Table of Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

FOREWORD

Joyce Maynard

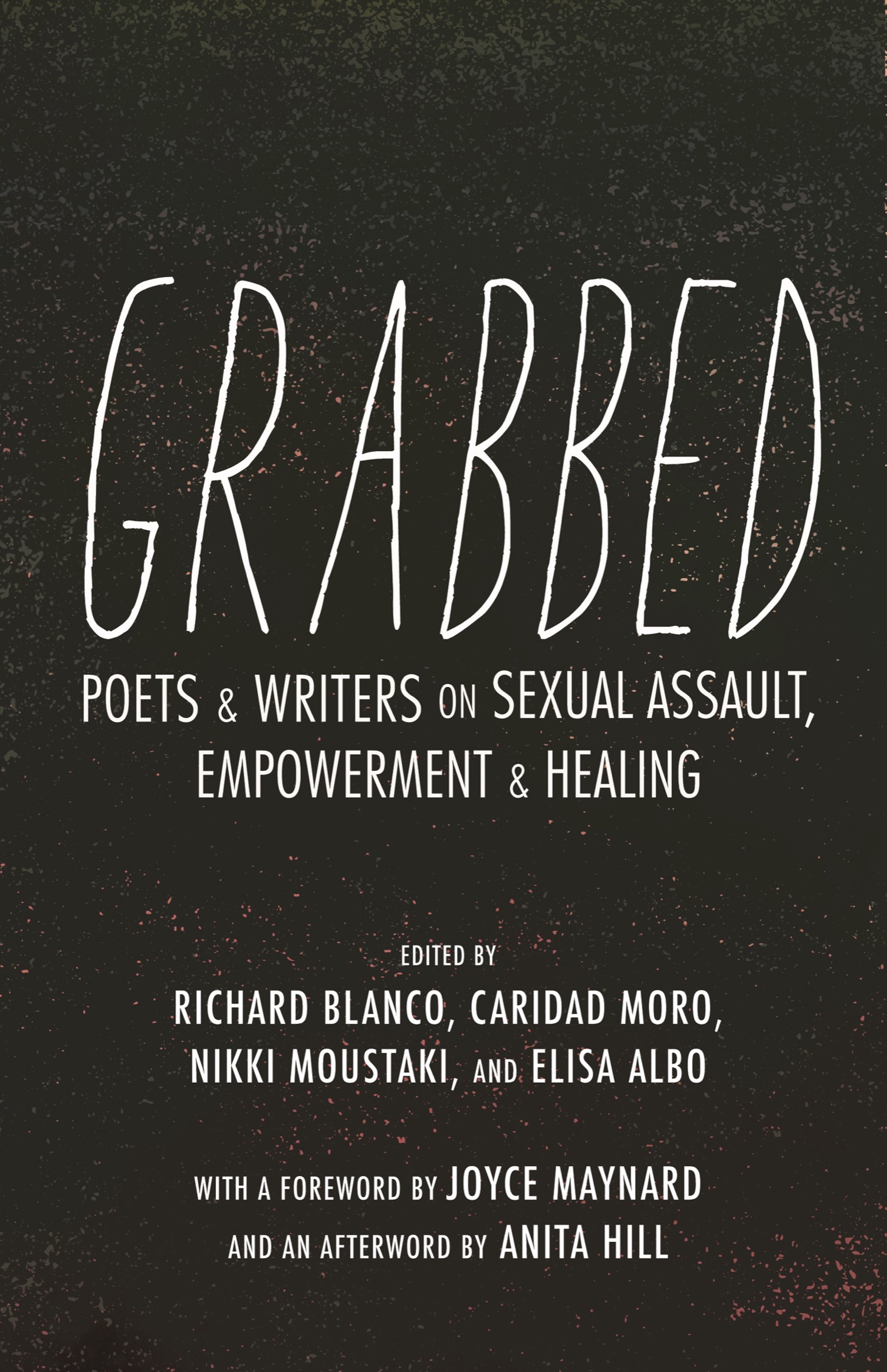

There are certain moments weve all lived through that take hold in our shared national consciousness. The explosion of the Challenger, the planes crashing into the Trade Towers, an immigrant mother holding the hand of her five-year-old as she flees the tear gas of the border patrol. One of those moments occurred when we heard the voice of Donald Trump, caught on tape proudly announcing to his buddy the perks of being a powerful man as they related to women.

You can grab them by the pussy, he said. You can do anything.

A month after that tape was played, again and again, on national television, our country elected that man presidentas clear an indication as a person might ask for that we had become a nation that condoned, and maybe even (like Trumps friend on the tape) chuckled over, violence against women.

But there is nothing funny in the stories and poems between these covers. Each one recounts a different and unique brand of painful experience. The element that runs through every one of them is clear: somebody touched somebody else in a way that represented a profound and painful violation. In one story, the predator reached out through the telephone line, but the place he grabbed hold of was as vulnerable as any: the authors brain.

What it tells a person, when someone touches another somewhere without consentwhether they grab your pussy or your butt or stick their tongue down your mouth on the way out the dooris that ones own body is fair game for anyone who wants to place their hands on it. That casual grab sends a powerful message: a persons body is there for the pleasure or amusement of the predator, for as long or as brief a time as it continues to amuse them.

Grabbed. Its an apt description. Were speaking about a kind of heist, not only of an individuals physical being but, very possibly, of her spirit. Or his. The stories collected herethough predominantly written by womenremind us that a man, particularly a very young one, can also be the prey. But heres the thing that distinguishes sexual predation from larceny: Stolen goods can be retrieved. Stolen innocence cannot.

And once a culture accepts grabbing the pussy as an acceptable activity, the culture itself is in jeopardy. When we normalize pussy-grabbing, or any other kind of grabbing, we are disrespecting our own fellow human beings and our own selves. (I would say here, we are becoming animals. But I like animals too much to put it that way. We are becoming monsters.)

The stories and poems in this book seek to remind us, grabbing is not normal. These stories stand as affirmation that our bodies are precious and sacred, and that touch still means something. And its effects linger. The writers here are offering up, with their stories, the most powerful negation of that stomach-turning Trump tape. One rich, entitled, and seemingly soulless man says its fine to grab. The authors of these stories and poems remind us, its not. Sexual abuse takes many forms. Sometimes the violation has been repeated many times, over years even. It may have taken place only once. Only once. But once is enough; the reverberations have endured into the present. Whatever it was that occurred, the fact that these writers have chosen to tell their stories stands as evidence that each is a different person for the experience of having been physically, or emotionally, grabbed. Every one of these writers lost something in that moment of violation. It is not retrievable.

I know about this because I am one such person myself. Almost fifty years have passed since my own experience of beingpsychically and then physicallygrabbed, when I was eighteen years old. I want to say that I did not let that experience define or crush me. But I am a different woman than I would have been had my first experience of sexual intimacy not been one of manipulation and intimidation. That experience provided my first glimpse of the landscape of sexuality and (these words are hard to write and harder to say) in certain ways colored it forever.

In my case, I name not one but two instances of life-altering violation, separated by twenty-five years. The first one happened when I was eighteen, when a much older and very powerful man came into my life and convinced me that his needs superseded my own. After hed discarded me, I lived for a surprisingly long time under the mistaken sense of obligation to keep his secrets, to protect him by, in effect, cutting out my own tongue. When, twenty-five years later, I finally located sufficient courage and sense of my own worth to tell the story of what had happened when I was young, I incurred a second brand of damage, possibly more painful even than the first. As a woman telling the story of an important man who sought her out as his sexual partner, I was labeled a leech, an exploiter, a big mouth, andthis, in the pages of the New York Timesa predator.

I am hardly alone, as a woman whorecounting the story of some form of abuse at the hands of a powerful manfinds herself the object of derision. Thats how it has gone, for as long as I can remember: Every time another woman has dared to tell her story, she risked a whole new form of violencerape in the court of public opinion. And here is a troubling phenomenon: contempt not only from men but too often from other women. Some of the harshest critics of the memoir in which I recounted my story were female writers. Misogyny is not the sole territory of men.

They may say it never really happened. Or that the woman to whom it happened must have been asking for it. They may say, of a woman who finally locates the courage to speak up, that shes looking for money, or fame, oras they did of meto sell books. They may just say the woman is a liar, or that she feels guilty about some sexual encounter she engaged in and seeks to rewrite history by suggesting that she didnt actually want it. If it really happened, why did it take her so long to speak up? goes the question, raised (invariably) by those who seek to cast doubt on the testimony of women who stand up and tell what happened to them when they were young.

Every time I hear this, I want to call out to the blandly dismissive pundit on the television screen: Maybe she waited because she knew there would be people like you, ready and eager to call her a liar. Maybe she waited, knowing that our world is filled with people seduced by power, money, and influence, who cannot believe that behind the steely-eyed face of the movie producer, under the well-cut business suit, behind the desk of the well-loved congressman, or the TV star, Americas favorite dad, might beat the heart of an abuser.

For as long as women have been touched, toyed with, drugged, raped, or grabbed, those same women have been dismissed and humiliated if they attempted to tell what happened. This has been the experience not only of the weak but of the strong. Anita Hill was one such woman when she testified at the confirmation hearing for the Supreme Court nomination of Clarence Thomas at proceedings that came to seem like her own trial. And lest we allow ourselves to suppose those days are all behind us, we must remember that much of the same treatment was directed at Dr. Christine Blasey Ford when she offered testimony of her experience at the hands of Brett Kavanaugh. Blaming the accuser was common practice twenty years ago, and it was alive and only marginally less flagrant in the fall of 2018.