John

Laurens

and the

American

Revolution

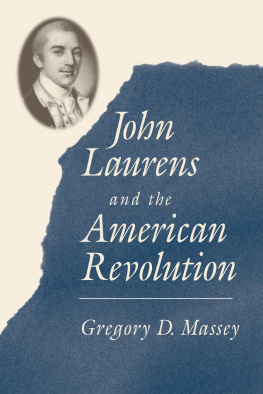

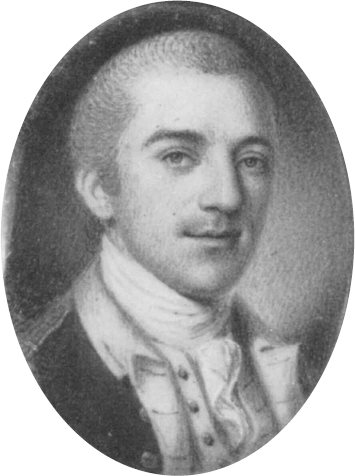

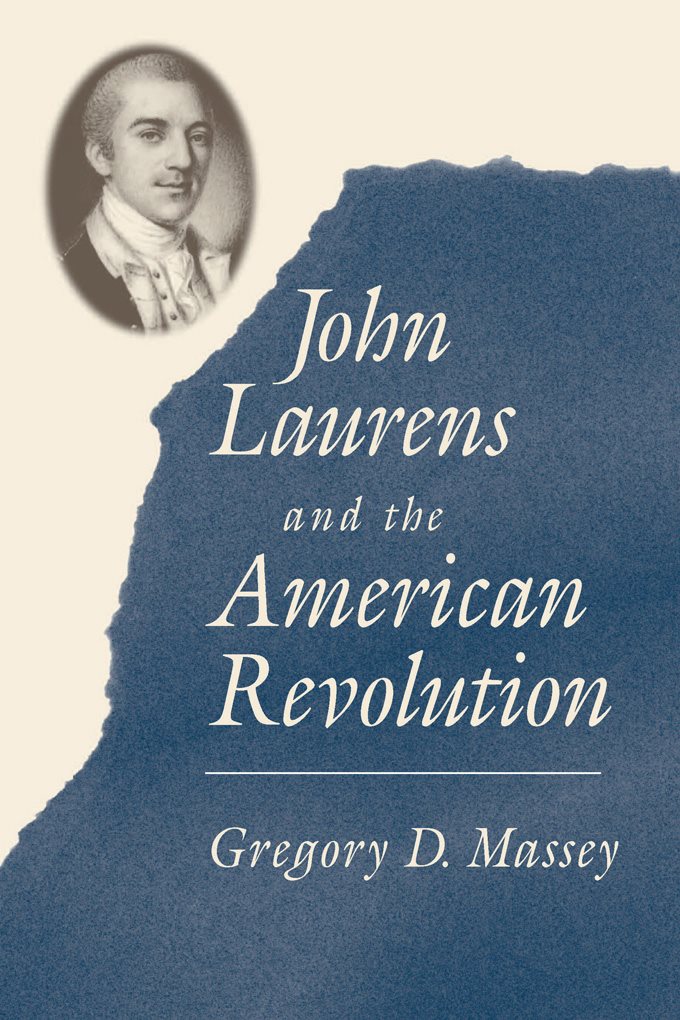

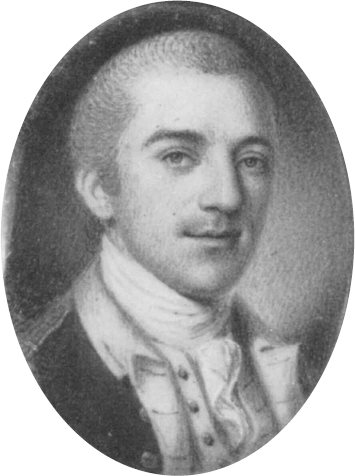

Portrait of John Laurens

John

Laurens

and the

American

Revolution

Gregory D. Massey

The University of South Carolina Press

2000 University of South Carolina

Cloth edition published by the University of South Carolina Press, 2000

Paperback edition published by the University of South Carolina Press, 2015

Ebook edition published in Columbia, South Carolina, by the University of South Carolina Press, 2016

www.sc.edu/uscpress

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition as follows:

Massey, Gregory De Van.

John Laurens and the American Revolution / Gregory D. Massey.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-57003-330-7 (alk. paper)

1. Laurens, John, 17541782. 2. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783. 3. SoldiersUnited StatesBiography. 4. United States. Continental ArmyBiography. I. Title.

E207.L37 M38 2000

973.3'092dc2199-050753

ISBN 978-1-61117-612-4 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-61117-613-1 (ebook)

Front cover art & frontispiece: Portrait of John Laurens, a miniature painted by Charles Willson Peale in 1780, watercolor on ivory. Privately owned. On deposit at Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association, Charleston.

For Van S. Massey,

and in memory of

Helen P. Massey

Contents

Illustrations

Portraits

Maps

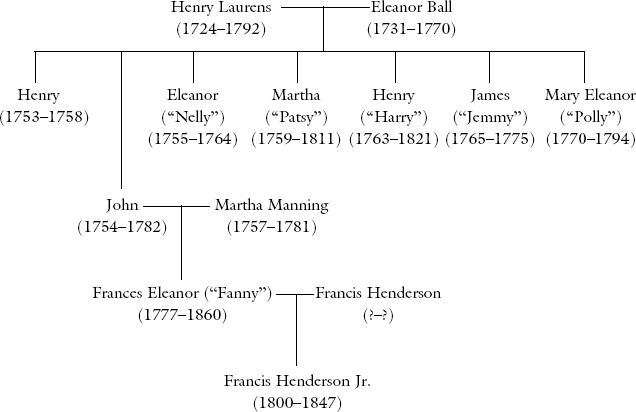

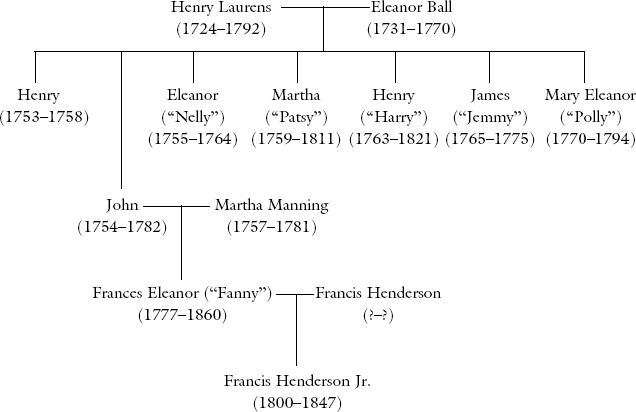

Family Line of John Laurens

Preface

History involves historians examining surviving sources and then selecting evidence and using it to write narratives that illuminate the past, describing it while never quite definitively capturing it. So much of the past remains unknowable, lost to us because of the lack of sources, lost to us also because we can not read the minds and discern the motives of those who left behind written traces of their lives. So it is with John Laurens. In his short, tempestuous, and exciting life, he left behind tangible evidence of his actions and motivations in his correspondence, and the historian has access also to the observations of his contemporaries, but our knowledge of him, as of any historical figure, will always remain provisional. When I was working on this book nearly two decades ago, I wanted to write a narrative that would engage the reader in Laurenss exciting life. Thinking it would improve the books readability, I made a conscious decision to write decisively about this very decisive and impulsive historical figure, which meant that I often resisted using qualifiers such as maybe or perhaps, particularly in assessing his motivations, and in deciphering what factors influenced his repeated reckless behavior. In retrospect, I realize that the choice to make decisive statements sometimes drained the book of one of historys most mysterious and enduring qualities: that so much of our knowledge of the past is provisional and ultimately unknowable. And I issue now a disclaimer that did not appear in the books first edition: My arguments about the factors that influenced Laurens to be impetuous in public and private life are more conjectural than my language makes them appear. I believe that I come close to capturing the tension between aspirations and achievements that so shaped Laurenss choices, but ultimately he, like any figure of the past, will always remain slightly beyond the historians grasp.

Revision is an essential part of the historical process. Not surprisingly, historians sometimes revise their own views or wish they could revise things they have written. If I had the opportunity for a do-over, there are three areas of my biography of John Laurens that I would change. In chronological order they are the presentation of the John Laurens-Alexander Hamilton relationship, the account of the siege of Savannah, and the assessment of Laurenss diplomatic mission to France. In retrospect, I should have been equivocal rather than decisive in asserting that the Laurens-Hamilton friendship was platonic. Whether or not their relationship was homosocial or homosexual is a matter of debate that can not be definitively resolved. I wish I had read in its entirety the Count dEstaings journal of the siege of Savannah. It is reprinted in Benjamin Kennedy, Muskets, Cannon Balls, & Bombs: Nine Narratives of the Siege of Savannah (Savannah: Beehive Press, 1974), a book I discovered after my own work was published. Upon reading the full journal, including dEstaings description of Laurenss Continentals fleeing at the first musket volley fired by the British, I realized that accounts of Laurenss self-destructive behavior on that day were more explicable, as his personal honor had been deeply wounded. Finally, the publication of volumes 34 and 35 of Barbara B. Oberg, et al., eds., The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 19992000), provides evidence that Laurenss mission to France played a decisive, contingent role in French naval planning for the 1781 campaign. Laurens, in other words, deserves more credit for the French naval cooperation that led to the victory at Yorktown than I gave him in this book.

These points aside, I am pleased that the University of South Carolina Press is releasing a paperback edition of this book and hope it will introduce new readers to the Laurens family, one of the enduringly fascinating families of the era of the American Revolution, and to John Laurens, an exciting, flawed, but ultimately attractive and tragic figure.

Acknowledgments

Much of the historians craft involves long hours of individual labor. On occasion, fortunately, the moments of solitude are punctuated by collaboration with others. It is a pleasure to extend appreciation to the people who helped me bring this project to completion.

Robert M. Weir directed this study in its original form as a doctoral dissertation. His historical imagination and resourceful intellect focused my attention on questions I otherwise might have overlooked. It is a testimony to Professor Weirs talents as a scholar that after extensive research, involving repeated efforts to find holes in his own essay on John LaurensI wanted to avoid the appearance of merely parroting that workthat this book corroborates the principal conclusions in his exploratory essay. I would like to thank other scholars at the University of South Carolina: Owen Connelly, who commented on the dissertation; Ronald Maris, who provided insights into selfdestructive behavior; Kendrick Clements, who read the sections on revolutionary diplomacy; and Samuel Smith, who allowed me to cite his unpublished work on Henry Laurenss religious views.

Without the assistance of the staff of the Papers of Henry Laurens, this study would not have been possible. I owe more than I can express to David Chesnutt, Jim Taylor, and Peggy Clark, who provided me access to their archivesand coffee roomand read an earlier draft of the manuscript and saved me from numerous errors. Two people I met at the Laurens Papers project deserve special mention. The late George C. Rogers Jr. allowed me to use his extensive research files and library; in addition, he read and commented on multiple drafts of the manuscript. Georges civility and generosity, his enthusiasm for history and zest for life, will ever inspire those who were fortunate enough to have known him. Martha King read more drafts of this study than anyone else. On several occasions she directed me to John Laurens documents that I had not previously uncovered. Marthas editorial pen and historical sensitivity immeasurably improved the quality of this book and made me a better historian.

Next page