Burtyrki Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

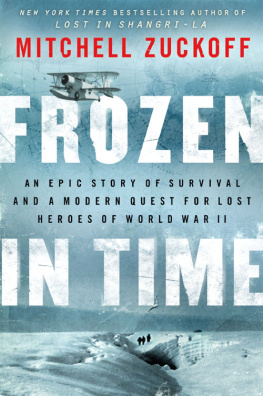

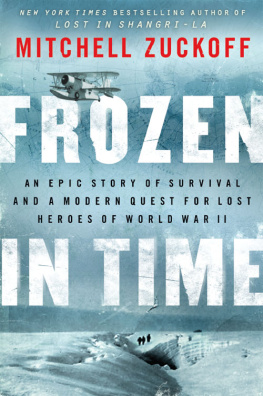

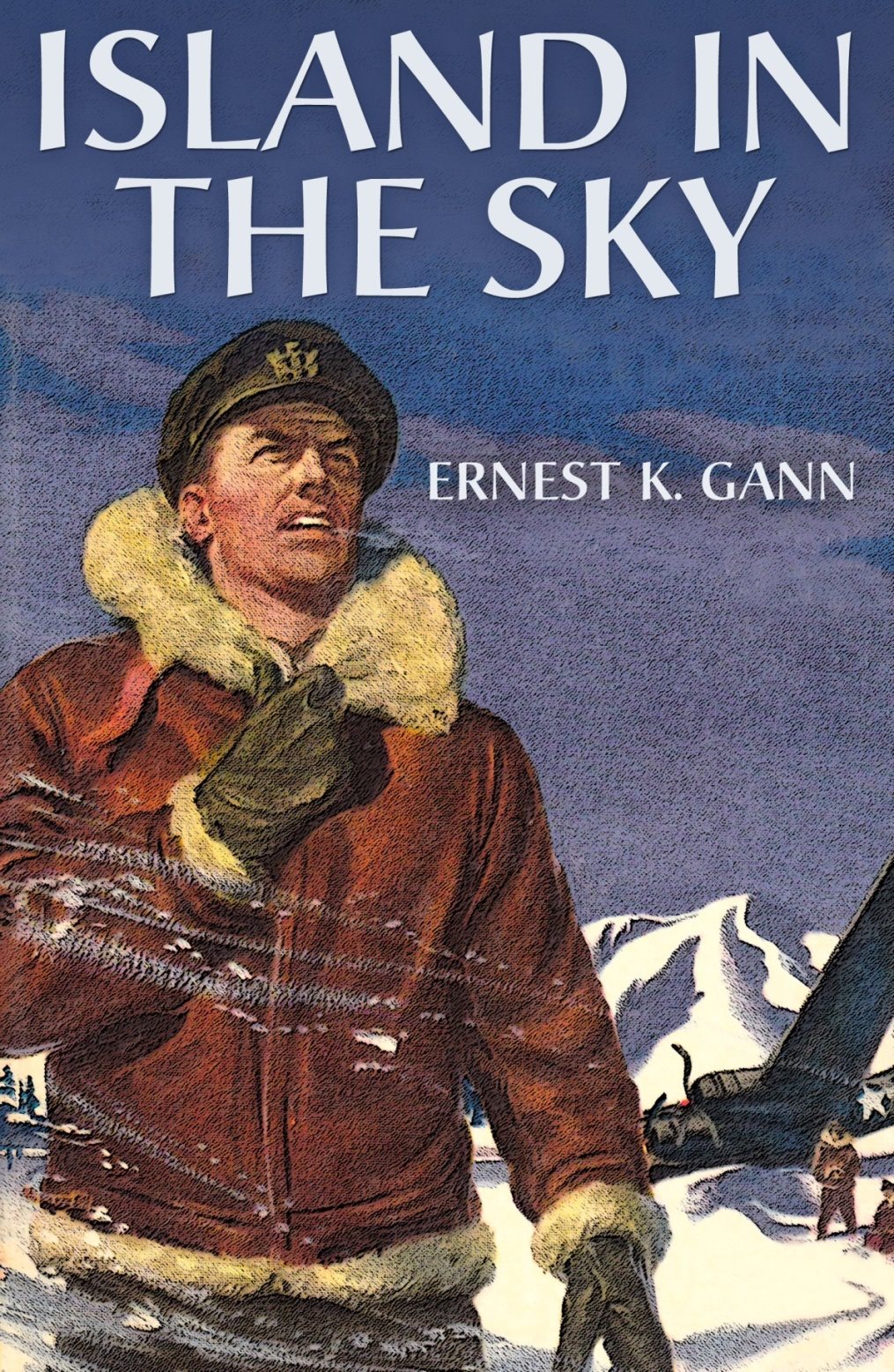

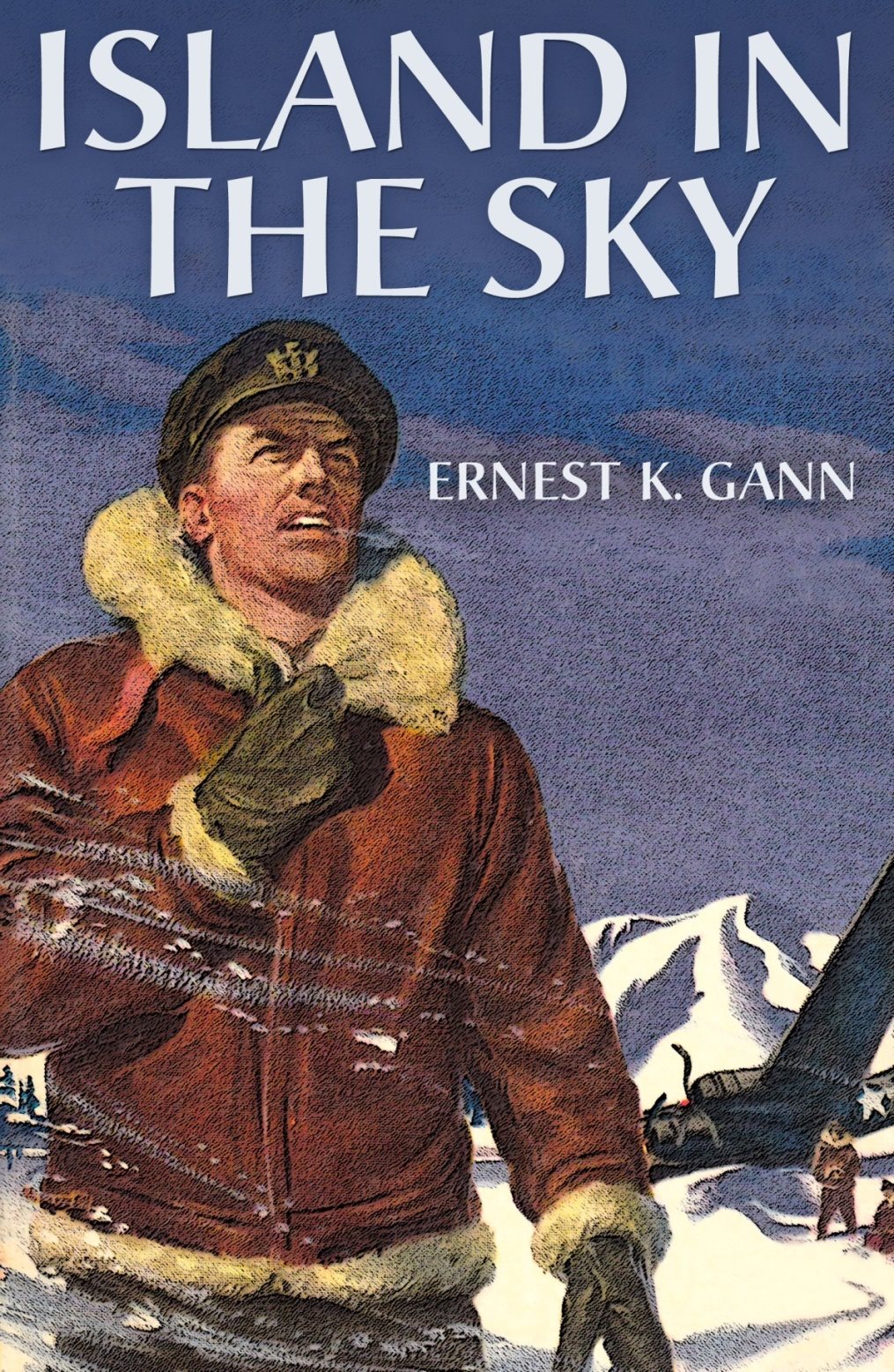

ISLAND IN THE SKY

ERNEST K. GANN

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

DEDICATION

TO TOBY HUNT

and all his kind.

Thou born to match the gale (thou art all wings),

To cope with heaven and earth and sea and hurricane,

Thou ship of air that never furlst thy sails,

Days, even weeks untired and onward, through spaces, realms gyrating,

At dusk that lookd on Senegal, at morn America,

That sportst amid the lightning-flash and thunder-cloud,

In them, in thy experiences, hadst thou my soul,

What joys! what joys were thine!

Walt Whitman To the Man-of-War Bird

Foreword

This is not a war book. It could have been written at any time since man took to the air seriously. This is a story about professional pilots and their special, guarded worldtheir island in the sky.

Before take-off, a professional pilot is keen, anxious, but lest someone read his true feelings, he is elaborately casual. The reason for this is that he is about to enter a new though familiar world. The process of entrance begins a short time before he leaves the ground and is completed the instant he is in the air. From that moment on, not only his body but his spirit and personality exist in a separate world known only to himself and his comrades.

As the years go by, he returns to this invisible world rather than to earth for peace and solace. There also he finds a profound enchantment, although he can seldom describe it. He can discuss it with others of his kind, and because they too know and feel its power they understand. But his attempts to communicate his feelings to his wife or other earthly confidants invariably end in failure.

Flying is hypnotic and all pilots are willing victims to the spell. Their world is like a magic island in which the factors of life and death assume their proper values. Thinking becomes clear because there are no earthly foibles or embellishments to confuse it. Professional pilots are, of necessity, uncomplicated, simple men. Their thinking must remain straightforward, or they dieviolently.

The men in this book are fictitious characters but their counterparts can be found in cockpits all over the world. Now they are flying a war. Tomorrow they will be flying a peace, for, regardless of the worlds condition, flying is their life.

Like the men in this book, a large number of professional airline pilots were attached to the Army Air Transport Command soon after the war began. They were of the Army but not in it. Flying alongside regular Army pilots, they continued to wear their usual airline uniforms when conditions permitted, which was seldom. Extremes of cold and heat, the dirt and rigors of far-flung operations, reduced them frequently to an identifying cap. The rest was more often a plaid shirt and heavy flying jacket, or shorts and mosquito boots, as the case might be.

The story of the Corsair and its occupants is based upon a true incident. The writer selected this story because he knew it bestthere are hundreds of other stories, some of them even more heroic, that speak of professional flying with perhaps more eloquence than this one. But no matter what story might be selected, or wherever on earth or in the air it might take place, the men involved would be much the same as Dooley and Stannish, Stutz and Willie Moon, and all the others.

E. K. G.

Old Greenwich, Conn.

1944

I

Dooley rubbed the gray stubble on his chin and stared into the evening. His heavy, sharp-cut face, Chinese red from the glow behind the overcast, made no secret of the disgust that filled his being.

I dont like, he mumbled in a leathery voice, the look of that there God damned cloud bank. Dooley always referred to things as that thereit pleased him immensely. It was an exact impression, something you could depend upon, something everyone in Dooleys vast experience had always been able to understand. He looked down 10,000 feet to the placid waters of Davis Strait. For a moment, the deep-cut lines about his mouth ceased to look like spokes around a wagon wheel. I dont like the look of it, he repeated to the world aloft in general, and then his attention returned to the cloud bank straight ahead. His eyes shifted and sought out the temperature gauge on the crowded instrument panel. The narrow pointer on the needle indicated precisely 20 degrees above zero.

Dooley lolled back in his seat and alternately rubbed his miserably chapped lips and the shock of gray hair that stood defiantly forward from the top of his head. He was tired. His eyes burned and his legs ached. His stomach, a recent host to a quantity of canned meat, felt as if it belonged to some other person. His tongue was dry. He placed an oxygen mask over his face for a moment, breathed deeply, and stared again at the cloud bank ahead. His lungs temporarily satisfied, he placed the mask carefully upon his knee and spoke to the young man at his side.

We are going to pick up some ice. He said it thoughtfully and very quietly. He seemed not to care. There was no twinkle in his blue eyes. Dooley had to thinkand think swiftly too, as swiftly as his passage through the upper atmosphere. He had to balance things, many things, one against the other. He had to work into nice juxtaposition a series of related facts that were constantly at odds with each other. In addition, they were facts that grew and changed with rapidity. Failure on Dooleys part to compromise with them would result in disaster.

Most of his preliminary thinking was automatic, based on long-established conditions. He was the captain of a four-engined transport airplane, presently somewhere between Greenland and North America. The logistics of modern warfare had brought Dooley to this forsaken portion of the sky. The Army Air Transport Command had provided the airplane, which someone had named the Corsair . The name was prominently lettered in yellow paint along its nose. A commercial airline had provided Dooley and his crew. It was a satisfactory arrangement for everyone concerned, including Dooley, whose forty-three years would otherwise have bound him to an Army desk. Now he was proceeding toward the Labrador Coast at an estimated speed of 200 miles per hour. Beneath him, far below in the twilight vastness, were numerous icebergs, strangely linked together by vagrant wisps of sea mist. Above his head, the plexiglass window revealed the Arctic evening sky. Just ahead, a scant few feet, the instrument panel offered assorted information on the airspeed, altitude, course, engine temperatures, manifold pressures, and revolutions per minute. They were pleasantly old, familiar, hard factseasy to comprehend and easy to observe. Dooleys twenty years of flying had taught him over and over again that he must not be content with them alone.

Next page