In the Shadow of Wounded Knee

THEODORE ROOSEVELT IN THE BADLANDS

A YOUNG POLITICIANS QUEST FOR RECOVERY IN THE AMERICAN WEST

ROGER L. DI SILVESTRO

Bloomsbury USA

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

1385 Broadway

New York

NY 10018

USA | 50 Bedford Square

London

WC1B 3DP

UK |

www.bloomsbury.com

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2011

This electronic edition published 2011

Roger L. Di Silvestro, 2011

In quoting text from historic documents, all original spellings were preserved. Very minor and only occasional alterations were made to grammar and punctuation and only for the sake of clarity.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

ISBN: ePub: 978-0-8027-7845-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Di Silvestro, Roger L.

Theodore Roosevelt in the Badlands : a young politicians quest for recovery in the American West /

Roger L. Di Silvestro. 1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-8027-7845-1 (e-book)

1. Roosevelt, Theodore, 18581919Homes and hauntsNorth DakotaBadlands. 2. PresidentsUnited StatesBiography. 3. Frontier and pioneer lifeNorth DakotaBadlands. 4. Ranch lifeNorth DakotaBadlandsHistory19th century. 5. Badlands (N.D.)Biography. I. Title.

E757.D585 2010

973.911092dc22

2010044287

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events, and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Bloomsbury books may be purchased for business or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases please contact Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at .

FOR MAUDE AND KEN,

who introduced me to Americas true West

and left me with countless fond memories

AND WITH THOUGHTS OF MY FATHER,

who first introduced me

to the life of Theodore Roosevelt

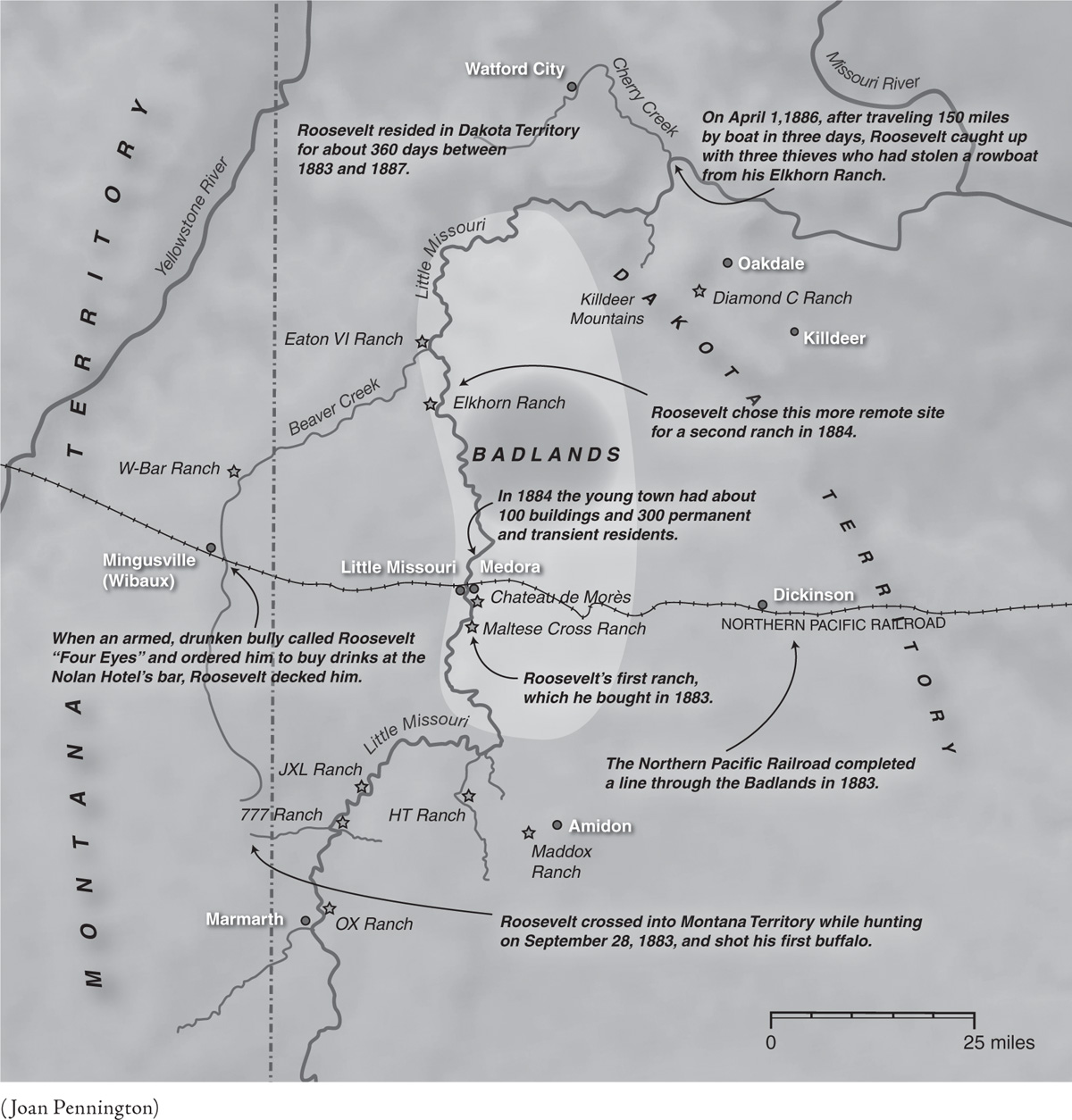

Although he was more a tourist and outside investor in the West than a permanent resident, Roosevelt and the West is one of Americas great stories. His sojourns in the Dakotas, Montana, and Wyoming had a powerful influence on his outlook and politics. Most of all, his time in the West brought him great joy.

STEPHEN E. AMBROSE,

introduction to Hunting Trips of a Ranchman and The Wilderness Hunter

It rains here when it rains an its hot here when its hot,

The real folks is real folks which city folks is not.

The dark is as the dark was before the stars was made;

The sun is as the sun was before God thought of shade;

An the prairie an the butte-tops an the long winds, when they blow,

Is like the things what Adam knew on his birthday, long ago.

From Medora Nights

CONTENTS

MORE YEARS AGO THAN I CARE TO RECALL, WHEN I WAS SIXTEEN, A family in the Nebraska Sandhills invited me for an extended summer stay on their cattle ranch, a spread of some six thousand acres of grassland grazed by two thousand Black Angus cattle, a handful of Texas longhorns, and several dozen quarter horses. The ranch lay about thirty-five miles from the nearest town, a compact village of tree-shrouded houses and one- or two-story buildings that was home to 810 residents.

Only dirt roadsactually, roads of the grayish white sand that gave the region its nameled from the town to the ranch, and at least half of those roads were just dual tire tracks cutting across a minimalist landscape of empty, rolling green hills under a generally spotless sky. Some of the hills were scarred by wind-carved blowouts, sandpits that looked white in the distance. Barbed-wire fences trailed over the slopes, and here and there at the base of a hill stood a tree or two. In the wide valleys the glittering blades of windmills spun at the top of tall steel frames, pumping clear, cold water into low, circular tanks. Black cattle drifted along below the hills, grazing or going to the wells. A calf might bawl for its mother, or a bull might bellow to a rival. A skein of pronghorn, white rumps blazing in the sun, might stream across a flat; a mule deer might stand atop a high hill overlooking denim-clad men working in a hay meadow. Hawks often wheeled in the sky, and almost always the melody of western meadowlarks played over the pastures. The terrain itself was more or less unchanged by the inroads of the livestock industry. Native prairie grasses, at least knee high, rippled in the wind, rolling like the surface of the sea; shallow ponds of clear, chill water nurtured families of ducks.

Before I left my suburban Omaha home to go to the Sandhills, on the first day of summer, I wanted to read about what I might expect of ranch life. So I picked up a collection of the writings of Theodore Roosevelt and read his descriptions of ranching in the Badlands of 1880s Dakota Territory. Certainly, ranching had changed in the ensuing decades. Texas longhorns, common commercial livestock in Roosevelts era, were curiosities kept for ornamentation in my time. Virtually all cattle and horses in the Sandhills were registered animals with long bloodlines. We almost always rode to and from pastures in a pickup truck, and we used a two-way radio for communicating with the house and with neighboring ranchers.

But in critical ways, life in cow country had not changed. Ranching still demanded men and women who did not complain of hardship (the rancher with whom I worked had broken almost every rib in his body over the course of his first forty-five years, having been jumped on by a horse, for example), and the work was still subject to the whims of natureblizzards and such. Some days, exactly as had Theodore Roosevelt and his crew, we saddled roughly broken horses, which might buck when mounted, and trotted out to distant pastures to move cattle. We rode to the sound of creaking leather, jingling spurs, and clopping hooves muffled by sand; sunlight melted into sweat on the horses shoulders, and the fragrance of wild grasses sweetened the air. We would round up cows and brand their calves with glowing irons, amidst the odor of singed hair and burning flesh, in the way that disturbed one of Theodore Roosevelts ranch hands. We kept rifles in a rack over the pickups rear window and shot occasionally at some poor random beast that was not protected by lawa coyote, perhaps, or a prairie dog. To paraphrase Roosevelts comment on the open range, we felt the charm of ranch life, exulted in its abounding vigor and its bold, restless freedom, and felt real sorrow for those who would never know what is perhaps the pleasantest, healthiest, and most exciting form of American existence.

Next page