acknowledgments

_______

When I began writing this book, I had what I thought was a novel idea: write only about the dogs and leave people on the sidelines completely. I quickly discovered that this was impossible. To tell the dogs storiesor even my ownrequired a cast of humans. Which is as it should be. But there wasnt room for everyone, so I hope to fit them in here:

Ann Treistman, and everyone at The Lyons Press.

In New York: Sharyn Rosenblum, Ben Neihart, Terese Svoboda, BARC, Stacey Alldredge, Catherine Texier, Emily Twomey and Jamie, Garrett Rosso, Java, Jill Bossert, and everyone at the dog run. Well, almost everyone.

In Florida: Lisa Collins, Debbie Geiger, Pam Houmere, Cynie Cory, Tom Kay, Jennifer Westfield, Jeremiah Tash, Victoria Winterling, Bob and Catfish, Lisa Lambert, Mark Winegardner, Jimmy Kimbrell, Spurgeon and Sandy, James and Gaelynn, Trish and Eric Hanson, Liz Joyner, Janeen Wallace, Bridgitte Byrd, Westwood Animal Hospital, Kathy Connor, Judy Suplee, and Case Miller.

In Mississippi: Everyone at the Southern Heart Center and the Center for Writers, particularly Rick Barthelme, Steve, Angela, Rie, and Melanie; Martina Sciolino, Allison Campbell, Travis Kurowski, Jay Todd, Ben Butler, Britt Haraway, and Case Miller.

In Louisiana: the Louisiana SPCA, Faulkner House, Anne Gisleson, Brad Benischek, Silas, Julia Lane, Brad Richard, Andy Young, Deborah Choate, Lisa Robinson, and Case Miller.

Thanks also to the PEN American Writers Fund, the New York Foundation for the Arts, and the Wesleyan Writers conference. And my family.

how they find me

_______

DOGS ARE LIKE TATTOOS.

Ask folks about their tattoos and they can tell you exactly what was going on in their lives when they got them, how the idea came to them, why it seemed, at the time, a good thing to do. Even if they had lightning bolts tattooed down their face, to hear them talk about it you realize tattoos are a sentimental art. They mark their owners permanently with a visual memorial of the past. Like dogs do.

Ive never had a tattoo, but Ive had many dogs, and all of them have left their own indelible marks on me.

Ive found dogs tied under park benches.

Stuck in drainage grates.

Running door to door in the neighborhood with half an eye out.

Ive even had a dog delivered to me by police escort when her owners were involved in a domestic dispute.

Ive found dogs listed online and placed listings for other dogs to find a home of their ownthe dog equivalent of Internet dating.

Ive delayed vacations by stopping to pick up a stray dog along the road.

My friends think I must go looking for them. Didnt you just find one last week? Do people bring them to your house?

I tell my friends they dont let themselves see them, because then they would have to do something, too. People ignore stray dogs the same way they ignore stray people, the way your friends in the city insist that they have never seen any homeless people or, when pressed, offer the opinion that these people choose to be on the street and wouldnt want a home if they had one.

I was driving down a Mississippi road with Case, one of my blind-to-dog friends, and spotted a dog on the horizon, wandering down the middle of the road, coming toward us as we sped along in my friends truck. I let out a sigh.

What? Case asked. He may not see dogs, but you cant sigh around him without explaining yourself.

I nodded in the direction of the dog. Case, who was driving, still didnt see anything.

The dog, I said. We were speeding ever closer, and the dog was still coming toward us. A badly matched game of chicken.

What dog?

Right there! I yelled, pointing at the windshield.

Oh him, Case said. Hes always there.

They find me. It isnt ever the other way around. I dont go marching into overgrown patches looking for dogs who dont even know that they are lost. I dont carry a net in my car that I can toss great distances. What happens instead is this: They come up to me and sit at my feet. They tap me with a paw. They loiter in my path waiting for someone to do something. They cant talk. They cant make signs. There is a limit to how much they can tell us.

We are supposedly smarter than they are, but clearly not more intuitive. If we had their skills for assessing a situation I would never see this: car after car swerving to avoid two dachshunds wandering the middle of a highway. Most not even slowing down.

Rescuing something takes time, and there is a risk of revealing something about yourselfyour vulnerabilitythat isnt fashionable at all.

Thats what people dont understand. You do it because it is difficult. You do it because you arent sure of things. You do it without knowing how any of it will turn out, or how much it will cost you, or if the story will be happy or tragic in the end.

on being rescued

_______

IN AUGUST 2001 MY PARENTS DROVE INTO MANHATTAN to pick up my dog and me for a trip home to Pennsylvania. Earlier that yearmomentarily mortified at my decision to get an animalthey had vowed that my dog Brando and I would never be allowed in their home, but it was only a few weeks later that they broke down. This was typical of my parents. They felt getting a dog was a huge error in judgment, but once it was clear that my mind was made up on the subject, they wanted to be a part of the mistake.

Brando was still a puppy, although a huge one. At sixty pounds he had just begun to lift his leg to pee, and earlier that day he marked each of the entrances to Tompkins Square, as if he knew he wouldnt be seeing it for a while. He had traveled home often enough that he thought any white van was my parents white van, and he would sit down on the sidewalk waiting for a door to open so he could hop inside. He was stubborn and had otherwise always been reluctant to go anywhere, as if he feared being left behind, but once he had decided to trust peopleneighbors, the staff of the hot dog store down the streethe was obsessive about hunting them down. Sometimes, when he had parked himself on a street corner waiting for someone he had seen there the day before, the only way of getting him to move was to carry him, which I did frequently until he reached fifty pounds. My indulgence only made things worse, although it may have been inevitable that he would develop separation anxiety once I had rescued himand having rescued him, I was willing to put up with any problem he might have in the future.

On this particular trip my parents were also picking up Laurelan old friend, my babysitter when I was younger, and the daughter of a neighbor back home in Pennsylvania in our little one-road town. In New York City she lived just two blocks away, closer, perhaps, than she had back home. Brando thought the more people, the better, but still managed to settle into his spot between my parents bucket seats once the car started moving. We anticipated a long trip, a four-hour drive with plenty of bathroom breaks for the dog. We were trying to decide on the fastest way out of townsouth to the tunnel or north to the bridgewhen the car died in the middle of Great Jones Street near Lafayette. The drivers behind us responded instantly with honking horns. I ran out to the service station on the corner, where I was told that it would be several days before they could look at it.

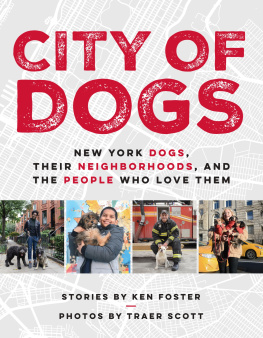

It was Laurels idea to go to the fire station. The men came out of Ladder 9/Engine 33 and helped push the car to the side. They brought out water for Brando while we stood outside in the excruciating summer heat. They walked a block farther to another service station, and the owners agreed to fix the car immediately. Laurel and I joined a couple of the men to help push the car down the street, and Brando helped, too, putting his paws up on the back of the van as we pushed. He had no idea what we were doing, of course. He just wanted to be near me and involved with the other men.