Contents

Guide

Page List

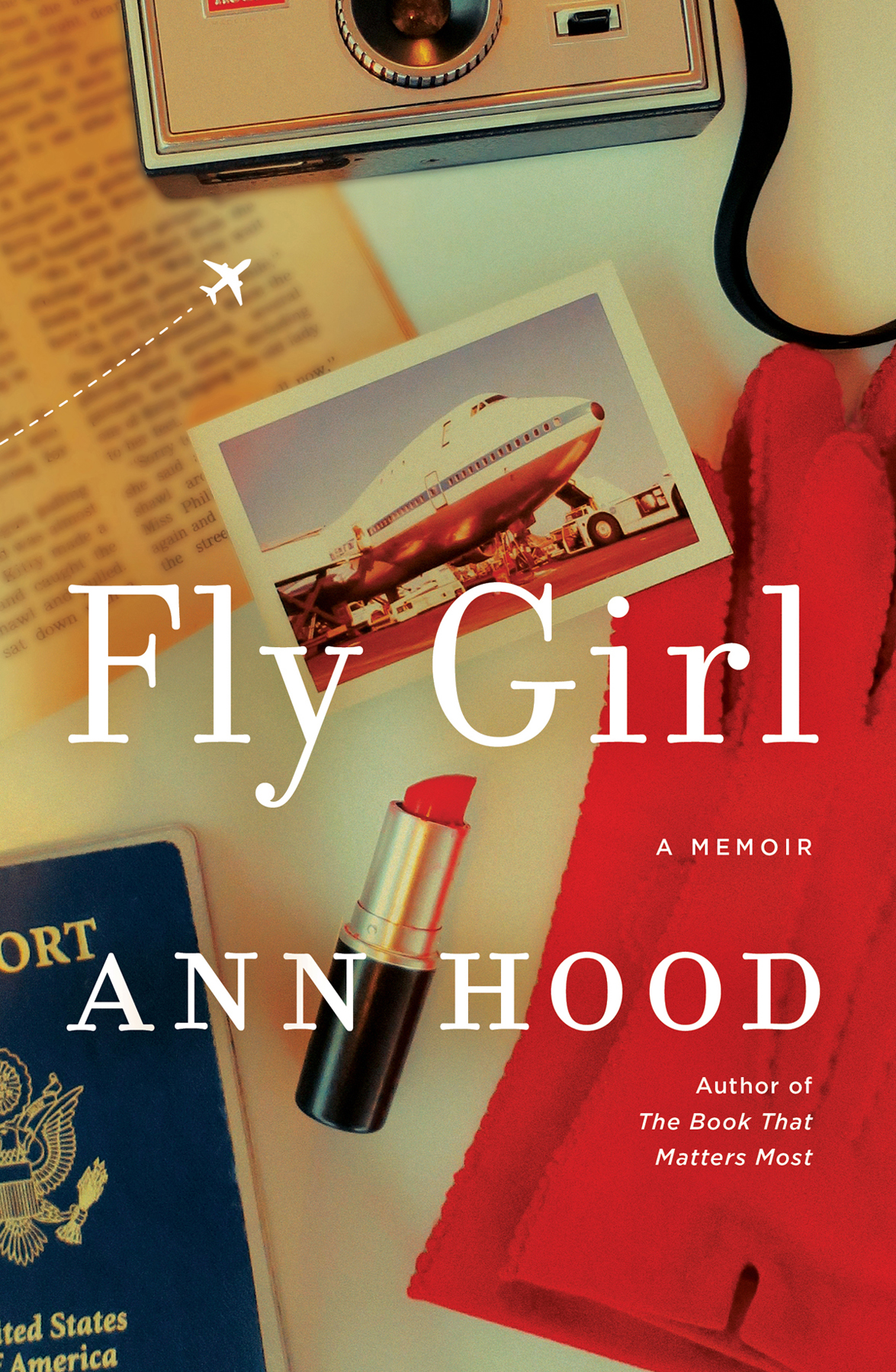

A Memoir

Ann Hood

For Kate Heckman

and

Matt Davies

CONTENTS

A FRIEND OF MINE recently said to me, I love when you start a story with When I was a flight attendant... because I know its going to be a good story. At dinner or cocktail parties, when someone asks what I do, they often look at me blankly when I say that Im a writer. Have I read anything by you? they ask, often accompanied with a narrowing of the eyes. Or: Have you published anything? Sometimes even people I know ask me if Im still writing, as if its a hobby and not a career. But once I say those magic words, When I was a flight attendant... everyone is interested.

What did I actually do on those planes? What was the scariest thing that ever happened? The weirdest? Was the job fun or boring? Did I actually get to see any of the places where I flew? Was there really a mile-high club? Did I date pilots? Passengers? Famous people? Flight attendants still hold the mystique they had back in the golden age of flying, even though, as one flight attendant described it, I started to fly when every passenger was treated like they were in first class, and stopped flying when most passengers felt like they were riding a Greyhound bus, not a jumbo jet. I have the unique experience of starting as a flight attendant at the end of those glamour days, and stopping just as service, legroom, and meals began to disappear. I flew through the start of deregulation, an oil crisis, massive furloughs, start-up airlines, corporate takeovers, and a labor strike. I didnt see it all, but I saw a lot.

Why did I, a smart, twenty-one-year-old woman in 1978 choose to become a flight attendant rather than a banker or pharmaceutical salesperson or teacher or social worker as my college friends had? Flight attendants were still stereotyped as not-very-smart sex kittens in airline advertising and in many peoples minds back then. Yet the only job I applied for during my senior year of college was flight attendant.

The love of flying, the romantic connotations of flight, the dreams of adventure were planted in me when I was very young. I literally and metaphorically had my eyes on the sky. At night, in 1958 or 59, in Arlington, Virginia, at the Shirley Park Apartments, we kids sat on the grassy hill between the apartment buildings and stared up at the sky to watch spotlights sweep across it. A new airport, so modern that moving pods would take passengers to their airplanes, was being built. I dont know why those lights swept the sky sometimes, but when they did it was always an event. Our parents hustled us outside and everyone lay down on blankets and watched.

A year or two earlier, the Russians had launched Sputnik into space, where it had orbited for a couple months, looking down at us. Although I was too young to remember that, ever since it happened, all everyone talked about was spacegoing into it, imagining what was there, landing on the moon like President Kennedy promised wed do. It was no wonder that I became fascinated, obsessed even, by the idea that something was up there, circling, watching, seeing. Seeing what? Stars, certainly. Planetsthe rings of Saturn, angry red Mars, comets with their flaming tails. The moon that was possibly made of blue cheese, or maybe was an actual face staring down on us. See the Man in the Moon? my mother would ask, her finger pointing out the wavy eyes and grin. But what else? Martians? Angels? Saints? I thought about the sky. What was it made of? Could I stand on its clouds? I took to gazing upward.

The year after I was born, the Russians launched a dog named Laika into space in Sputnik 2 to see if it was possible to survive being launched into space in a rocket. Laika died six days later because she ran out of oxygen. (Or so we thought; half a century later we learned shed actually died within hours.) We didnt hear much about Laikas fate, just that the Russians were ahead of us in the Space Race. Laika was a folk hero of sorts, like Lassie and Rin Tin Tin, and kids whispered about her with a combination of awe and sadness for years after she went to space. The Russians had launched a satellite, too, Sputnik 1, and the adults worried over the implications of the Russians beating us into space. But I thought of Laika as I watched the sky on those autumn nights. I thought of space and rockets and moving pods. The year I was three, and again the next year, I dressed as a space girl for Halloween. My mother used aluminum foil to make the costume, adding pipe cleaner antennae to the top of my head because no one really knew what a space girl might look like.

Sometimes on Sunday afternoons we drove out to Chantilly, Virginia, twenty miles from the Shirley Park Apartments, to watch them work on the new airport. We parked our enormous green Chevy station wagon in an empty field and stared out at the cranes and construction equipment, oddly excited. My father knew everything about the airport. The architect, he told us, was Eero Saarinen, and he was from Finland. The airport was being built to accommodate new airplanes called jets. They had big enginestwo on each winginstead of propellers and, my father told us, they were going to change the world. A person could get on a jet at this airport, he said, sweeping his arms toward the piles of concrete and equipment, and be in Paris France in seven hours. That was less time than it took us to drive to visit my grandmother in Rhode Island.

And then, the most exciting thing of all happened. On October 17, 1958, President Eisenhower christened the first Boeing 707 at the other airport in Washington, DCNational Airport. That was followed by the first flight of a 707 jet, a VIP-only trip from Baltimores Friendship International Airport to Le Bourget in Paris, with a stop to refuel in Gander, Newfoundland. It is no exaggeration to say that this was all people talked about. Jets. Progress. Tomorrowland come to life.

Once again, all of the children in the Shirley Park Apartments were hustled outside. Down the stairs from our second-floor apartment, out the door, onto the grass. Watch the sky! our parents instructed, their necks craned, their eyes gazing upward. I, too, dropped my head back and set my sight on the blue, blue sky. It seemed that for a very long time there was just that blue sky and puffy white clouds. Until in the distance came a rumbling and all of the parents pointed to the sky and the jet cut across it, leaving a long white tail behind. Even after the 707 disappeared, that tail of white remained. I remember staring at it until it disappeared, a habit I still have today.

Although it can be argued that the Jet Age began a week later, when a Pan Am 707 took off from Idlewild Airportnow JFKin New York, headed to Paris on its first daily scheduled flight, for me the Jet Age began the day I watched that Boeing 707 cut across a Virginia sky.

Five months later, TWA followed Pan Am with its first regularly scheduled jet flight from San Francisco to New York. That flight took five and a half hours, half the time it had taken on the Constellation prop planes. Soon, Boeing 707s dominated air travel, and led to changes in everything about it, from airport runways and catering to baggage handling and air traffic control systems. By 1970, Boeing had to create a new, bigger jetthe 747to accommodate the growth of air travel that the 707 had begun.