To the Rangers and Marines who gave it all.

RLTW and Semper Fi.

CONTENTS

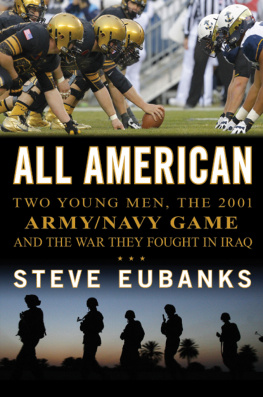

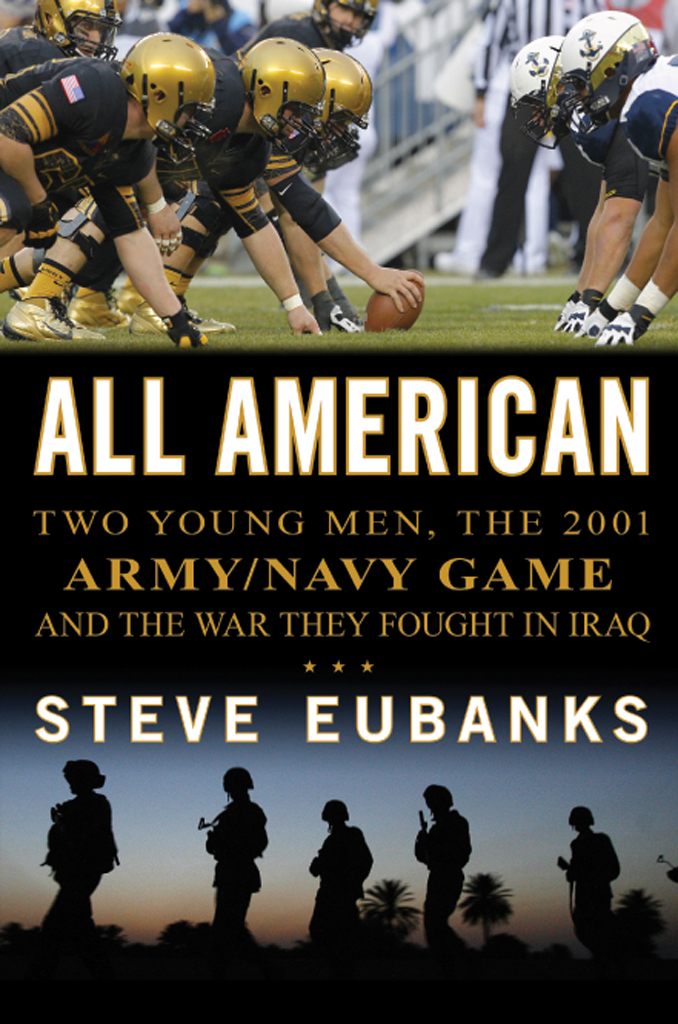

First and ten at the Army thirty-six-yard line.

Both teams trotted from the south end of the field to the north as whistles announced the end of the first quarter. Had it been the start of the fourth quarter instead of the second, all the players would have sprinted from one end to the other, a tradition meant to display the indefatigable spirit of football men. None of them knew how the tradition started, and now that every high school and college team in the country was doing it, toosome while holding four fingers in the airit seemed to have lost its luster.

No fingers were lifted for the second quarter, a break in the action that warranted only a light jog as a fresh fifteen minutes flashed on the game clock and sixty-seven thousand fans stood and stretched their legs.

From the field, the movement of the crowd looked like water cascading down the walls of a well. Some of the fans still waved tiny American flags, the ubiquitous pompoms for this contest, while others shed their jackets and sweaters, exposing arms and necks and the occasional coed shoulder. By 1 P.M . the temperature had crept above seventy degrees in Philadelphia, sunbathing weather for the first day of December 2001.

The fans had been in these rigid old stands for hours before kickoff, many arriving at sunrise to watch the cadets of West Point and midshipmen of the United States Naval Academy fall into formation in the parking lot, a spectacle so foreign to most college football fans that they were left shaking their heads in wonder. No one cared that Veterans Stadium sagged under the weight of indifference and looked much older than its thirty years. Built in the late sixties to keep the Phillies from moving to Cherry Hill, New Jersey, and to provide a home to the Philadelphia Eagles, who once played their home games at Franklin Field at the University of Pennsylvania, the Vet had been inadequate from the moment the doors opened in 1971. Even though dual-purpose stadiums were all the rage at the time, with Atlanta, Washington, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh opening squatty, circular coliseums, the dimensions and requirements of the baseball diamond and football field were so different that most of them worked well for neither. Early-season football games were played on dirt infields, and fifty-yard-line seats were often as far away from the action as you could get.

Veterans Stadium had all those problems and more. The place was overrun with mice, and many of the creaky seatssoon to be meticulously removed and sold as souvenirsstuck open or shut. The paint was cracked, and the elevators rumbled and wobbled in ways that made fans want to take the ramps.

On this day no one cared. Veterans Stadiumhard, gritty, and named for veterans of all warsseemed like the perfect spot for the Army-Navy Game, even though neither academy had anything to do with it being held there. Philadelphia is close to equidistant between West Point, New York, and Annapolis, Maryland, so with few exceptions the game had been played in the City of Brotherly Love since 1932, mostly in the old Municipal Stadium. As for the name, Philadelphia city councilmen voted to call it Veterans Stadium in 1968 as both a tribute to those who served their country and a less-than-subtle snub at the Vietnam protesters whose numbers were swelling at that time.

There were no protesters on this day. That would come later. Today, emotions ran high. Many of the spectators had already cried themselves spent. Some hugged, while others made mental notes of every tidbit of history they witnessed. This football game between two losing teams, a meeting that would have no effect on the college football standings, had become a rallying point for the country, a healing salve on a gaping national wound. Fires from the World Trade Center still burned eighty-one days after September 11.

And this was now the most watched college football game in the country. Four million American television sets tuned in early that Saturday afternoon, with another four million sets tuned in overseas.

Army led Navy, 130.

The Cadets of the United States Military Academy at West Point had scored on their first two possessions and would have been up 140 if not for a missed extra point by kicker Derek Jacobs. That miss gave hope to the U.S. Naval Academy Midshipmen. Armys quarterback, Chad Jenkins, was playing on an injured knee, a condition far more serious than anyone realized at the time, and one that affected his passing accuracy. A brace that looked like something out of the Spanish Inquisition gave him the ability to run on torn ligaments, but if he twisted the wrong way during a throwing motion, the ball could go anywhere and he could end up writhing on the ground.

Armys last possession of the first quarter had ended with Chad throwing an ugly interception, the sort of wobbly jump ball that was every quarterbacks nightmare. Navy wasnt able to capitalize, but the momentum had shifted to the Mids.

They needed to hold Army on this drive. The difference between two scores and three is far greater than numbers on a board. Comebacks are built on the belief that the mountain is not too high, the time is not too shortthe obstacles are not too great. Thirteen points down with three quarters to play was not that big a hole, and both teams knew it.

The players were thrilled to focus solely on football, at least for this day. The cheers, grunts, yelling coaches, and smells, the thick grass wedged in their fingers and soft soil under their cleats were all a welcome reprieve from the knowledge that they would soon be called to do hard things. Even though American football at the turn of the twenty-first century was applauded for its militarism and the way it prepared young men for life in another kind of uniform, the chaos, nuance, strategy, beauty, and violence of this game, with its tradition of rivalry between two branches of the nations military, allowed these players to push aside all thoughts of war. For three and a half hours, they could focus on a sport they had played since they were children. The gridiron had become the one place in their lives where nothing seemed off-kilter.

Fifty of the players were seniorstwenty-six from Army and twenty-four from Navyand that meant they were just a few months away from the reality of commanding men in combat. For some of them, the main reason for enrolling in the academies was to get an education on par with those of the best Ivy League schools, plus a guaranteed job out of college. Others were legacies (offspring of career military fathers or mothers). They never expected to see actual conflict. Then there were the men and women who had longed to be soldiers, sailors, or marines since they were old enough to pick up a toy gun. More than a few fell into a category the Army referred to informally as hooah, a gung-ho catchphrase that meant everything from Do you understand? to Lets take that hill!

Hooah is the guy obsessed with polishing every buckle and shoe, who wants to be Infantry, Airborne, and Ranger, and who cant imagine a life not spent in uniform. If he wasnt at West Point, the hooah guy would be in the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) or working his way through the enlisted ranks and applying to Officer Candidate School (OCS). Navy had them as well, although their pronunciations were different. Those heading into the SEALs are hooyah!, and marines, oooRAH!, shouted from the back of the throat like the gravelly bark of a bloodhound.

But for all of them, the answer to why they were there eventually came around to the quarter-million-dollar answer: its free. The grand bargain at the United States Military Academy and United States Naval Academy (and the Air Force Academy as well) is that in exchange for a five-year military commitment, cadets and midshipmen need only show up on campus with underwear and a toothbrush. Everything elseclothes, shoes, food, room, furniture, books, backpacks, and tuitionis paid for and provided by the government of the United States, a value estimated at between $250,000 and $300,000.