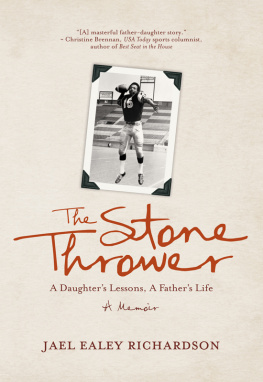

Do Not Go Gentle

My Search for Miracles in a Cynical Time

Ann Hood

for my father

prologue

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

DYLAN THOMAS

EVER SINCE I STARTED to write professionally, I would tell my parents the plots and characters I had dreamed up. My mother always listened attentively, then said, That sounds like a good story. Shed wait a minute and then add, Next time, why dont you write about the family. Why dont you write about my sister Ann, and how she fell in love so young and died so tragically? Or about Nonna and the things she could do, that no one can explain? Then she would sigh. There are so many things right here, shed say.

I always smiled and told her that was a good idea. But I didnt really believe it was a good idea.

I grew up Catholic in an Italian-American family in a small mill town in Rhode Island. At the heart of my family lay an unwavering faith in the power of things larger than ourselves. Sometimes this faith took the shape of traditions and superstitions brought over from the Old Country with my great-grandmother at the turn of the century. Sometimes it reflected beliefs of the Catholic Church, of which we were members and believers in its doctrine. And sometimes this faiths roots lay in family, in the strength and closeness that comes from a shared history, a shared home, a love that has no greater match.

Despite the usual falling away from faith that one suffers as time and experience intrude, I mostly held on to the same strong faith that my great-grandmother and grandmother and mother passed on to me. That faith gave me strength and hope and optimism. It kept me from loneliness and even despair. It was a faith that allowed me to believe in possibility, in goodness, and in miracles.

Then, on a beautiful September day in 1996, a series of events began that put my faith to a test. One day, in the midst of those events, as my father lay sick in the hospital, he took my hand and looked me right in the eye.

Whats all this supposed to mean? he asked me.

What?

He shrugged. All of it, he said.

We sat quietly for a moment, then he said, Youre a writer. When this is all done, figure it out and tell the world this story.

I did not know that by taking my fathers advice to tell this story, I would also do what my mother had suggested for years: tell all of our stories. W. R. Inge wrote that every person makes two journeys in life. The outer journey is full of various incidents and milestones as we pass through our youth and middle age. The second is the inner journey, a spiritual Odyssey, with a secret history all its own. This is the story of my spiritual Odyssey.

1

the dream

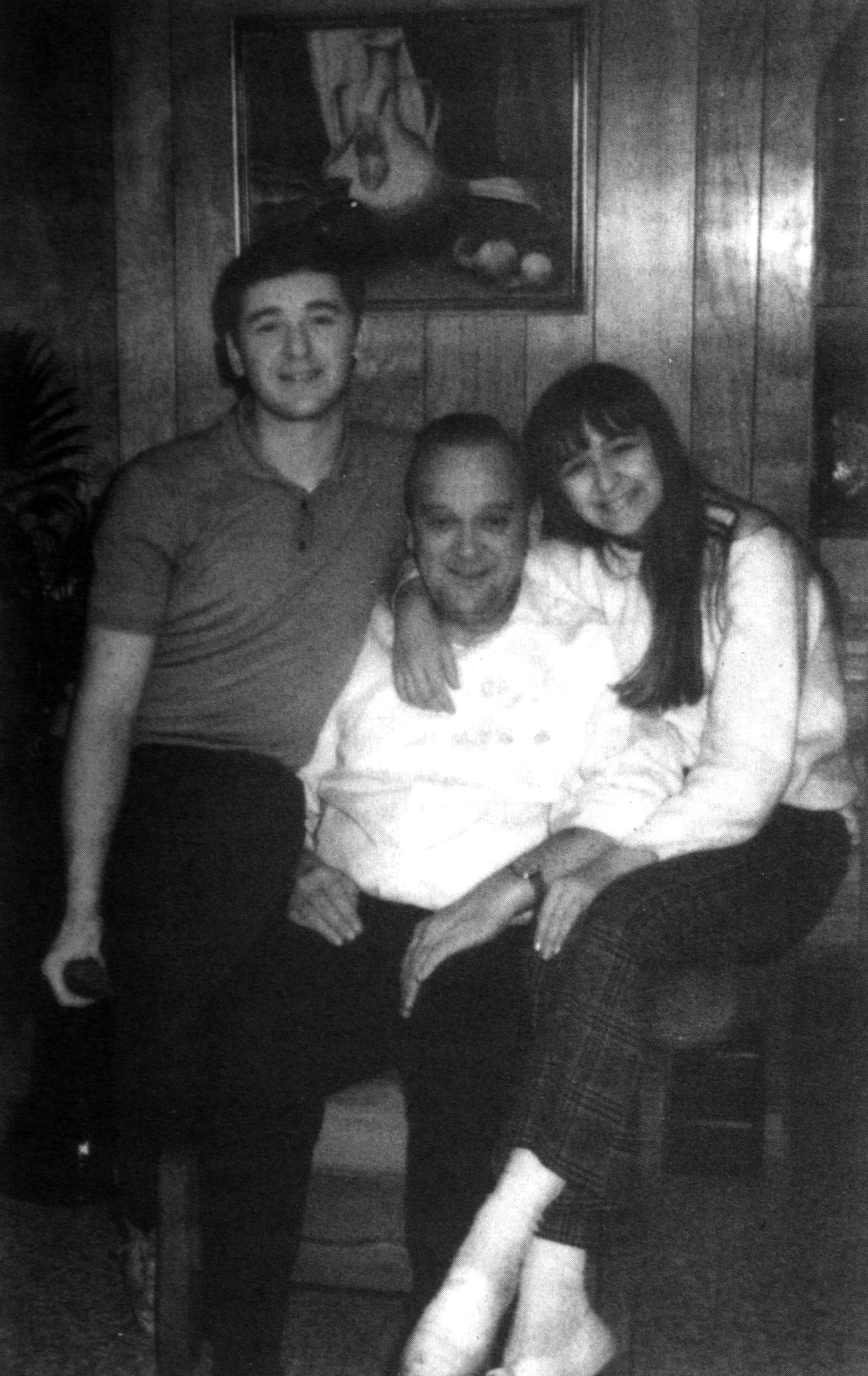

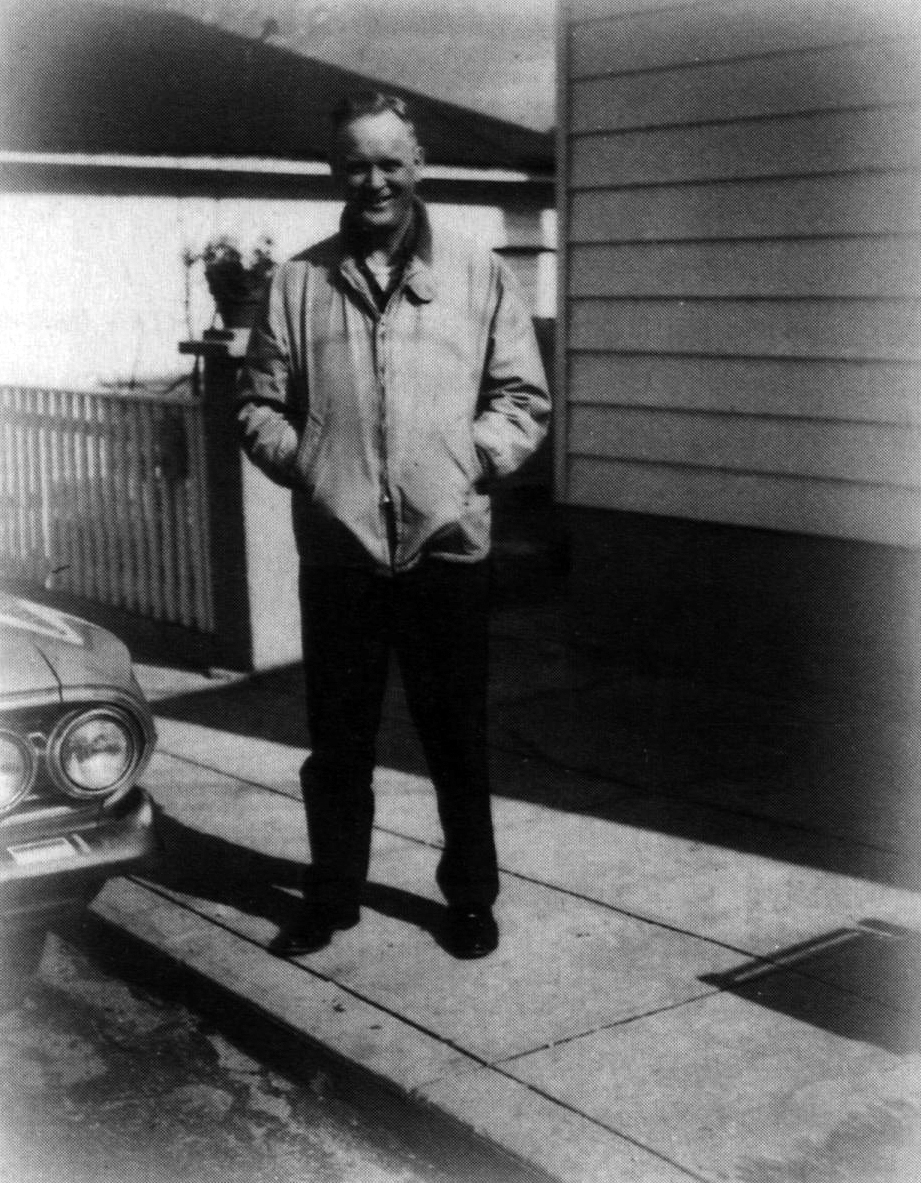

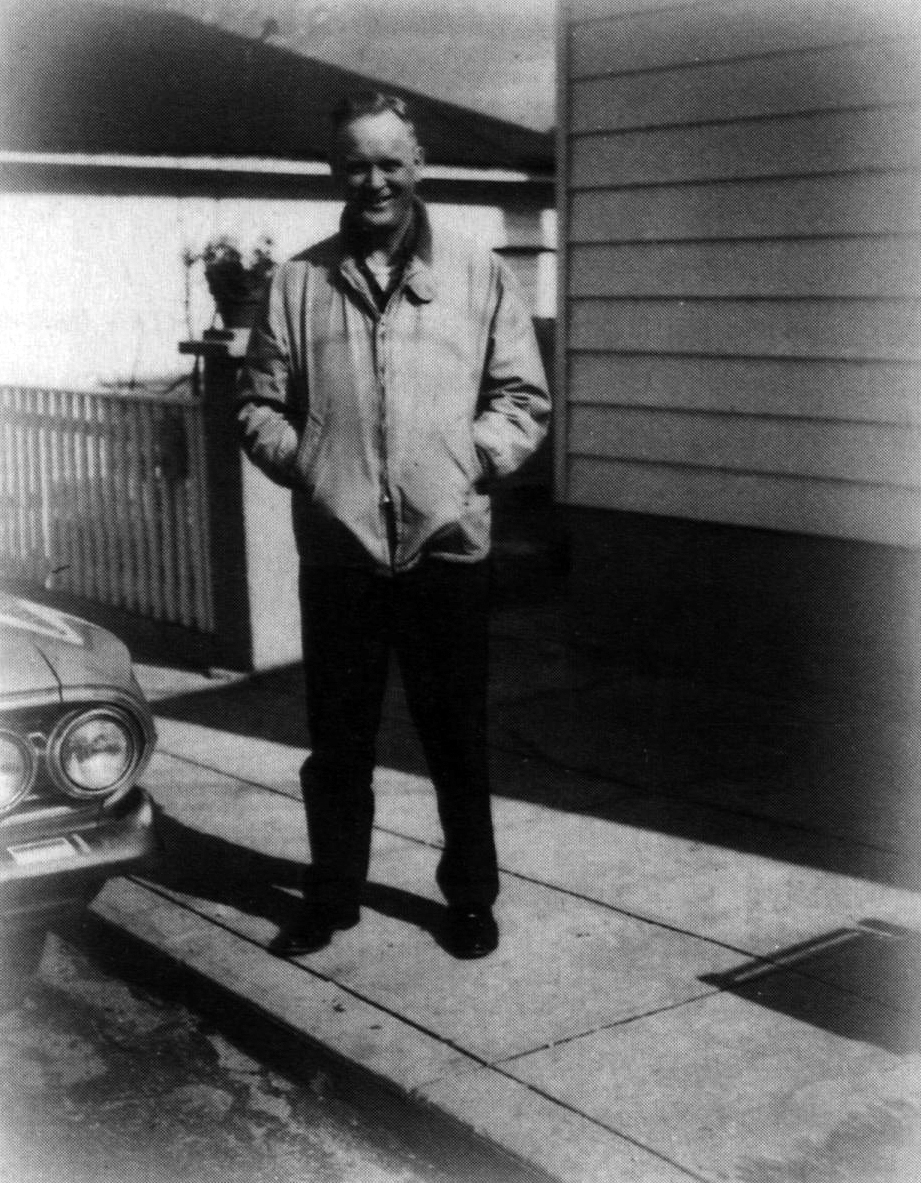

THE DAY MY FATHER was diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer, I decided to go and find him a miracle. My family had already spent a good part of that autumn of 1996 chasing medical options, and what we discovered was not hopeful. Given our odds, a miracle cure did not seem too far-fetched. Eight years earlier, my father had given up smoking after forty years of two packs a day, and he had promptly been diagnosed with emphysema. Despite yearly bouts of pneumonia and periodic shortness of breath, he was a robust sixty-seven-year-old. Robust enough to take care of my young son Sam and, since he had retired, to cook and clean the house he and my mother had lived in for their forty-five years of marriage, while my sixty-five-year-old mother continued to work at the job she loved.

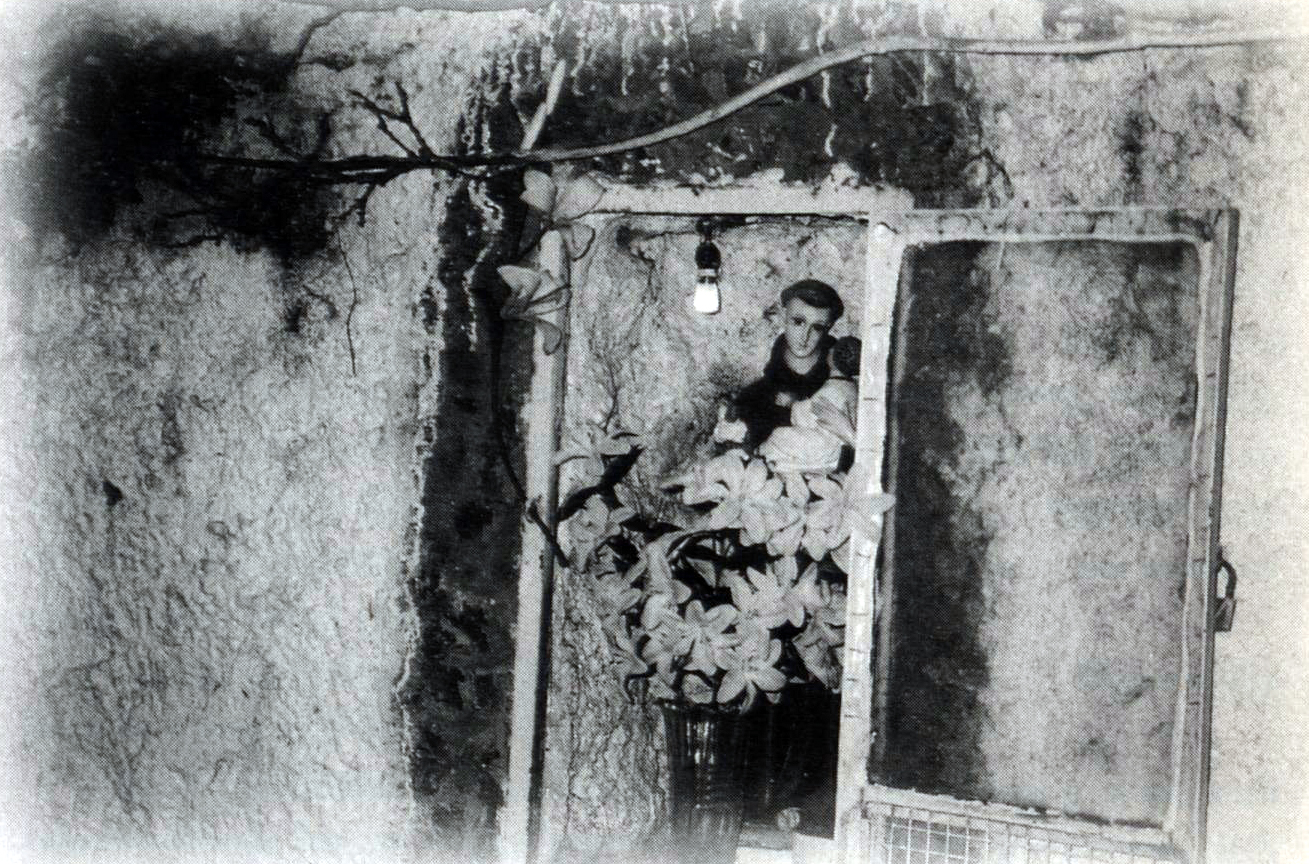

The house has been in my mothers family for three generations. It is a hybrid of styles and designs: The panelled walls and aluminum siding arrived in the sixties, but the pear and fig trees that grow in the backyard were planted by my great-grandmother at the turn of the century. It was her husband who dug the dirt cellar to store his homemade wine. Now that cellar holds everything from the steamer trunks my great-grandparents used when they moved to Rhode Island from Italy to my brothers long-ago-abandoned surfboard and my own Barbie nestled in her moldy lavender case.

We are a superstitious family, skeptical of medicine and believers in omens, potions, and the power of prayer. The week the first X ray showed a spot on my fathers lung, three of us had dreams that could only be read as portentous. I dreamed of my maternal grandmother, Mama Rose.

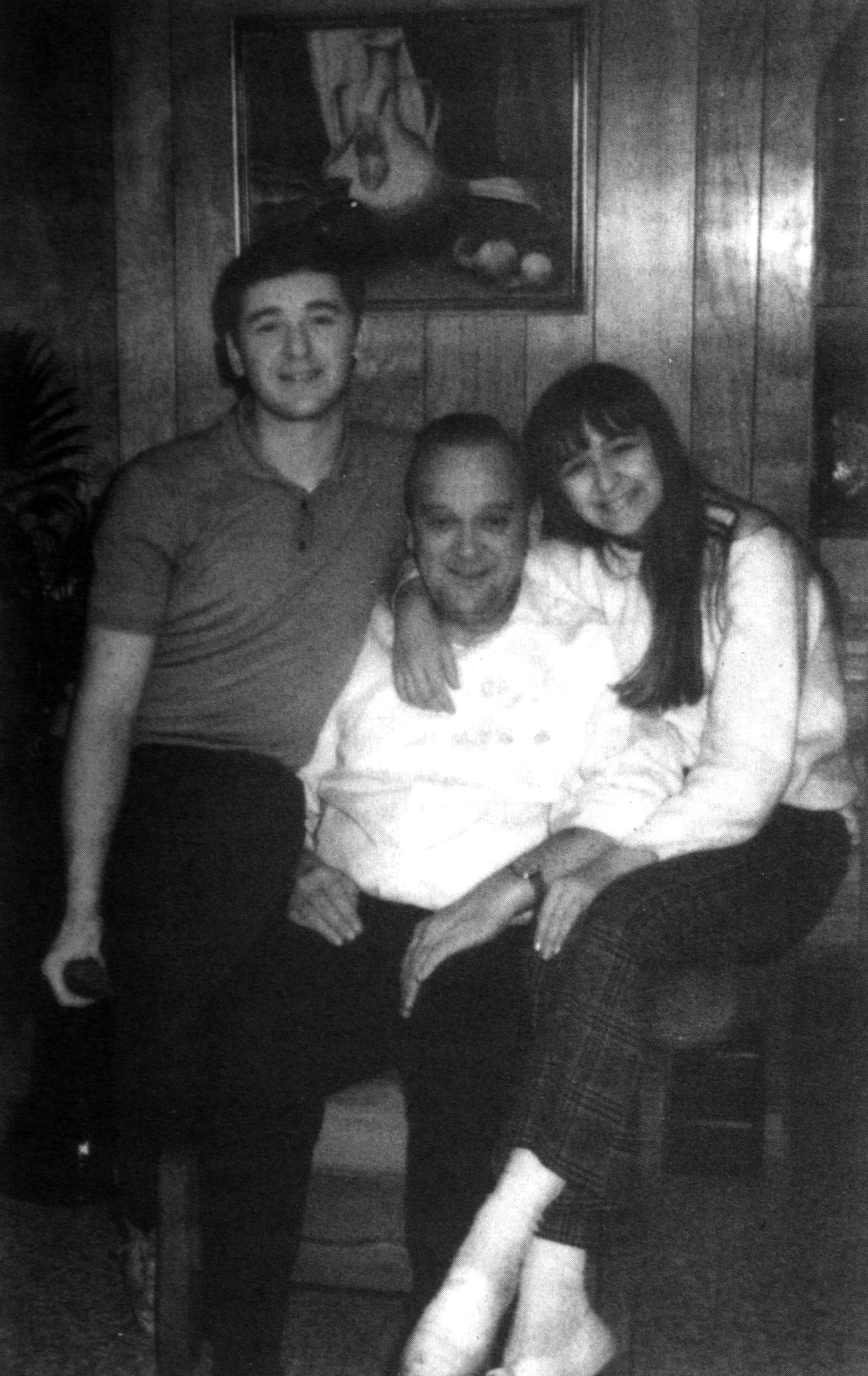

I had good reason to distrust my grandmother. Mama Rose stood four feet ten and had ten children, twenty-one grandchildren, and flaming red hair until the day she died at the age of seventy-eight. She liked Elvis Presley, the Old Countrya small village in southern ItalyAs the World Turns, and going into the woods to collect wild mushrooms. What she didnt like was me. This wouldnt have been a problem except that she lived with my family and so every day became a battleground for us.

Although my parents had technically bought our house from her back in 1964, Mama Rose never really let it go. She had, after all, lived there since she was two, except for three years in Italy recovering from a bout of scarlet fever. Despite her limited time in the Old Country, Mama Rose acquired a thick Italian accent sprinkled with mispronounced words, her favorite being Jesus Crest! As an only child, the small three-bedroom house had suited her fine as she grew up. Until the day she died she had the same bedroom shed had as a girl. The only changes were in her roommates: her husband, Tony, after he died her youngest daughter, June, and after June got married and our family moved in, me.

Already slightly afraid of her, I begged for a different bedroom. Where do you want to go? my mother would ask me, exasperated. My father was in the navy and after moving us back to Rhode Island was promptly shipped off to Cuba, an assignment that did not allow families. My mother had to find room for herself, my ten-year-old brother, and me, who was five. Upstairs, my great-grandmother was still in the room shed occupied for the last sixty years. My mother moved back into her old bedroom, the same one shed shared with her five sisters. And my brother was in the tiny former storage room that my three uncles shared as children.

Of course, Mama Rose offered, you could sleep there. There was a beat-up green couch in the kitchen that Auntie June had slept on until after her father died and she moved in with Mama Rose. To me, that couch held nightmares and ghosts. My strongest memory of it was when I was three and my Uncle Brownie died. Mama Rose lay there all day screaming and pulling her hair. I eyed the green couch and mumbled, No thanks.