Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

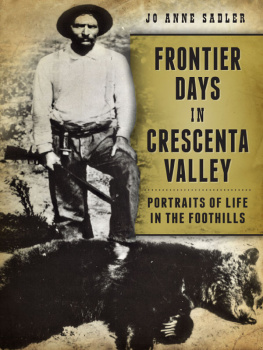

Copyright 2014 by Jo Anne Sadler

All rights reserved

Cover image courtesy of John W. Robinson.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62585.042.3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sadler, Jo Anne.

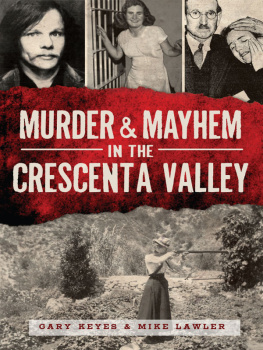

Frontier days in Crescenta Valley : portraits of life in the foothills / Jo Anne Sadler.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-508-0

1. Crescenta Valley (Calif.)--History--19th century. 2. Frontier and pioneer life--California--Crescenta Valley. I. Title.

F868.L8S166 2014

979.4'93--dc23

2014014068

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

No man is an island, and neither is an author, especially when writing historical books. Again I thank Melissa Patton, director, and Tim Gregory, archivist, at the Lanterman Historical Museum Foundations. Thanks to the Glendale, La Crescenta, Montrose, La Caada Flintridge and Pasadena Public Libraries; the Southern California Genealogical Library; the Huntington Library Archives; and the Pasadena Museum of History.

Individuals who have generously shared their photographs are Jacqueline Kennedy, Lori Ward Kent, Timothy MacDonald of Beinn Bhreagh Vineyard and John W. Robinson. Thanks to William Lewis of Bills Bees for graciously giving me a tour of his apiary in Angeles National Forest.

Using primary sources, newspapers and writings of the day gives a voice to the events as they happened, rather than basing the narrative on thirdhand information.

The Historical Society of the Crescenta Valley and its supporters in the past twelve years have generated and inspired many new books about Valley history, and they are to be commended for being such a force in local history.

Unless otherwise noted, photographs and graphics in this book are from the archives of the Historical Society of the Crescenta Valley and the La Caada Congregational Church photography collection at the Lanterman Historical Museum Archives.

INTRODUCTION

This book is a companion to Crescenta Valley Pioneers and Their Legacies, which featured the early nineteenth-century settlers who left a permanent imprint on the Crescenta Valley. Frontier Days continues the journey and chronicles the challenges of daily life, beekeeping, hunting, major incidents and lost landmarks.

While the Crescenta Valley was not the Wild West, it was a frontier area, a place living on the edge of civilizationin this case, the nearby city of Los Angeles. It was remote, and people looked to one another for support and their social life. Until the Arroyo Seco Bridge was opened in May 1893, even getting to Pasadena necessitated crossing the rugged Arroyo Seco, which could be very dangerous in rainy weather.

In our modern lives, we tend to view the olden days through rose-colored glasses, longing for a simpler, less complicated life. While it was a simpler time, it was a much harder lifeno welfare net, corner takeout, electricity, refrigeration, telephones, washing machines or 911 assistance. Meat and chicken did not come from the supermarket wrapped in plastic but as a result of hunting and butchering it yourself. Children were born at home, and many died from common childhood illnesses; an appendix attack often resulted in death due to the distance from medical care, and there were no antibiotics, much less penicillin. There was no TV, movies or Internet accesswhile offering us more diversions, they nonetheless make for a more independent, isolated life today.

Using newspapers and writings of the day, I have attempted to give a realistic view of how people thought and lived. They may have not have been as politically correct as we would like in our modern day, but we cannot look at nineteenth-century people from twenty-first-century viewpoints. We must try to put ourselves in their time and place.

CHAPTER 1

BEE RANCHING AND GREASEWOOD

Making a Living in the Early Days

When the first pioneers settled in the Valley, the land was in a natural state, totally undeveloped and full of native plants, sage, deer, rabbit, quail, bears and lots of rattlesnakes. Much has been written about all the fruit, vineyards and olive groves, but before pioneers could even begin planting, the land needed to be cleared of greasewood and other native plants and a reliable water source secured. Then, after planting their orchards, there was a three- to five-year wait until the groves and grapevines would start to be commercially profitable.

When Henry Hancock surveyed the boundaries of Rancho La Caada in 1858, he did not venture into the mountains but rather marked them unsurveyablegood for bees only.

The September 1875 government survey that established the township lines for Township 2N included this general description: There is a very small proportion of agricultural land in this Township situated along the Northern boundary of the Rancho La Canada. There are settlers along the foot hills who are principally engaged in Bee Culture. The Mountains are high with scattering Timber: Oak, Pine and Fir, the greater portion of which is only Valuable for Fuel.

What did the settlers do to support themselves while waiting for the orchards to start to produce? I am not talking about moneyed men like Adolphus Wesley Williams, Dr. Benjamin B. Briggs and Dr. Jacob Lanterman, each of whom came here with the means to purchase large tracts of land with the intent to subdivide and make a profit, or men like Thomas Spencer Hall who lived and worked in Los Angeles and developed properties in their spare time. I am talking about the very first rude forefathers of the hamlet, as Charles Pate called them. These settlers had no plan to fall back on, but they did have families to feed and needed to make a living from day one.

Farming is a seasonal business, always at the mercy of nature; farmers traditionally have had more than one way to earn a living. The early settlers planted quick grain cropsbarley for animal fodder, alfalfa for the dairy cows, hay, pumpkins and melons between the newly planted orchardsand hired out with their wagon and team of horses for five dollars per day. They would sell their animal and rattlesnake skins to hide dealers in Los Angeles. The women, like farmwomen everywhere, sold or bartered their excess eggs and milk, would take in laundry and mending, took in boarders and worked in the seasonal harvests and local packing operations.

There was timber harvesting early on, but that involved a more expensive operation of hauling and transporting timber down the mountains to the city of Los Angeles and was financed by moneyed men from Los Angeles. In the early days, for the earliest settlers, there was only greasewood and bee ranching.

GREASEWOOD

One source of income was selling cleared greasewood plants for a few dollars per wagonload for fuel in Los Angeles. In 1885, the Wood-Growers Yard on Los Angeles Street was selling greasewood for seven dollars per cord delivered. Greasewood is a highly flammable native plant that is found in the Southwest and West and is a good source of fuel. The type of greasewood found in Southern California is different than the type in the Southwest and is sometimes incorrectly called sagebrush.

Next page