

Although Warburton and his men were the first outsiders to see the blood-red mesas and the open dune fields west of Lake Gregory, in his account of his expedition he pays scant attention to the features of the desert, concentrating instead on the privations his party endured in the course of their ten-month passage, as they laboured over the sandhills, slaughtering and devouring their pack camels one by one. By the last stage of the journey Warburton was full of anguish:

Night-work, tropical heat, no sleep, poor food and very limited allowance of water are, when combined, enough to reduce any mans strength; it is no wonder then that I can scarcely crawl. What a country! Did any men before traverse such a tract of desert? I think not.

In the end he fell so ill he could no longer sit in his saddle. He had to be tied full-length on the animals back, and so, trussed up like a piece of baggage, he proceeded until the dunes gave way to a range on the horizon, and then a rocky creek bed came into view. It led in turn to a wide sandy channel, lined by tall gumtreesthe Oakover, the great inland river of the northwest. The men made camp. They were within reach of safety. This must be a noble river, mused Warburton, when the floods come down. The bed is wide and gravelly, fringed with magnificent cajeput or paperbark trees. How grateful is its lovely and shady refuge from the burning sun after the frightful sand-hills in which we have been so long baked. The expeditions diet improved: a teal, small bush pheasants, a fish, a shag. Occasionally an iguana or cockatoo enlivens our fare.

Warburton moved his men to high ground. There were strong winds blowing round them, and heavy clouds went scudding across the sky. The weather cleared. The last camel was killed, skinned and cut up. That night his wish came true; the landscape showed them its other face:

To our great surprise we were awakened at 3 a.m. by the roaring of running water. The river was down, running with a current of about three knots an hour. In the evening there was not a drop of water in the riverin the morning a stream 300 yards wide was sweeping down with timber and ducks floating on it. The sight was most beautiful at sunrise.

Such, still, is the Oakover: relief after unending desert, the first gleaming flash of blue after the dunes and spinifex, tall fringing gumtrees, deep rock pools, curved, high embankments of river sand. I stopped. I got out of the four-wheel-drive and walkedalong the channel, up a side creek. It wound towards the hills. Its slopes steepened; it became a gorge line: a ravine. The sun was beating down; and at that moment I became aware of another presence, breathing, watchful, close at hand. There, right in front of me, was a large perentie lizard, unmoving, its forefeet stretched out in front of its body, its head held slightly up from the rock. Doubtless, I said to myself, a lineal descendant of one of the iguanas that had eased Colonel Warburtons recovery in this same stretch of landscape all those years ago. The creature gazed at me in solemn fashion, and made no attempt to move. Its forked tongue flicked out and back. Should I show any sign of having seen it? Should I make a gesture or a sound?

My thoughts flew at once to the most famous lizard anecdote in world literature: the tale of Leo Tolstoys meeting with a rather smaller species of lizard, a Black Sea gecko, which he encountered in Yalta, while walking along the road that leads up to the ornate Dulber Palace, a crenellated pleasure dome, built by Grand Duke Pyotr Nikolaevich just two decades before the revolution came. Maxim Gorky, the prince of proletarian writers, who revered Tolstoy as his exemplar in both art and life, describes the episode in the reminiscences he sketched out in his years of exile, marooned on Cape Sorrentoand perhaps it was the rhyme between the Mediterranean and the Crimean coastal landscapes that kept the incident so vivid in his thoughts. He narrates it in his most clipped and thrown-off style:

Next page