To the players and fans who gave me their time and stories, to Rachel and Elias, who lost their voices with me at the Uruguay match, and to Aviva, for her endless faith.

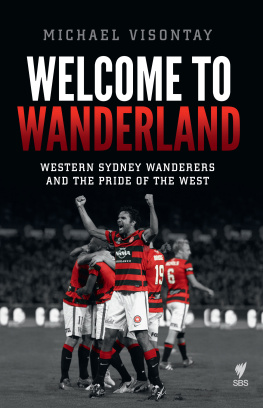

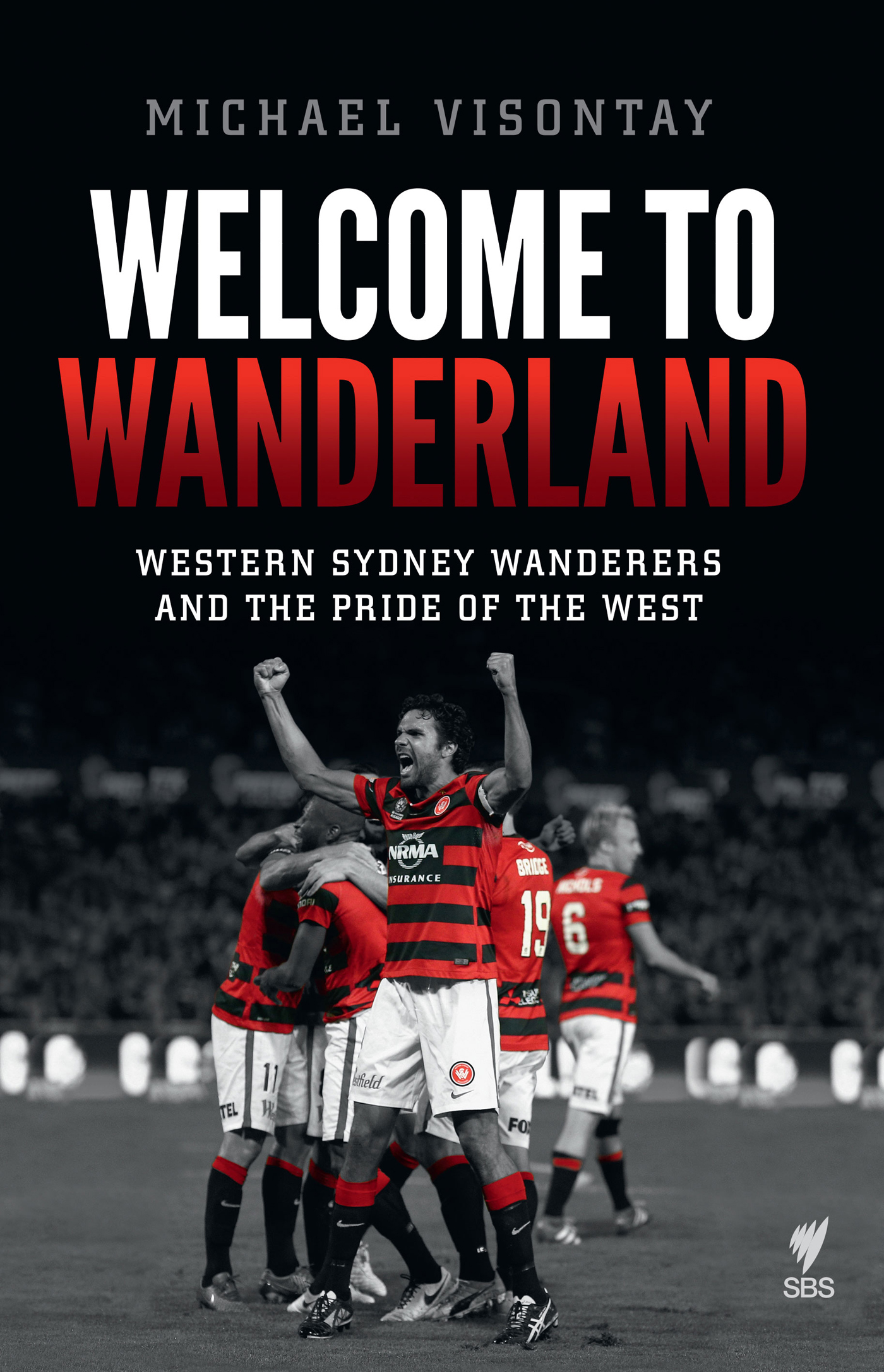

Were all familiar with the tale of Western Sydney Wanderers by now. Of Popa, Shinji Ono, that night in Riyadh, the Grand Finals, the Premiership win in Newcastle, the RBB and the Poznan.

What few of us know, is the back story that brought about all those names, events, stories and spectacles. Michaels book brings to life the birth of the Wanderers, how it brought together a disparate community, and gave identity to an often marginalizedor ignoredpart of Australias picture-postcard city.

Western Sydney Wanderers have only been with us for four years, which seems scarcely believable after all theyve achieved. But the Wanderers name has been deeply ingrained in the psyche of Australian football fans, ever since a round ball was first kicked on Parramatta Common, back in 1880. It seems this club was the one everyone had been waiting for, all those years.

By 2080, Im willing to bet the Wanderers will be at least twice its current sizeand the honours list will have been added to, many times over.

Its not too difficult to predict that this historical record of those vital early days, will also stand the test of time.

By then it should be sitting dog-eared, sepia-tinged, but cherished as an important reference, on supporters bookshelves, all over Western Sydney and beyond.

Simon Hill, Foxtel football commentator

CONTENTS

It was a scene unimaginable even five years ago. In the early hours of a November morning in 2014, while the sky was still dark and most Australians were fast asleep, a steady stream of people started making their way to Centenary Square in the heart of Parramatta in Sydneys west. They were all ages, size and shapes and they were all dressed in the same colours: red and black. They trickled into the open space, keen to get close to the giant television screen that was mounted there to show the second leg of the Asian Club League final being played in a few hours in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on the other side of the world.

Soon the trickle swelled into a substantial crowd, flags and banners everywhere, and by kick-off, just before the sun rose in the Sydney sky, Centenary Square was packed with up to 5000 fans, every one of them bursting with nerves and excitement as they waited for their team, the Western Sydney Wanderers, to do battle with the Saudi champions, Al-Hilal, for the biggest prize in Asian club football.

Over the next two hours, they watched with anxiety and pride as the Wanderers battled for gloryfor the title of Asias best clubin the name of western Sydney, against a team backed by money and resources that drew players from all over the world. Every so often, the crowd groaned and cheered at brave tackles, fans instinctively turned and grabbed the person next to them at what felt like a tidal wave of near misses by the Saudi team.

In the intensity of this one, prolonged moment of passion, it was easy to forget the larger significance of the gathering. This was about much more than football. The heaving and chanting of so many people coming together, arm in arm, shouted a message about Sydneys west, which had languished for generations under the mantle of black sheep of Australias middle-class psyche.

In two short years, since their foundation in late 2012, the Wanderers created something that decades of urban planning, government policy and arts handouts have failed to achieve. Even as years of property booms turned pockets of the west into extremely expensive real estate, it was forever in the shadow of the communities to the east and north, defined by what it was not, rather than what it was.

The Wanderers have given western Sydney a coherent identity, a status that has unified the rich multicultural heartland out there into a standard-bearer for Australian sport and community spirit. They have redefined what the west is, geographically, culturally and psychologically, and they have given the residents of this part of Australia a new voice through which to feel and express their pride about where they live.

Its a civic pride they have known and shared among their own communities for many years, built on the cultural tapestry, space and no-nonsense attitude that has grown out of the diverse lifestyles in the west, and enhanced by years of condescension from inner-city media.

Anyone who has been in the centre of Parramatta on match day for the Wanderers has seen this civic pride translated into a buzz and excitement without parallel in Australian sport. Not even the most ardent of Australian Rules football fans transform their local neighbourhood as do the Wanderers, especially now that most matches in Melbourne have been moved to the MCG. But game day is more than the tribal procession led by the Red and Black Bloc (RBB) from the Collector Hotel. Its a mosaic filled by families walking happily on their own, parents and young children, groups of young women, as well as the young men who constitute footballs core support base. Walking around Church, George and OConnell streets on a sunny summer afternoon, you cant help but be touched by the sense of communal family, greater even than the common cause, that envelops the area.

As kick-off approaches, the RBB marches down to Pirtek (Parramatta) Stadium. In the early days, they gathered at the smaller Woolpack Hotel at noon to drink, sing and chant for a game that would start seven hours later. After that they met at the Roxy Hotel, until it was closed down, and nowadays, they leave the larger Collector Hotel and march down Church Street through Prince Alfred Park, a sea of red and black and thumping drums that grows louder in front of fans faces lining the streets on their way to Parramatta (officially known as Pirtek) Stadium.

The march is not unique to Wanderers. Its a tradition among A-League clubs, imported from the great clubs of Europe and South America. But its not part of Rugby League culture so it is new for western Sydney, which endows it with a sense of intimacy. In comparison to Sydney FCs Cove march from South Dowling Street to Allianz Stadium through the teeming traffic and public arteries of Moore Park, the RBB marchthrough the local streets that people work and live inreflects a communal centre of gravity. This is our place, our turf.

Where do these supporters come from? Who is a Wanderers supporter? The answers are more varied than I had expected when I set out to write this book. Despite the legacy of ethnically based clubs in the community, fans are drawn from far and wide. A love of football, nurtured by family or school, is certainly a core factor but equally influential is a latent pride in the community, which the Wanderers have been able to ignite into a devoted membership.

There are fans who follow other football codes at the same time but find something special in the passion behind the Wanderers; there are those who were never interested in football, were taken to a game and became part of the cause; there are yet others who followed Sydney FC because they loved football but never felt FC represented them properly. Some live on the north shore of Sydney or the east but identify with the Wanderers because the club resonates with their own upbringing in other countries. Then there are fans who followed the European leagues, and the Socceroos, but did not feel the old NSL spoke to them, fans who felt that authentic football culture lay elsewhere, anywhere but hereuntil the Wanderers made them feel that football in Australia could be the real thing. Their stories are what gives the club its mojo. They give flesh to an idea, more than thata cause, that languished for so long as an assortment of uncollected yearnings.