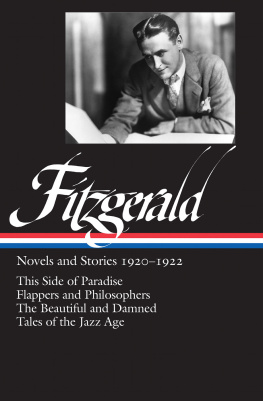

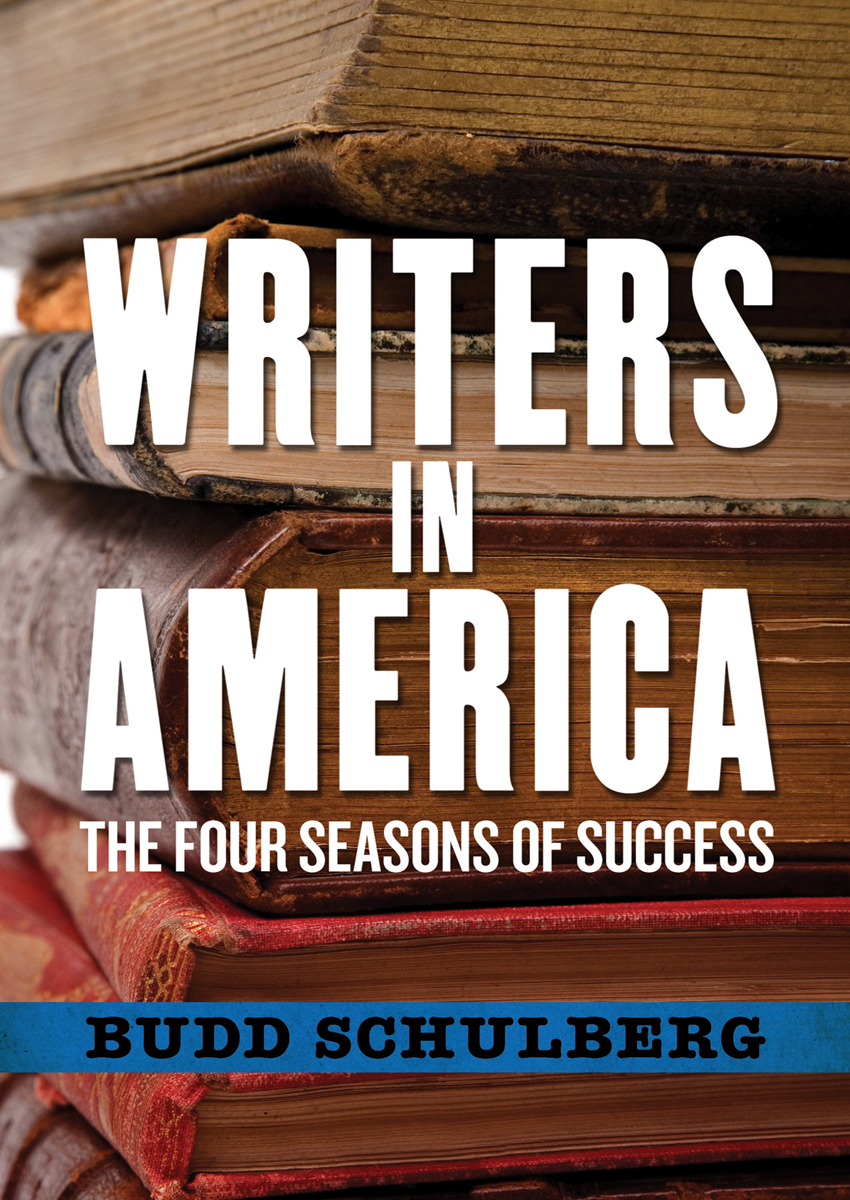

Writers in America

The Four Seasons of Success

Budd Schulberg

TO THE MEMORY OF SAXE COMMINS

an editor for all seasons

who nursed three Nobel Prize winners

and a brace of Pulitzer Prizers

through bountiful summers and bitter winters

When Herman Melville died in 1891, the literary journal of the day, The Critic, did not even know who he was.

The older generation remembered that Herman Melville had once been famous. He had adventured in the South Seas on a whaler; he had lived among the cannibals; and in Typee and Omoo he had made a romantic pastiche of his experiences. On these books Mr. Melvilles fame had been founded: it was a pity he had not done more in this line; for his later books, obscure books, crowded books that could be called neither fiction nor poetry nor philosophy nor downright useful information, forfeited the interest of a public that liked to take its pleasures methodically.Both the fame and the later absence of recognition, Mr. Melvilles commentators agreed, were deserved. By his interest inmetaphysics, Mr. Melville carried his readers into a realm much too remote, and an air too rarefied; a flirtation with South Sea maiden, warm, brown, palpable, was one thing: but the shark that glides white through the sulphurous sea was quite another. In Moby-Dick, so criticism went, Melville had become obscure: and this literary failure condemned him to personal obscurity

FROM LEWIS MUMFORDS PREFACE TO Herman Melville (1929)

Introduction

IN PRECEDING CENTURIES AND carrying over into our breakaway twentieth, it was par for the literary course for writers to know each other. There were circles like the Lambs, to which the established authors of their day, Carlyle, Coleridge, De Quincy, and other peers would naturally gravitate to gossip, complain, and exchange ideas with Charles and Mary on their Friday Afternoons. If novelists were not personal friends involved with each other like Melville and Hawthorne, they were at least professional acquaintances like James and Wells. Diametrically opposed in style and outlook, the latter pair considered it one of their literary duties to express their differences in an urbanely combative correspondence.

Before the First World War it was still common for literary folks to fraternize. There was Mabel Dodges salon for movers and shakers in Greenwich Village, where John Reed, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Big Bill Hey wood, and other artists and actionaries passing through would assemble for poetry reading, wine drinking, lovemaking, and revolutionary dreaming. There was the Chicago School of Carl Sandburg, Edgar Lee Masters, Sherwood Anderson, along with a marqueeful of only slightly lesser lightsBen Hecht, Charles MacArthur, Louis Weitzenkorndrinking, praising, and damning together. Even in the Jazz Age it was still literary etiquette for a young man of promise to send politely inscribed copies of his new book to Edith Wharton, T. S. Eliot, or other established literary figures of his day. There was every sort of exchange, from Scott Fitzgeralds genteel tea-time encouragement from Edith Wharton and Eliot, to his Long Island drinking bouts with Ring Lardner. There were stormy confrontations: Hemingway vs. Max Eastman, chest to chest in their editors office; Hemingway vs. Morley Callaghan with an embattled Fitzgerald holding a controversial stopwatch on their boxing match in a Paris gymnasium; Fitzgerald vs. Thomas Wolfe in an exchange of literary positions more acrimonious than Wells and James.

When most of our good young writers of the twenties stayed on in Paris after the war or migrated there to escape what professional grump H. L. Mencken called the American booboisie, they found literary camaraderie and enemy groupings at Gertie Steins and at the clubby bookshop of Sylvia Beach: not only Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Lewis dedicated themselves to congenial expatriatism, but also Kay Boyle, Robert McAlmon, Ramon Guthrie, Archibald MacLeish, Henry Miller, Carl Van Vechten, and the mad rich poet Harry Crosby, who lived in a celebrated windmill with his fabulous Caresse.

Back home in those days when Life was a humor magazine and the President of the United States was someone to chuckle over rather than demonstrate against, the Hotel Algonquin regulars included wits who could float like butterflies and sting like bees: Dorothy Parker, Heywood Broun, George S. Kaufman, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, and others just as mean and merry. Eventually that caustic Camelot fell apart as a score of the best writers in New York went West to make a lot of money writing dialogue for the talkies. One day I stood in the Garden of Allah in Hollywood, by Alla Nazimovas enormous swimming pool that was said to have been built according to the sirens whim in the shape of the Black Sea, on which she had lived in her Crimean childhood. The exotic pool was surrounded by pseudo-exotic stucco villas shaded by banana trees, loquats, and other tropical growth. I had just stepped out of the bungalow rented year after year by Edwin Justus Mayer, once a distinguished New York playwright (Children of Darkness, The Firebrand), with whom I was collaborating on an undistinguished Bob Hope comedy for Sam Goldwyn. I heard the unmistakable laughter of Bob Benchley, one of the nations pre-eminent humorists, then the property of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. I remember looking around in wonder at those bogus villas where some of Americas better writers clustered together for warmth: in those back-lot Spanish beds slumbered or tossed Donald Ogden Stewart, S. J. Perelman, John OHara, Corey Ford, Scott Fitzgeraldsome of them, like Scott, Benchley, and Eddie Mayer, seemingly trapped in the Garden of Allah like flies to honey paper, others merely passing through, like Marc Connelly, Woollcott, and Lillian Hellman. But what a gathering of literati it was, at Benchleys never-closing bar, with Dorothy Parker, Samuel Hoffenstein, Somerset Maugham, and a rare assortment of the more literate drinking actors, Bogart and Barrymore, Errol Flynn, Charlie Butterworth, and the Laughtons. It was almost as if the Algonquin Round Table had been moved cross country into the Garden and under the palm trees. Only the banter was underlined with more bitterness here as so many of the writers knew they were debasing themselves and did their clever best to laugh off their shame in pointed jokes about their studio bosses.

Those days of literary affinity have long since been fractured and fragmented. Even the boys in the back room of the good old Stanley Rose Book Store on Hollywood Boulevard, where we used to drink orange wine and talk Life and Literature with Bill Saroyan, Pep (Nathanael) West, John Fante, Horace McCoy, Aben Kandel, Jo Pagano, and other young hopefuls, no longer have a back room to go back to, or the energy or wish to establish another.

No, those were groupier days. And the spirit of now seems to be summed up in the porcupine manifesto of a standoffish writer I pass occasionally in the night: I dont want to meet other writers. The last literary group to hang together were probably those wandering beatifies, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, John Clellon Holmes, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and the other beloved infidels who expressed their contempt for the straight life of the Eisenhower days by taking to the road and becoming generation outlaws with a passion and a vengeance.