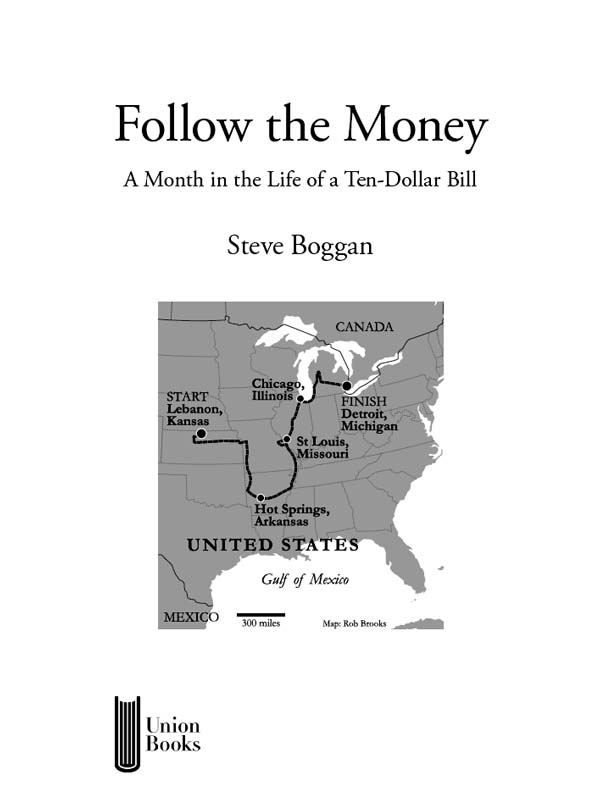

Follow the Money

For my father

S everal years ago, I took a phone call from Merope Mills, the recently appointed editor of the Guardians Weekend magazine. We had met briefly in her office a month earlier and I had been struck by her enthusiasm and her youth. She had the kind of energy and vitality that I vaguely remembered possessing once, a very long time ago. I had left feeling old and redundant. I doubted there was anything I could write that would appeal to her. At the time, my speciality was long and boring investigations that readers ignored and over which politicians often fell asleep.

I have an assignment for you, she said, but you dont have to take it...

I knew I didnt. Thats the whole point of being freelance. You choose what you do and, in return, you get to be poor and watch horse racing on TV. You are torn between wishing the phone would ring and disconnecting it. You spend too much time arranging lunch and convincing yourself that complete strangers with whom you get drunk could one day prove to be valuable contacts.

... because it might be impossible.

She had my attention.

I want you to try to follow a ten-pound note for as long as you can. Keep tabs on it and watch it as it moves. Write about where it goes and the people who get it. Do you think it can be done?

Instinctively, I knew who was behind this: Ian Katz. Katz was the editor of the Guardians Saturday edition, a handsome and clever workaholic who, in his previous incarnation as editor of the papers G2 features section, had landed in hot water for urging readers to try and persuade American voters in the marginal seat of Clark County, Ohio, to vote against George W. Bush in the 2004 presidential elections. Katz had bought a list of voters from the county for twenty-five dollars and suggested that Guardian readers write to those who described themselves as undecided, begging them to contribute to Dubyas demise. The project, called Operation Clark County, caused amusement in the UK, where it was regarded as a silly stunt, and uproar in Clark County, where people accused the Guardian of meddling where it had no business.

Katz finally pulled the plug on the exercise on 21 October 2004, after publishing a page of complaints under the headline: Dear Limey assholes. This letter was typical: Have you noticed that Americans dont give two shits what Europeans think of us? Each email someone gets from some arrogant Brit telling us why NOT to vote for George Bush is going to backfire, you stupid, yellow-toothed pansies... I dont give a rats ass if our election is going to have an effect on your worthless little life, I really dont...

According to the online current-affairs magazine Slate, this letter-writer was right about the stunt backfiring. Nowhere... did more votes move from the blue [Democrat] to the Red [Republican] than in Clark, wrote Slates Andy Bowers. In other words, the left-of-centre Guardian was responsible for a surge in right-of-centre voting. Bowers added, The Guardians Katz was quoted as saying it would be self-aggrandizing to claim Operation Clark County affected the election. Dont be so modest, Ian.

I always liked Katz. If this was one of his capers (and I later found out it was), then I wanted in. I just had to figure out a way to do it.

After a couple of hours, it occurred to me that the assignment need not be as complicated or chaotic as I had first assumed. A banknote is used to seal a transaction. The trick, then, was to get in the middle of each one before it happened and to take control of it. This, in turn, would require skill, energy, tact, patience, bonhomie and enthusiasm.

Not really my strong points.

But I did it. With photographer Richard Baker, I whizzed around a succession of bars in London, a dinner party in Islington where the note was used to sniff cocaine, onward to the Derby in Epsom, a golf club in West Sussex, through petrol stations in East Sussex, pubs in Hampshire and on to a market in Thame, Oxfordshire, where, on the seventh day, our ten-pound note serial number BE66 393677 was banked.

I was surprised not only by how interesting the exercise was, but also by how keen people were to co-operate with it and by how much fun it turned out to be, even when Baker insisted on telling each recipient of the note about his excruciating haemorrhoids.

There are only two types of person in this world, he would say. Those who have piles and those who are going to get them.

During moments when we were trying to persuade someone to let us follow them, this actually served as a bafflingly effective ice-breaker, and I suspect Baker nobodys fool knew it. At one point, we had been becalmed at a golf club for twenty-four hours; all the members had credit accounts and so nobody paid with cash. When, finally, the ten-pound note fell into the hands of some cash-paying day golfers, reluctant to help us, Baker won their confidence by coming over misty-eyed and declaring, Ive been dreaming of a long-distance lorry driver wholl take it up the A1.

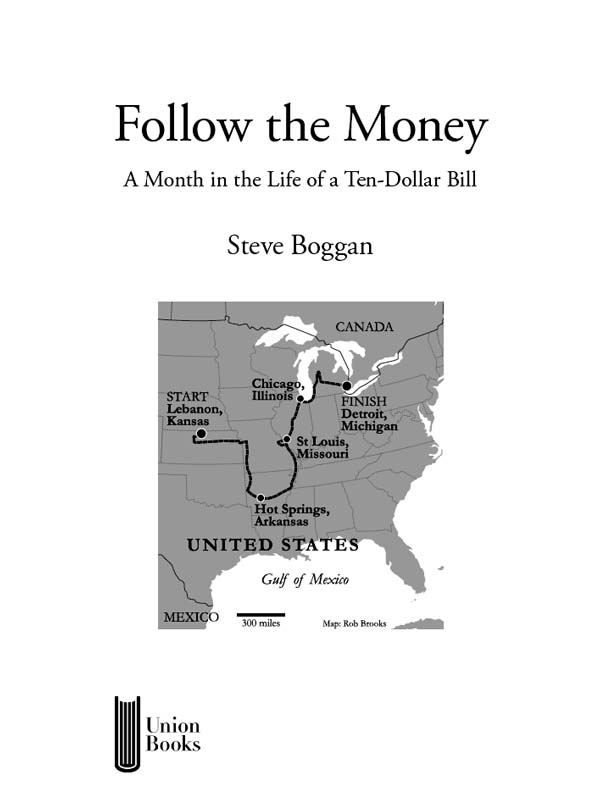

The ten-pound note project made me want to try something more ambitious. And once the seed was sown there was one idea I could not get out of my head: I would follow a ten-dollar bill around the United States of America for thirty days and thirty nights. Everyone I discussed it with agreed it was a terrific idea, but was it possible? Twice I set aside enough time to try, and just before starting out, I found excuses to cancel. This went on for almost half a decade. Finally, the excuses ran out and one late September morning I boarded a BA flight to New York. The following day I flew to Kansas City and on 1 October struck out for Lebanon, Kansas, to begin following the money.

Lebanon what?

Lebanon, Kansas. It was the obvious place to start.

(39 49.698' N, 098 34.769' W)

I n 1918 a group of scientists decided to find out exactly where the centre of the United States of America was. Locating the Center was something that Americans had, perhaps understandably, obsessed about for some time. The Founding Fathers had toyed with the idea of having the seat of government centrally located, while travellers thought it might be useful simply to know where they were in relation to the heart of their nation. Maps were not as accurate as they are today, but the group, employed by the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, had just produced one using the latest methods and they were confident that they could find an answer.

They didnt have to worry about Alaska way up to the west of Canada in the north or Hawaii 2,200 miles to the south-west in the Pacific Ocean; these states didnt join the Union until 1959. The cartographers and mathematicians had only to consider the Lower Forty-eight states, known variously as the contiguous, conterminous or continental USA.

Still, it was a tricky puzzle and one they decided to solve with a piece of cardboard, a sheet of tracing paper and a pin.

The scientists traced over their map, put the paper on to the cardboard, cut around the shape they had outlined and stuck the pin into the underside of the card until it balanced. When they replaced the map on top of the cardboard and pushed the pin through, they found their Center: Lebanon, Kansas, a tiny farming community located south of the Nebraskan border, about 220 miles west of Kansas City.

When I read about this piece of low-tech genius, Lebanon became, for a short time, the centre of my world too. As it happened, the Coast and Geodetic Survey regretted the exercise almost as soon as its scientists had carried it out because what they had found was the centre of gravity of the cardboard, and even the kindest observers pointed out that this could have been tens of miles off target in the real world. It was enough, however, for the people of Lebanon to establish the Hub Club to exploit and celebrate their new central status and, in June 1941, to unveil a monument and a motel one mile outside town at what visitors are still told is the geographical dead centre of the contiguous USA.