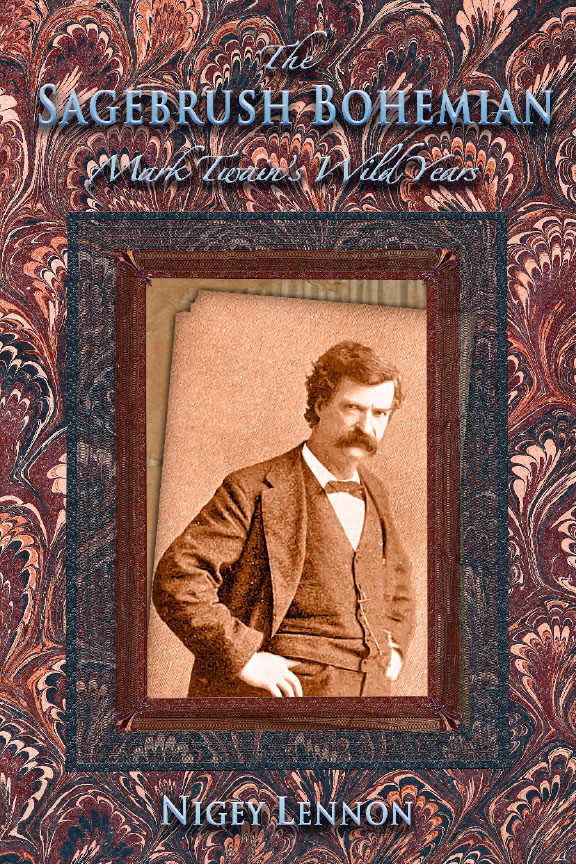

The

S AGEBRUSH B OHEMIAN

Mark Twains Wild Years

N IGEY L ENNON

A IRSTREAM B OOKS

N ORTHPORT, NY

First electronic edition, 2011

Published by AirStream Books

PO Box 383

Northport, NY 11768

Distributed by SCB Distributors

Copyright 2011 by Nigey Lennon

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in

any form, without written permission from the publisher, unless

by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages.

ISBN 978-0-9834884-2-2

Cover design by Heidi Kaestner

Spot illustrations by Anthony Mostrom

Dedicated to Eric (The Scanmeister) Weaver, with much love

Contents

What a wee little part of a persons life are his acts and his words! His real life is led in his head, and is known to none but himself. All day long, and every day, the mill of his brain is grinding, and his tfaughts, not those other things, are his history. His acts and his words are merely the visible, thin crust of his world, with its scattered snow summits and its vacant wastes of waterand they are so trifling a part of his bulk! a mere skin enveloping it. The mass of him is hiddenit and its volcanic fires that toss and boil, and never rest, night nor day. These are his life, and they are not written, and cannot be written. Every day would make a whole book of eighty thousand wordsthree hundred and sixty five books a year. Biographies are but the clothes and buttons of the manthe biography of the man himself cannot be written.

Mark Twains Autobiography

Get the facts first, and then you can distort them as much as you like.

Mark Twain

Preface

I first became aware of Mark Twain, and, hazily, of his intrinsic Westernness, when I was living in London in 1973. My mother, a war bride, had grown up in England, but I was born in California and spent my childhood there and in Arizona, and for me the European experience was like being on Mars. I found the weather uncongenial, the cultural advantages overrated, and the lack of reliable heating and modern sanitary facilities dismal. Had I been a few years older, I might have found some roses amid the thorns, but at eighteen I was still at an age where things like cheeseburgers and Hank Williams rode roughshod over history and philosophy.

That autumn I came down with a pesky virus that chained me to the bed in my unheated bedroom. I was too cold and shaky to get out of bed, so when I saw a battered old book propping up my decrepit bedside table, I seized on it with an almost pathetic avidity.

It was a copy of Mark Twains The Innocents Abroad, his first full-length book (as opposed to The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, which was a book comprised of short sketches). The Innocents describes Twains progress through Europe and the Middle East when he was a young barbarian fresh from the wilds of Nevada and California. I had read Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn as a child, but this was my first exposure to the adult Twain. I devoured the book in a few hilarious hours, and as soon as I was on my feet again, I headed for the West Hampstead public library, where there happened to be a five-foot shelf of Routledge and Camden Hotten editions of Twain from the previous century. I checked out as many of them as I could at one time, read them with gusto, and came back for more. By the time I left London I had hidden in my unconscious a vast quantity of half-digested Twain, and when I returned home to Los Angeles and became a free-lance writer, it continued to writhe and seep and seethe like yeast in bread dough. I had never stopped to think that the Mark Twain of The Innocents Abroad was, as a brash, uncultured Westerner in Europe, a lot like I was when I lived near Covent Garden and the British Museum but could only think longingly of the paradise lost of double-thick milkshakes and central heating. But the intuition was there, somewhere, and it was significant.

Some years later I was commissioned by a San Francisco publisher to write a short book on Twains California years. By then I had long since exhausted Twains own writing and had been forced to turn to his laundry lists and other scholarly minutiae, and I supposed I was as capable as anyone of composing an entertaining, reasonably factual, narrative of this period of his life. I rolled up my sleeves and went to work.

I had imagined that, given Twains reputation as the Lincoln of our literature, someone would have already written a book about his Western period, since it was so formative. I quickly discovered that since his death in 1910 the scholars had pounced on Twains literary and biographical corpus and had flung the pieces far and wide, covering a great deal of territory, but not the area in which I was interested. Biographers had, it was true, written books, articles, or parts of books and articles about Twain in Nevada, Twain as a San Francisco newspaperman, Twain as a public lecturer, Twain as a public nuisance, Twain and Bret Harte, and so on. But these were, to my way of thinking, unrelated parts of a larger whole. The more I read, the more I became convinced that there were conclusions to be reached about Twains Western years, and that no one had reached far enough to get at what seemed increasingly obvious to methe fact that although Mark Twain was born in the Midwest and lived more than half his life in the East, he was a Westerner first and foremost, having spent his formative years in Nevada and California. This was important, I felt, because of the tremendous impact Twain had exerted on nineteenth- and twentieth-century writing and thinking. His blustery, empirical Western spirit had liberated American literature from the parlor politesse of Henry and William James, Edith Wharton, and the like, clearing the path for writers like Jack London and Ernest Hemingway, among others.

As I worked on my research, I noticed a number of consistencies. One was the rather obvious fact that East Coast-based writers, and even Twains authorized biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine, tended to slight their subjects Western years. They couldnt skip them completely, since Twain became a professional journalist in Nevada, began his formal lecturing career in San Francisco, published his first two books using material gleaned during the time he was based in California, established a national literary reputation from the West Coast, and collected impressions and experiences in Nevada and California that were vital to his later workbut they certainly tried. In Paines three-volume biography, published in 1912, about three-quarters of one volume of them is devoted to the Western decade. Paine apparently skittered over this material in a rush to get his subject away from the barbaric frontier and safely married in Connecticut. Paine was a thorough and sympathetic biographer, but his plutocratic background made it difficult for him to understand Twains socio-political legacy as a writer of the people; and his New England sensibility plainly shuddered at the notion of Twain as the Bohemian from the sagebrush.

Paines biography remained the standard for a number of years; then Van Wyck Brooks came along in the 1920s with The Ordeal of Mark Twain. Brooks was the first of the Twain critics (he was a critic rather than a biographer) to utilize a crude sort of Freudianism on his subject. He reduced Twain to an infantile personality, and accused him of remaining perennially mired in adolescence.

Next page

![Twain Mark - Autobiography of Mark Twain Vol. 1 / associate eds. Benjamin Griffin ... [et al.]](/uploads/posts/book/210276/thumbs/twain-mark-autobiography-of-mark-twain-vol-1.jpg)