T HIS IS A work of nonfiction, as true an estimation of events as I am able to tell. A few names have been changed to avoid confusion and protect minors; some people are identified by only a first name, last name, or nickname. I personally witnessed many of the events described in these pages. Many scenes were also narrated from descriptions given by participants, as well as from photos, videos, and other documentary evidence. Thoughts attributed to people in this book were all described to me firsthand in interviews. Quotes from conversations that took place when I was not present were recounted by subjects and checked wherever possible with the other participants.

O N A COLD AFTERNOON, before the end, they sauntered together out to the smoke shack behind the factory in Indianapolis and spent their fifteen-minute break asking one another What would you be, if you could be anything, and money didnt matter at all?

Inside the Rexnord factory, the machines that were still left on the factory floor beeped and whirred, as if calling out to the machines that had already been taken away. The workers lit their cigarettes and wondered what would become of the people whose names had already made the layoff list.

For those workers, the factory had been a world unto itself. Family dynasties had risen and fallen on the factory floor. In its break rooms, rivals had gone to war and made peace. Under those rows of fluorescent lights, forbidden love had flourished and faded. The factory had a hierarchy and its own etiquette and its own lexicon. Years after it closed, a funny thought would strike someone whod worked there that could be understood only by someone else whod worked there, too. It had been a cloistered place, shut off from the world. Inside its walls, each worker had an identity, a role.

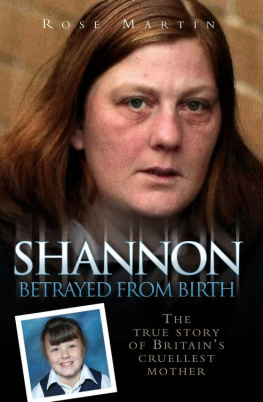

Some worked on the loading dock, carrying steel pipes off the trucks and into the plant. Others worked in the turning department, slicing the pipes into steel rings as small as a bracelet or as big as a coffee table. Still others piled the rings into barrels and wheeled them over to the heat-treat department, where a white woman named Shannon Mulcahy, who loved heavy metal music and abandoned dogs, packed them into wire baskets and sent them into furnaces, hardening them with fire. Then Shannon sent the hardened rings across the aisle to the grinding department, where her cousin Lorry honed and polished them. Then Lorry sent them to the open space in the plant where assemblersthe most prolific among them a black man named Wally Hall, who was known for his mouthwatering brisketput them together inside cast-iron housings. The housings came from department 103, where a white man named John Feltner, who had just recovered from a bankruptcy, carved rough-hewn iron hunks to a specific size and drilled the right number of holes.

The finished product? A steel bearing.

Bearings are gadgets designed to reduce friction. The concept has existed since ancient times, when people transported heavy stone blocks by pushing them atop rolling logs instead of dragging them across the ground. Those logs could be considered the earliest roller bearings.

During the Roman Empire, royal boats were equipped with rotating tables to display religious statues. Craftsmen made them by taking circles of wood, digging out little holes around the circumference, and inserting metal balls inside that could spin. A second circle of wood rotated atop the balls, which could be considered the worlds first ball bearings.

Inventors kept adding to the concept. Leonardo da Vinci designed a new kind of bearing around 1500. Galileo invented another one a century later. In 1794, a Welsh ironmaster received the first ball bearing patent in the world, for a carriage axle that used spinning metal balls.

Today, countless varieties of bearings exist. Many of the bearings that the Rexnord factory made had an inner ring that could be tightened around a shaft and an outer ring that was free to spin like a wheel. Bearings are essential for nearly every machine that moves: Bicycles. Cars. Tanks. Conveyer belts. Wheat combines. Fighter jets. Escalators. Fans.

The state-of-the-art 410,000-square-foot factory opened on the West Side of Indianapolis in 1959, to gushing praise in the Chicago Tribune. Link-Belt, the company that built it, made the Cadillac of bearings, so high quality that orders poured in from far-flung corners of the globe: Sugarcane harvesters in Cuba. Iron ore mines in South America. Oil wells in California. In Indiana, Link-Belts name adorned a water tower and a fleet of trucks. Working there conveyed a certain status. You are a member of a great industrial family, declared an employee handbook from 1955. The products you help make bear Link-Belts Symbol of Quality known throughout the world.

More than half a century later, the building had aged. Its roof leaked brown water onto the machines when it rained. About three hundred people worked on its factory floor, half the number it had been designed to hold. The plant had been bought and sold more times than anyone could count. The workers had been passed from owner to owner, just like the machines they ran. Rexnord, a Milwaukee-based industrial supplier, owned it now. But the workers still took pride in the Link-Belt name, which lived on as a brand, written in proud letters on the cast-iron housings of the most expensive bearings they made.