Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

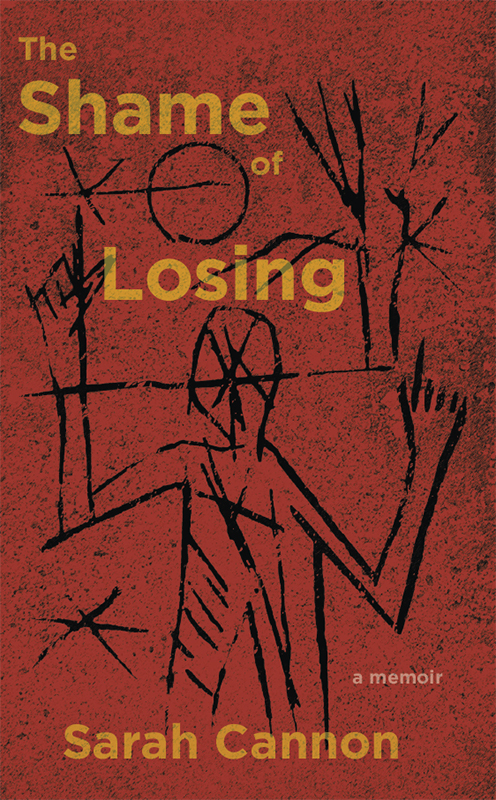

THE SHAME OF LOSING

THE SHAME

OF LOSING

A MEMOIR

Sarah Cannon

The Shame of Losing

Copyright 2018 by Sarah Cannon

All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of both the publisher and the copyright owner.

Book layout by Amber Lucido

ISBN: 978-1-59709-624-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018031084

The National Endowment for the Arts, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, the Ahmanson Foundation, the Dwight Stuart Youth Fund, the Max Factor Family Foundation, the Pasadena Tournament of Roses Foundation, the Pasadena Arts & Culture Commission and the City of Pasadena Cultural Affairs Division, the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, the Audrey & Sydney Irmas Charitable Foundation, the Kinder Morgan Foundation, the Meta & George Rosenberg Foundation, the Allergan Foundation, the Riordan Foundation, and the Amazon Literary Partnership partially support Red Hen Press.

First Edition

Published by Red Hen Press

www.redhen.org

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to dedicate this book to my late Nana whose love for books and family will always be with me. The second dedication is for my Mom & Dad, who have been there for all of it. I love you. Thank you to everyone at Red Hen Press, especially Monica Fernandez, Keaton Maddox, Rebeccah Sanhueza, and Kate Gale. To my mentors in the Creative Writing program at Goddard CollegeAimee Liu, Darrah Cloud, and Ryan Boudinotthank you. Heartfelt appreciation for Jessamyn Smyth for the time at Quest Writers Conference in Squamish, B.C., and for Rebecca Brown, my mentor there. The constant encouragement provided by writers and readers Samantha Kolber Pyatak, Ginna Richardson Luck, Julie Shayne, Heather Ohly, and Francine Walsh has made my finishing this book possible. And for proof that friendship can lift you up, thank you to my closest onesyou know who you are. For their profound support, I wish to thank Ned and Maura Cannon. Last and most importantly, I want to express my deep-felt respect for Miles, whose strength in survival we might all look toward when life throws us sideways, my least favorite word. Memory is fickle and contestable. This version is only mine.

Thank you to the editors who published essays of which parts or themes of which appear in this book: Dan Jones at the New York Times; Sarah Hepola at Salon.com; Abby Murray at Collateral Journal.

Credits: Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor, Lee Woodruff & Bob Woodruff, Erich Maria Remarque, Frank Ocean, Norah Jones, UW Harborview Medical Center, Kevin Pierce & Crash Reel, Brain Injury Alliance of Washington, Mark OBrien & The Sun Magazine, Thich Nhat Hanh, and Yue Minjun.

For Eliza and Will and childhood survivors everywhere.

PART I

O n October 30, 2007, I was volunteering at a local arts center in our suburb, preparing for an auction. Halloween was the next day and I was thinking about our five-year-old daughter Lizzies oversized, pink cowgirl costume. Isaac, just two and a half, was going as Superman. My husband Matt, a crew lead for an arboriculture company, would meet us after work at my parents house in Magnolia, a neighborhood in Seattle. He and his team were planning to remove a bigleaf maple in Issaquah. I came back to my desk and assumed the three missed calls meant Matt was trying to reach me regarding domestic logistics. Should he pick up a flank steak? Did we need milk? I didnt bother listening to the messages and called him right back. But Matts co-worker, young Teddy, answered.

Oh God, he was saying, over and over.

I could hear moaning in the background and a siren.

Stay still, Matt, Teddy was saying. My mouth, so dry, formed words that sounded oddly natural.

What happened?

Jesus, Teddy said. His cheekbones are sideways.

I created an image of Matts brain drowning in blood, his face smashed to pieces. Teddy was talking to the EMTs who said for me to meet them at the hospital. Harborview, Teddy told me, the hospital downtown. Dont let him die, I begged silently. I ran to my car, my throat sensationally dry, like there was a small kitchen cloth towel shoved down deep inside. I wanted to gag. Val, my boss, saw me grab my coat and purse in a panic and followed after me as I ran.

Is it the kids? she shouted. I shook my head no: it was my husband. There had been an accident. It was serious.

Val helped me fish my keys from my purse. The landscape was like a blurry mirage and she shook my arms and said, Do you know how to get to Harborview? I nodded yes and asked, screamed, for everyone to please pray. I sounded foreign to myself, panicked and lost. Driving to the emergency room, my lips went from cold, to cold and itchy, to cold and itchy and rubbery. My hands trembled but there was this keenness in my mind, as if something outside my body was dialing in a necessary focus, and I heard these words on replay, like a roll of tape, a succession of thoughts: OK, hes badly hurt. But Teddy said he was moving. If hes hurt, please dont let it be so bad he cant recover.

I pulled into the hospitals roundabout entrance and let my SUV idle. I hopped out and dangled the car keys at two calm uniformed men. One helped me with my car and the other escorted me to the social worker area. The intake lady sat me in one of the baby blue plastic scooped seats. The whole place smelled like urine. Street people made up the bulk of people waiting. The intake lady clicked her acrylic nails over her keyboard and used a yellow walkie-talkie. I heard fuzzy static in my inner ear.

This was Harborview, where a friend had her stomach pumped in seventh grade; where my friends brother got treated after an assault with a baseball bat at a house party; where a family friends child was flown from Whistler after he snapped his vertebrae skiing. It is a Level I trauma center, the highest level of care for all serious injuries and burns, serving patients from Washington, Montana, Alaska, and Idaho. It is the place, someone would tell me later, where half the arrivals end up in the county morgue.

I had taken great care with my outfit that morning. I wore a black, floor-length wrap skirt, knee-length wool socks, engineer boots, and a thin cashmere hoodie. I sat there freezing. The social worker had cold hands with large veins. She led me into a private waiting area and gave me a warm blanket to stop my uncontrollable shivering. I would need to wait here for a few more minutes; hed only just arrived, and that was all the information she had. I couldnt talk, so I nodded. I signed some papers and nodded when she asked if I had family to contact. Does Matt have parents? I said yes, his mother lives in Salem. She wanted me to call her and I shook my head: no.

The thing is, she said, if he passes on she will want to know when it happened, and trust me, you dont want to have to tell her you waited on news of the accident.

I was in the epicenter of horror and I understood. I would do it, I assured her. Then she left me. Sitting there alone I felt abandoned by the world. What God would do this? What kind of life would we be living? I doubled over, making myself as small as I could, hugging my own body like I used to as a small child. She returned and walked me through swinging doors and long bright corridors to see him. Matt was the only patient behind the green vinyl curtain. His sweatshirt was cut open and electrodes were stickered to his perfect chest. Nurses tended to him and I hardly wept because he looked so beautiful. His work-wear jeans were soiled with chainsaw gas, and wood chips laced the inside ankle cuffs. The nurses stared at me as I stared at him.