Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For TJD

Above all: to my travelling companions, John Boit, Ilya Suleymanov and Taran Davies.

Outside the Caucasus: to Irina Prentice and to her grandmother, Irina Bergmann, and their friend Marc Alexander. To Emilia Sherifova and her family; Marilyn Perry of the World Monuments Fund; John Richardson, formerly of Iridium; Bartle Bull; John Bruno of the Explorers Club. To Garo Keheyan and Sasha Abercorn for invaluable contacts.

In Azerbaijan: special thanks are owed to our two hosts, Dr Tim Bentley and George Noel-Clarke, who showed extraordinary patience to suffer through our comings and goings. Our trip could not have been the same without the help of Vahid Mustafayev and his company, Azerbaijan News Service (ANS). Not only did he provide us with our friend and driver Ramiz Norbalayev, but he also constantly surprised us with the lengths to which he would go to aid us. Many thanks to Vafa Guluzade for taking the time to meet us. Also to Kay Burn Lim, Don Churchman, Bill Reynolds, Jim Philipov, Rena Effendi, Professor Yaqub Mahmudlu, Zhura and Said, Ali Asaev and Fatima Aslan. To the Ambassador Stanley T. Escudero and his son, Alex Escudero; to Azad Dashdamirov, Fuad Akhundov and Suad Fataliyev.

In Armenia: many thanks to Ararat Sargsyan, his son Arshak and to his entire family, who treated us as their own during our stay in Armenia. There have never been better hosts. And thanks to their friends who showed great patience and warmth: Hovik Kochinian, Samvel Mkrtichian, Vartan Garoyan, Nazaret, Marina and Nare Karoyan, Marcos Grigorian and Saak Pogosyan. Also to Vartan Oskanian for taking the time to meet with us.

In Karabagh: thanks to Naira Melkoumian, Minister of Foreign Affairs.

In Georgia: special thanks are due to Marika Didebulidze, who went far beyond the call of duty in assisting us. Also to the Fund for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage of Georgia and to David Ninidze, Khaka Khimshiashvili, Yorgi Otkumezuri and Nino Bagrationi. To Irakli and Ketevan Sutidze, the finest of artists. To Professor Gocha Khundadze and Professor Mikhail Samsauadze of Tbilisi State University. For their openness and kindness, thanks to Gela Charkviani, Adviser to the President, and to Mamuka Areshidze, Head of the Commission on the relations with the People of Caucasia. To Vasha and Marina Chincharauli in Shateli. And warmest thanks to both Tamara Shamil and Merab Kokoshashvili who spoke so openly of their family histories.

Books: though a full bibliography is given elsewhere in Caucasus, I wish to acknowledge a special debt to Baddeley, Blanch and Lieven.

The city formerly known as Tiflis is always referred to by its modern name, Tbilisi.

Our journey to the Caucasus brought no definitive reward. We went in search of a legend and found it sometimes burnished, sometimes burning bright. We were trying to measure the effect one man can have on his regions history 150 years after his death. This figure, Shamil, was an Islamic mountain warrior leading diverse tribes against Russia. But in what way is a legend passed through generations? Why is he evoked, and when? Does anything of a man remain once he has become a myth?

These were all cloudy questions; and yet, during our journey in the summer of 1999, everything was suddenly jolted into focus. We had gone sniffing after a trail of bloodshed as old as man, and found ourselves witnessing the prelude of yet another round in one of the longest on-going conflicts in the world Russia against the mountains of the Caucasus. The past and the present, no matter how divergent they seemed at the beginning of our journey, were slowly being stitched together again. This, to me, is the effect of the Caucasus. I am not suggesting that the echo of history in the early twenty-first century is so precise that nineteenth-century differences have been erased, but the reverberations are considerable. I hope they justify covering old ground, if only to compare it to the new.

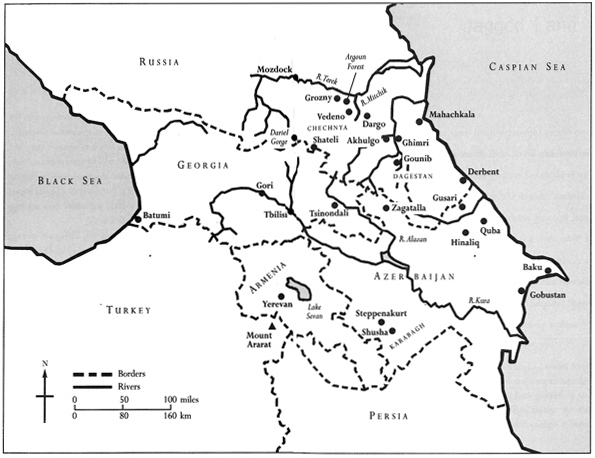

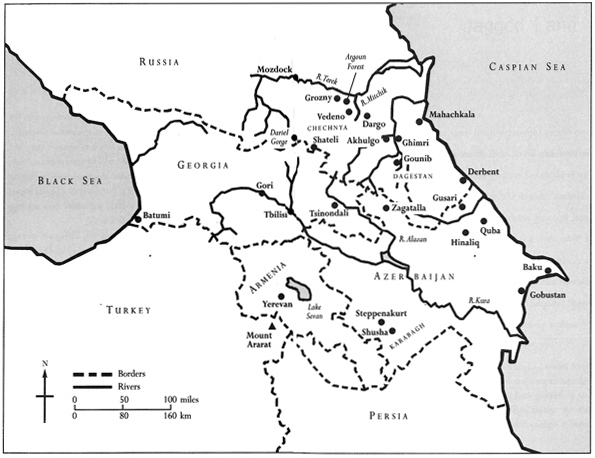

The Caucasus is a jagged land. Imagine powerful neighbours: Iran to the south, Russia to the north, Turkey to the west, hemmed by the Black Sea on one side and the Caspian Sea on the other. If the Caucasus didnt already possess the highest mountain range in Europe, the political pressure exerted from all sides would have forced the land to crack and rise. Now elect a conqueror. Genghis Khan, Alexander the Great, Tamerlane, a caravan of Persian kings, Peter the Great, Hitler, Stalin have all claimed conquest of the Caucasus. Choose a religion. Shiite Muslims to the south, Sunnis to the north; three schisms of Christianity push from separate fronts.

To attempt to unravel the history of the Caucasus would force the presumption that history would cease moving long enough for a considered look. Perhaps this would have been possible if the most recent conqueror of the region had been anyone but the Soviet Union, and though the Soviets were kind enough to leave behind enough power lines and vodka to keep people drinking deep into the night, they were not so direct with the histories of their satellite states. Soviet Russia did not hesitate to rewrite history, not just once, but repeatedly.

Even before the Soviets this was a land of myths and tales as tall as the peaks themselves. All Caucasians are great liars, said one of our hosts in the three competing countries of Transcaucasia. In Armenia, Noahs Ark lies on the borders. In Azerbaijan, the Garden of Eden is said to lurk somewhere in the south. Georgia is not to be outdone. If her neighbours boast of the genesis of man, Georgia claims to have been home to the gods. Prometheus was bound to one of her great peaks, his liver torn daily by the circling birds of prey.

Everything shifts in the Caucasus, blown by some of the strongest winds on earth. Even the ground moves, splintered by fault lines. In early Georgian myths, it is said that when the mountains were young, they had legs could walk from the edges of the oceans to the deserts, flirting with the low hills, shrouding them with soft clouds of love. History, of course, is the greatest shape-changer of them all. The further back you peer into the stories of the Caucasus, the more likely you are to be confounded by webs of contradiction and myth.

Head north in the Caucasus and the hordes of languages will confuse you. Imagine walking around the Eiffel Tower on a busy summers day and hearing the sounds of dozens of nationalities. Now imagine that no one has travelled more than fifty miles to get there. This is the problem: everybody is more or less at home and everybody is more or less in some kind of conflict. Not necessarily bloody, but often political, often territorial.

According to Brzezinski, Americas former National Security Adviser, there is no more important area in the world than the Caucasus. Geopolitically, it is the pivot about which everything sways: American economic interests, Russian territorial interests, Islamic religious interests, all factors in the oscillating local politics. It was considered just as critical 150 years ago, a narrow but vital bridge.