Table of Contents

To my three ladies: Lisa, Hannah, and Sarah.

And with great thanks and appreciation to

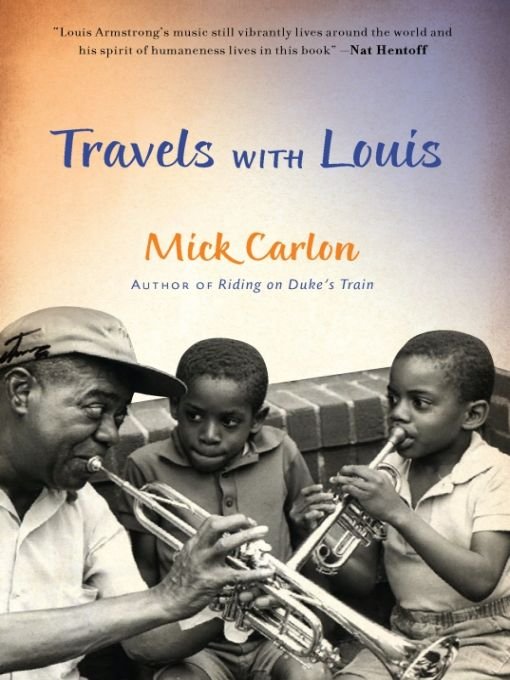

Jack Bradley, Nat Hentoff, and Brian Morton.

Thanks, lads!

One

Corona, Queens: Early August 1959. Dusk drenched in summer shadows. A baseball diamond in the neighborhood. Old Mrs. Fontaine calling for one of her cats. Soft front-stoop voices and the bells of a Good Humor Ice Cream truck.

Since the boys who played ball daily on this field were only twelve years old, no windows had yet been shattered.

Its too dark, said Fred. I cant see the ball anymore.

Aw! scoffed Mark. Our Freddie just wants to run home and play his little horn.

You dont see Willie Mays playing no horn, said Steve, sprawling in the grass behind the pitchers mound.

Fred grinned. He knew his friends envied his musical talentand his trumpet teacher.

Whens Louis getting home? asked Mark, a husky boy with enormous eyes.

Next week sometime, said Fred.

Whered he go to this time?

Africa.

Oh, manimagine that! said Steve.

Man, Id love to go there! said Mark.

And see all those ladies wearing no shirts! said Fred.

Aaaaaaawwww!

Their hands behind their heads, the three boys stared up at the dusky purple sky. Mothers were calling in the little ones and the sounds of radios and televisions spilled out from the nearby homes.

My dad says that when he was a kid, Louis Armstrong was it, said Steve. That Pops was the cleanest, sharpest dude anywhere. He said that you bought his records the second those babies came out.

Fred smiled with pride. For a moment no one spoke.

Anyone have any money?

Yeah, said Steve. I have a buck fifty left over from my birthday.

Lets go to Fat Petes, said Fred, leaping up. Steve, my man, youre treating us to some ice cream.

As a jet from LaGuardia Airport headed out across the Atlantic, the three friends dashed off to Fat Petes Ice Cream Parlor.

Two

Is that you, son? asked Big Fred from the living room. Only the lamp standing behind his favorite chair lit the room. A pile of newspapers lay at his feet and some jazz played softly on the radio.

Yeah, Dad.

Theres a postcard for you on the kitchen table.

On the postcard two gazelles were sprinting across the African plain. The back was covered with Louis curlicued handwriting. As he climbed the stairs to his bedroom, Little Fred read:

Brother Fred:

Im playing my horn for the people and theyre giving old Pops back plenty of love. Speaking of love, Miss Lucille and I are sending you and your dad plenty from across the seas! See you soon! Red Beans & Ricely Yours,

Louis

P.S. Now save some of that good old Fat Petes ice cream for me, you hear?

From beneath his bed Fred pulled the shoebox that held all of Louis postcards. You name the cityParis, London, Rome, Boise, Rio de Janeiro, Hyannis, Mexico City, Milwaukee, Montreal, Providence, VeniceLouis had played them all. To his collection Fred added the galloping gazelles.

A battered old trumpeta horn that had belonged to his grandfatherstood waiting on the night table. Not a day passed without Fred practicing his music. A warm breeze was stirring the curtains. Standing by the window, he blew some soft, sad, sighing blues. To Fred, this was the only reason to play music: to release his feelings, to let out his emotions, whether they were Friday afternoon joyous or Monday morning lowdown.

A knock on the door.

Come in.

His father entered. Since his wifes death three years before, Big Fred tried every day to be there for his son. Yet he also knew when to give the boy his space. Along with playing music, Little Freds happiest times were spent playing catch in the evenings with his father.

Sounds good, son, real good. You sure can play them blues. He sat down on the end of the bed.

Thanks. A question occurred to the boy. Dad, why is Louis so good to us?

Big Fred smiled his warm, gap-toothed smile. Because a long time ago Louis and your grandfathermy fatherwere dear friends. They played music together all over New Orleans and then in the summers they played on those riverboats that chug up and down the Mississippi.

Sometimes he looks so sad, thought Little Fred. Always remember that he misses her, too. Youre not the only one. He looked over at his hornbattered, bruised, and tarnished in the lamplight. For a moment he pictured it in the hands of his grandfathera man he had never knownin a sweltering dance hall in 1918 New Orleans. Lovely ladies swayed in front of the bandstand, their reflections captured in the horns bell.

How come you never played? he asked his father. Why did you give it to me?

His father smiled. Some people are born with certain talents and some people arent. Im in the last category as far as music goes. I triedbut I just didnt have it. You, on the other hand, have a true talent, son. Its a pleasure when Im downstairs reading the papers and I hear you playing. It s better than the radio these days.

Remember how they would laugh together in the living room? Now all he does is read at night. Some Saturday nights he even forgets that Gunsmoke is on.

How old were you when Grandpa died? asked Little Fred.

As old as you are nowtwelve.

Youve never told me what he died of.

Big Fred took a deep breath. Thats because I felt you werent old enough yet to know. But youre growing up into a thoughtful young man. Dont think I havent noticed. Another deep breath. You ever notice how I dont touch alcohol? The boy nodded. That s because I saw it kill my father. I saw how alcohol poisoned his relations with my mother, how it smothered his music.

He died from drinking?

Yesand I swore to myself as a boy that I wouldnt let alcohol ruin my life, too.

Father and son were quiet. In the distance a siren wailed.

And thats when Louis stepped up to the plate. God knows he didnt have to. He and my father had been out of touch for years. But Pops took a genuine interest in my mother and me. Every month a check would arrive in the mail to pay for our rent and groceries. And then when I turned sixteen he began taking me out on the road with his band in the summers. Paid me ridiculous amounts of money to simply set up some microphones. The rest of the time I explored foreign cities and listened to Louis music. I couldnt believe the money he paid me. Id mail most of it back to my mother. I dont know where Id be without that man. Big Fred gently squeezed the back of the boys neck. You know he loves you like a grandson. You should see his eyes light up when he sees my fathers old horn in your hands.

But Louis eyes are always lit up, said Little Fred.

His father laughed. Thats so! Cant deny that. Some folks are born geniuses and others are born nobility. Pops is both. Good night, son. I love you.

Love you, too, Dad.

Little Fred played his grandfathers horn for at least an hour before he fell asleep. Downstairs his father read his newspapers and enjoyed the music.

Three

On this steamy August night the drone of crickets nearly drowned out the distant sounds of car-horns and sirens. Little Fred and his father sat reading in the living room, a recording of Louis Armstrongs Hot Fives playing softly on the phonograph. On the last day of school the boys English teacher, Mr. Kendall, had given him a hard-cover copy of Richard Wright s autobiography,