FOR HANNAH AND SARAH

IN THE HOPE THAT YOU WILL LIVE WITH amore.

DADDY

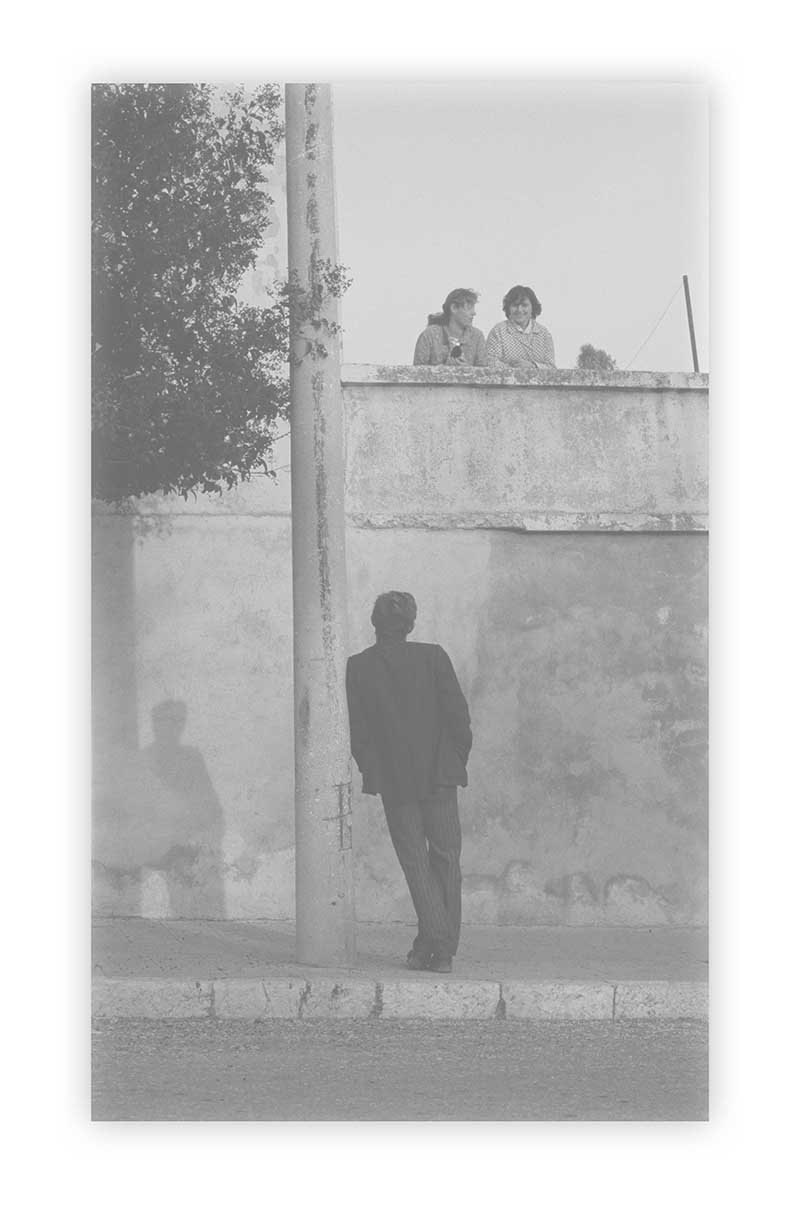

Granddaughter and grandmother at Villa Pamphili

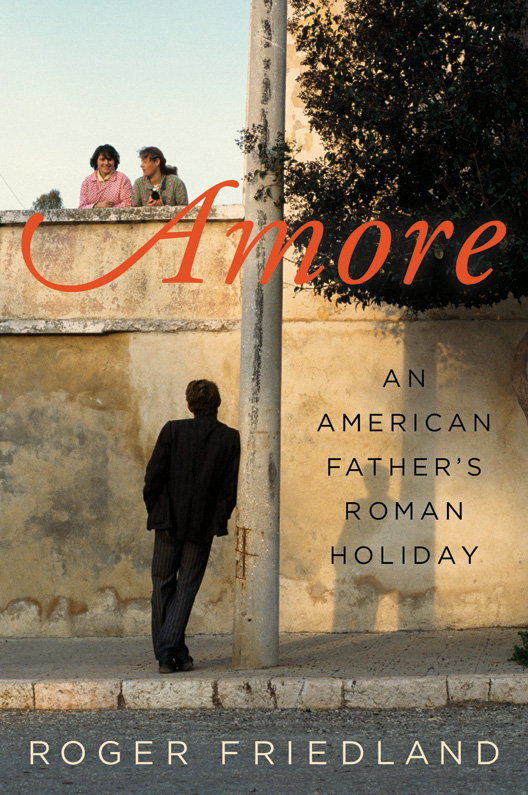

S OME MEN HAVE AFFAIRS with women. I fell in love with a city.

Rome, for me, is a beckoning love story, puzzling and paradoxical. I first came here decades ago, honeymooning with my wife, Debra. We talked and laughed; we broke beds; the oiled peppers slipped down our throats. We returned several times in the years that followed, hungry for escape and solace and a family of our own.

The children eventually did come. Years later, Debra and I returned here as our twin daughters entered their middle school years. As a father raising daughters in a culture where so many questioned the reality of romantic love, I wanted to understand this city where lovers nuzzling in public are as common as the stray cats that sleep on the warm marble slabs in the winter.

Coming from America, where sexual acts were increasingly unhinged from romantic love, their fusion in Rome fascinated me. The Romans, it seemed, still knew how to combine sex and love; Americans were losing the knack, and maybe even the desire, for it. The promise and pleasures of the erotic have proliferated at home, but they have become increasingly unmooredparticularly for young peoplefrom intimacy or commitment. Love, for many, is a story for suckers. Sex has become a subject of light banter, a snack on the buffet. We now even have twelve-step groups for those who want to wean themselves from the grinding routines of casual sex.

Passion persists in Rome. For the youth of the city, the fusion of sex and love is still viewed as an ideal state. This involves some apparent paradoxes: If anything, Roman culture is even more eroticized than our own. Yet love is not fading as a convention there; it has not become a silly rite, trite and hardly believable.

In Rome, sexual desire can infuse any encounter, between any man and any woman. Desire is a public good, a beneficent fact to be displayed, acknowledged, played with. It is part of making life beautiful. Roman women dont cover or bind themselves; they amplify their erotic allure, showing off their breasts, their bottoms, their legs. Women still dress and walk to turn a male eye. What American feminists would deride as sexual objectification is to them not a cultural crime, a betrayal of the sex. But Roman men, too, take care: They choose their colors, the sheen of their shoes, the cut of their hair, the way they walk and their faces open to the world, all to make themselves desirable, to be bello.

Yet Rome, this city of such intense erotic and romantic currents, also boasts the lowest divorce rate in Europe. Raising American children in a field strewn with broken vows, many of their friends raised by single parents, I could not help wondering: How do Roman mothers and fathers stay together at the dinner table in this flood tide of flirtation?

And then there is the God factor. In Rome, of course, the evidence and emissaries of Jesusand especially of Maryare everywhere. I had always thought of God, particularly the Christian deity, as an obstacle on the road to sexual pleasure, especially outside the bonds of matrimony. This is a city where cassocked men who have never had sex and wear scarlet silk stockings seek to regulate citizens sex lives. The Vatican has fought to prohibit divorce in Italy, as well as birth control, abortion, and assisted fertilization. Coming from a country where my fellow citizens increasingly invoke divine command as a political weapon to control other peoples sex lives, I wanted to understand how citizens whose neighbor is Vicar of Christ manage to maintain such romantic passion in their own lives.

Romes romantic landscape was alluring, but to me, at least, it didnt make sense. I was determined to figure it out.

T HIS IS AN A MERICAN fathers book of Roman love lessons. I have lived in many cities: Paris, Jerusalem, Dar es Salaam, London, Quertaro, Abu Dhabi, Los Angeles, Madison, Berkeley. But only Rome holds me, calling me back again and again.

The most important moments in my sentimental education are bound up with this place. Eight years into our marriage, after our fathers died within months of each other, Debra and I returned to the site of our honeymoon; we mourned here, and it was here that Debra fiercely decided to keep trying to have a baby after years of infertility. Not long after that, we received our greatest gift: twin daughters. When Hannah and Sarah reached their third birthday we brought them to Rome for a year, wobbling into a Montessori nursery school on the Aventine, one of Romes fabled seven hills, where the citys founding twins, Romulus and Remus, fought over which of them was truly favored by the gods.

The city moves me; she is my walking cure. When we are here, Debra and I walk the pine-lined dirt pathways of Villa Pamphili, once a noble estate given by the pope. The citys walls are creamy slabs saturated with clear winter light; sometimes I feel I could almost lick them. On the weekends, in the late morning, we watch the citys streets fill with children feeding ducks and pigeons, their small hands holding those of their parents or grandparents, not those of maids and nannies, as in Los Angeles. At the citys energetic corners, where anticipations accumulate, young women in high heels pause on their motorini , flashing olive-skinned thighs as they wait for the light to change. The mothers address their little ones as amore.

I AM NOT ONLY a father, but also a professor of cultural sociology and religion at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where I teach courses on sex, love, and God. When Hannah and Sarah were thirteen years old, I was invited to spend two years teaching students at the University of Rome. It was a welcome opportunity to return to the city I love, and to compare young loves and carnal passions across two continents. Hannah and Sarah would come of age in its piazzas, getting their periods, negotiating the idea of a first kiss, worrying what dress to wear for a dance.

When we announced that we would be moving to Rome, Hannah was excited. She loved fashion and jewels, designed wedding dresses on kitchen notepads, inhabited multiple worlds in the novels she consumed like afternoon candies. Hannah spun ebullient webs of words, wrote poetry, loved talking to everyone she met to try their worlds on for size. She remembered the Italians from childhood, knew they were passionate chatterers like her. At soccer games, Hannah would engage the midfielders from the opposing team in conversation, oblivious as the ball rolled by behind her.

Sarah, on the other hand, began to sob. As a little girl, Sarah had clung to her mothers skirt, gazed back at us with pleading looks as we left her at the school gate. Sarah didnt talk; she watched and listened, storing up secret images and opinions. What touched her werent words, but images, sounds, and movements. She loved to dance, to compose music, to devour movies with her mother. She didnt say much, but she saw and felt everything. We were taking her familiar world away from her.

I pined for the citys strange magic, for myself but also, I imagined, for our daughters. Junior high school, our American friends warned us, was a miserable age, especially for girls. Indeed, Maria Montessori, who began her educational experiments with working-class Roman children, thought schooling in those years was useless. It would be better, she thought, to send children out to the countryside to work.