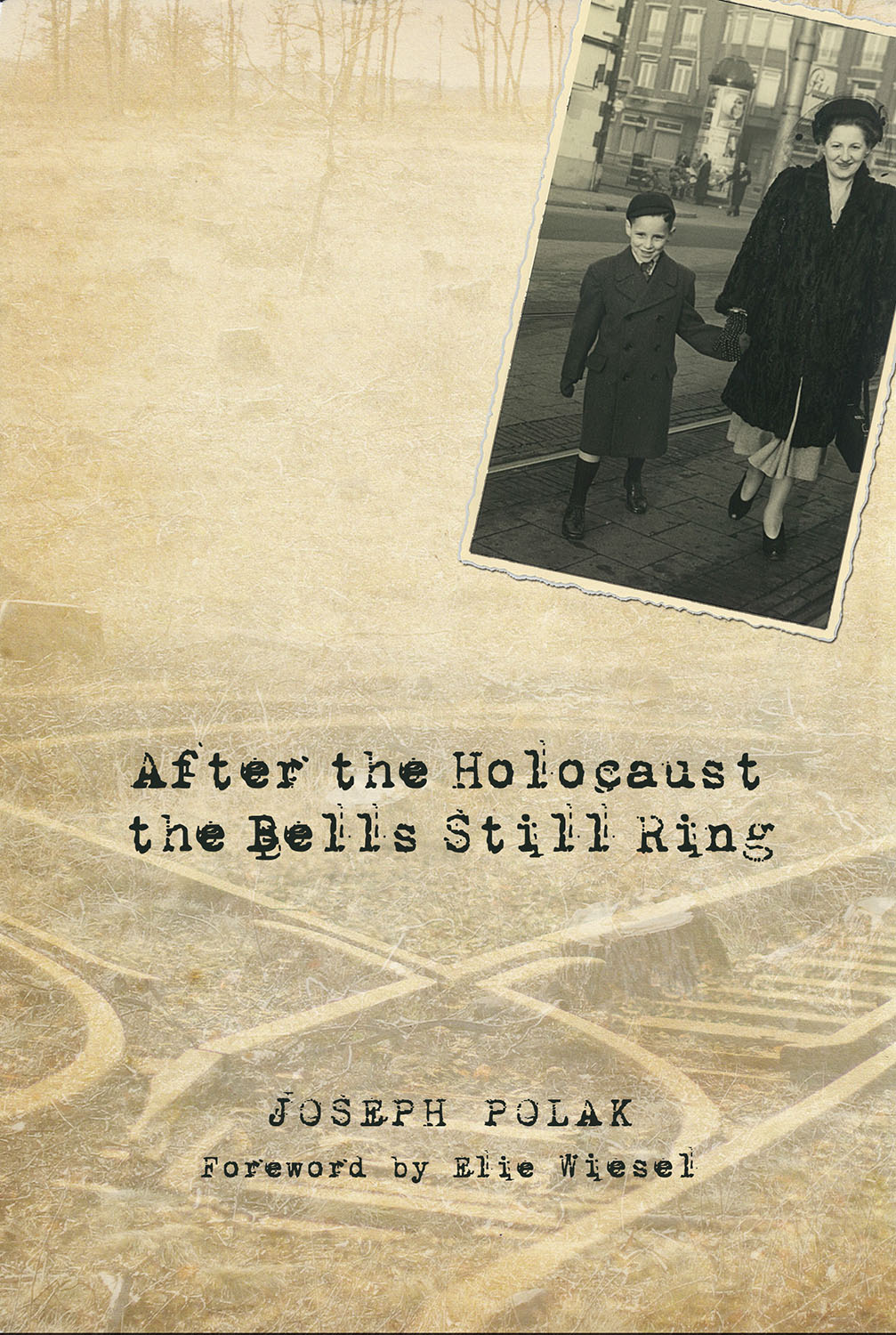

AFTER THE HOLOCAUST

THE BELLS STILL RING

AFTER THE

HOLOCAUST

THE BELLS

STILL RING

Joseph A. Polak

Foreword by Elie Wiesel

Urim Publications

Jerusalem New York

After the Holocaust the Bells Still Ring

by Joseph A. Polak

Copyright 2015 by Joseph A. Polak

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright owner, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews and articles.

ePub ISBN 978-965-524-225-6

Mobi ISBN 978-965-524-226-3

PDF ISBN 978-965-524-227-0

(Hardcover ISBN 978-965-524-162-4)

Cover design by the Virtual Paintbrush

ePub creation by Ariel Walden

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Polak, Joseph, 1942

After the Holocaust the bells still ring / Joseph Polak ; foreword by Elie

Wiesel. -- First edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-965-524-162-4 (hardcover : alkaline paper) 1. Polak, Joseph,

1942- 2. Jewish children in the Holocaust--Netherlands--Hague--Biography.

3. Jews--Netherlands--Hague--Biography. 4. Mother and

child--Netherlands--Hague--Biography. 5. Holocaust, Jewish

(1939-1945)--Netherlands--Hague--Personal narratives. 6. Westerbork

(Concentration camp) 7. Bergen-Belsen (Concentration camp) 8. Holocaust

survivors--Biography. 9. Polak, Joseph, 1942---Philosophy. 10.

Rabbis--Massachusetts--Boston--Biography. I. Title.

DS135.N6P65 2014

940.53'18092--dc23

[B]

2014031046

Urim Publications,

P.O. Box 52287, Jerusalem 9152102 Israel

www.UrimPublications.com

In memory of

Abraham Zuckerman

(19242013)

Holocaust survivor, Schindler Jew,

philanthropist, community builder,

loving husband, father and grandfather

Table of Contents

In which the author purports to describe the first attempt by the Nazi machine in The Hague, Netherlands, to deport him (at the time, a fetus), together with his mother and his father, to the East.

In which the author contemplates whether it might have been better not to have been born.

In which the author attempts to describe the conditions of his internment while still an infant in Westerbork, the Dutch transit camp, through which over a hundred thousand Dutch Jews passed on their way East.

In which the author, deported as a toddler (with family still intact) from Westerbork to Bergen-Belsen on February 1, 1944, considers the interaction of life and death in this place.

In which the author considers his journey from Bergen-Belsen to Theresienstadt in April, 1945, his liberation from the Nazis, the death of his father, his separation from his mother, and his adoption by a Dutch-Jewish family.

In which the author juxtaposes the lives of his parents who, in his memory, were never together.

In which the author considers the joy of living after the Holocaust.

In which the author describes the grip the Holocaust had on those of its victims that survived.

Plus a change, plus cest la meme chose.

Who is left to remember the Holocaust?

Foreword by Elie Wiesel

D istinguished colleague, charismatic teacher, lover of Jewish culture and tradition, Rabbi Joseph Polak sees himself above all as a survivor of Bergen-Belsen. His experiences as a child in occupied Europe affect his thinking as deeply as his loyalty to tradition.

During the several decades we spent together at Boston University, we fell into the practice of devoting several hours everyday delving deeply into a page of Talmud, into the ancient debates between the Sages, teasing out, as well, their meaning for today.

Learned, brilliant, with an insatiable intellectual curiosity, always open-minded, he knows how to pause in the middle of an obscure talmudic passage and there uncover an intellectual or ethical link to contemporary reality.

To study with him was for me more than a passing joy; it was a return to the past. With him to my right, or opposite me, the volume of Talmud open on the table, I once again was my adolescent self in my little village in Transylvania, in cheder , chanting the old passages written for us by our ancestors.

We rarely spoke of the war. Sometimes, though, it appeared, springing forth, uninvited, like a question one doesnt expect. How did our Sages find the strength and the means to fight the hate which surrounded them? What is the lesson that becomes our legacy from them? Faced with the questions confronting our generation that of Auschwitz, naturally what can we do to be faithful to them? How would they themselves have behaved in Birkenau?

A profound believer and scrupulously observant, he is fully admired and beloved by our students. They appreciate his desire to share his knowledge, his experiences and his intellectual and moral courage to challenge what is prohibited for the benefit of a great discussion. For him, as for me, a good answer does not replace a good question, but confers a new dimension upon it, transforms it into something different, more profound, further inaccessible, but also inexhaustible.

For all these, and for so many other reasons, writing the foreword for his book is far greater than a gesture; it is a confirmation that some encounters remain timeless.

They raise anew the human miracle.

Elie Wiesel

Summer,

(translated from the French by Martha Liptzin Hauptman)

Prologue

A lmost every year since 1 an annual conference of child survivors of the Holocaust has taken place. Typically, four to five hundred participants are in attendance, forming, among other possibilities, a kind of therapeutic community in which ones history may be reconsidered in a validating setting, where everyone is as afraid as you are of their past, where mourners may mourn their dead and, where necessary, their living, and receive a measure of consolation no other segment of society can offer. For many child survivors, the Gathering, as it is called, has become a pilgrimage, and for those working to organize it, a high point in their personal lives.

I have attended a few of these Gatherings, and in the fall of I was asked to address the plenum of this group , whose members had been through the Holocaust as toddlers and children. For this occasion I chose to read selections from this memoir. What follows in this prologue is what I said to them as an introduction to that reading . I can think of no better way to begin my story.

Ladies and Gentlemen:

We are gathered here, the children the children the last survivors of the Holocaust. We who played around the horrors of Bergen-Belsen, we who were hidden by loving parents who disappeared, often never to return. And if they did return, it was often with shame, with mindlessness, with madness, sometimes incapacitated emotionally and physically.

What could our surviving parents and guardians have been thinking, when, having seen what we saw, having lived in circumstances so depraved, so deprived that there is no historical parallel to them; what could they have had in mind when, at wars end, they placed us in regular schools, in regular camps, among regular children? On what basis did they think we would adapt, somehow which none of us did?

So many of us did not know how to eat normally, did not know how to play at all. Some of us knew love only from parents who we never saw again, or from adoptive families from whom we were seized after the war.

For many of us, the Holocaust only began after it ended in 1945.

It was only then that we became aware, and started to process what we had been through, what our families, if we had any left, had experienced. The 1950s, the decade of nocturnal screaming, the decade of social silence. The decade of everyone presuming that the Holocaust was behind us, that horror and evil could be put behind us. Two child survivors I know had their parents shot in front of them when they were ten years old, each in different Polish ghettos. How could anyone imagine that these children would get over it ?