June 1980 Life in the Garden of Eden

RAPID-FIRE GUNSHOTS WOKE ME early in the morning. The sound always felt like a new experience, shredding my heart into ribbons. I jumped out of bed, gasping. I ran outside in my bare feet, racing for my life. Ta, ta, ta and then silence. I tried to pluck the terrible thoughts out of my mind, but my heart knew that somewhere, not far away, life had ceased and everything had turned upside down. Thats how it had been since the revolution.

I joined my two brothers, who were trying to distract themselves with a game on the veranda. Our dog, Metew, was spread out on the grass, nervously wagging her tail. We never spoke of the gunshots. We had silently figured out what they meant a long time ago, and we were forbidden to talk about it. So the three of us sat on the steps of our house, pretending nothing had happened, inhaling deep lungfuls of the Addis Ababa morning air that was filled with the aroma of the tall eucalyptus trees dominating our landscape. Soft white light filtered through the trees. The birds were chirping, neighbourhood dogs barked excitedly as the morning sun covered us like a warm blanket.

As long as I was with my brothers, everything was all right.

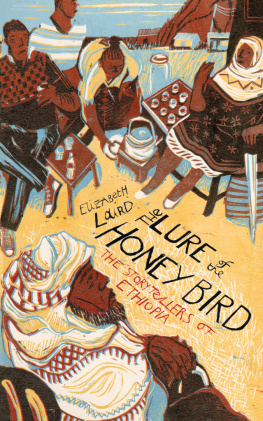

Lets play gebeta. Yared offered.

Last night, I was having this strange dream, Asrat said, collecting four pebbles from one of the eight gebeta holes and dropping one stone in each of the holes that followed. I was walking and running a long distance, through strange places I had never seen before, when I arrived at a raging river. I stood trying to figure out how to cross it. I saw the flat head of a hippopotamus jutting out of the water.

Asrat studied the gebeta holes for his next move, but Yared was already beaming with a winners smile.

Asrat gathered the five pebbles from where he had dropped the last stone and told us the rest of his dream. I had to cross the river, so I entered the water and the head of the hippo turned into a rock. I jumped onto the rock. I could see the rough river twisting like a cobra beneath me, carrying dead animals, logs, and garbage. Sweating and feeling sick, I searched for another rock to jump to, but the water rose up, and the rock I stood on was now covered with water. I regretted entering the river in the first place. Finally, I spotted another rock next to me and jumped on it and then there were about eight or nine flat rocks on which I stepped to reach the other side of the river. I sensed I had to move quickly. I jumped on each rock as quickly as I could. The river slapped my legs, throwing me off balance, but I kept running until I crossed it. I sprang off safely and landed in a puddle of mud.

You should tell Tetye, I said. (We always called our mother Tetye, which meant sweet sister, because we grew up hearing her four sisters calling her that.) Tetye always told us to pay attention to our dreams. She believed that dreams predicted the future and revealed aspects of our lives that we failed to see.

It felt so real! When I jolted out of bed, I was drenched in sweat. Ishi, ishi! Okay, I will tell Tetye.

I can interpret your dream for you, Yared said, the wide smile on his face growing wider. He gathered up the pebbles from one of the holes, and took his turn. It means you are going to lose this game very badly, ha, ha, ha!

Yared was the champion at every game we playedcards, checkers, ping pong, and marbles. He was eighteen, Asrat was sixteen, and I was fourteen.

I liked comparing my brothers twinlike appearances. Their hair, shaved around the ears leaving only a curly crown of hair on top; now both were the same height and at times it was difficult to tell them apart. They were taller than most of their classmates, and while Asrat maintained a clean-cut look, Yared had an Afro. When I stood between them for family pictures, because of the height difference we formed the letter M. One thing we all had in common was our slenderness. We were thin in a time and place where people preferred a chubby look in children and adults alike.

We could hear our baby sister, Kalkidan, crying inside, and my stepmother, Meskerem, soothing her. I used to be the youngest until nine months ago when Meskerem gave birth to Kalkidan. Meskerem, in her early twenties, had long thick black hair that was always oiled and kept in large curls on top of her head. It looked like a basket. When she met my father, she was the administrative assistant in his department at the Ministry of Agriculture.

The veranda was our favourite place. It was long and narrow, like a hallway, with a shiny hardwood floor. A few steps down from us the rose garden was in full bloom. Moist green grass covered the area up to the fence, and beyond that the rows of eucalyptus trees spread throughout the neighbourhood.

Come on, Beth, its your turn, Yared said. I got ready to play. A strong sun was now on my back.

I was distracted by the sound of a car horn.

Is it Terrefe? my stepmother Meskerem asked. Terrefe was my father. She rushed out to the veranda carrying Kalkidan.

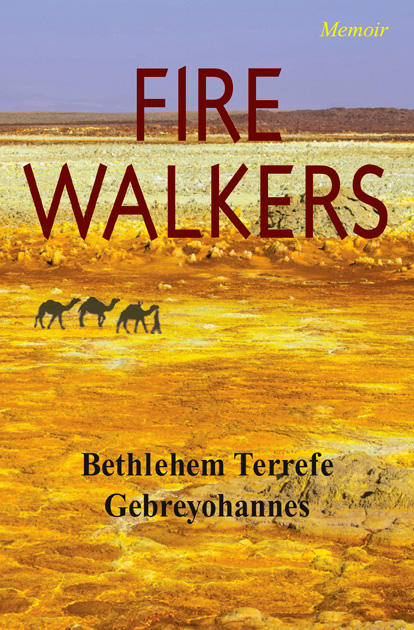

The guard opened the gate and my fathers green Land Rover pulled into the driveway. We hadnt seen Abba for two months. My brothers and I ran up to him, shouting Papa, Papa! Metew wagged her tail and leaped around as Abba stretched out his arms wide and we fell into his embrace. I knew he hated being away from us because he often took us with him. The new military government, the Derg, had dispatched him to the Afar district of Assayita, in the province of Wollo, to manage a settlement program. Assayita, he told us, was sweltering hot, without proper medical facilities or schools.

Abbas presence was like Christmas, Easter, and birthdays all combined. He had come laden with aromatic gifts from the distant province. Mine was a leather handbag, buttery smooth and fragrant. For Yared and Asrat, there was soft wool fabric to be made into suits. And for all of us, brand new Adidas shoes. Mine were blue and white.

A young man emerged from the back of the car, followed by a large, beige-coloured ram. I recognized him as the local butcher. He was wearing tattered brown shorts with patches on the back and black rubber sandals made from a car tire. He led the ram to the back of the yard to be slaughtered. I followed Yared and Asrat to the car to help unload. As we took the things into the house, I could hear the rams bleat. It would not last long, the butcher would drop the animal to the ground, tie its four legs together, and then offer a prayer,