Acknowledgments

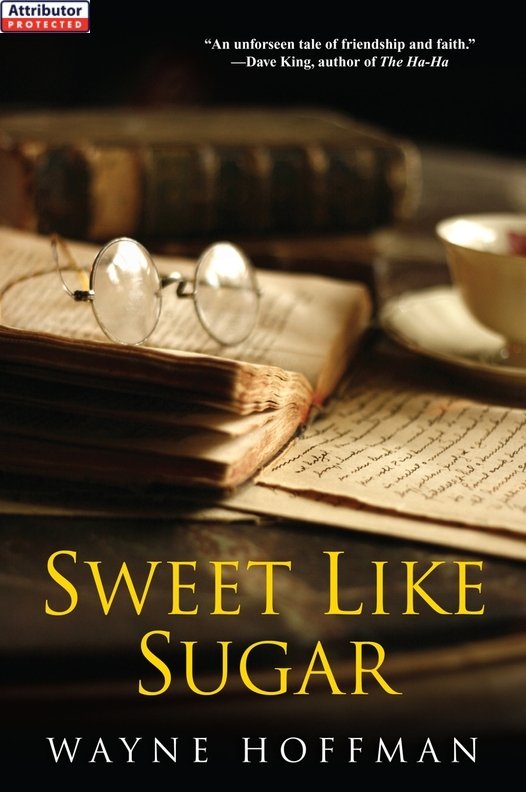

First and foremost, thanks to my editor, John Scognamiglio, and my agent, Mitchell Waters, for getting this book published, and for all their guidance along the way.

I never could have finished the project without the support and helpful advice of Carolyn Hessel, Alana Newhouse, Don Weise, and Andrew Corbin.

Several people provided me with the physical space I needed to write: Stacey Hoffman and Victor Ozols; John Nazarian and Robert Reader; and Sarah Thompson and Diane Stafford at Poor Richards Landing. My colleagues at the Forward and Nextbook Inc. allowed me the time I needed to write, which is no less important. And my friends in the Catskills helped preserve my sanity, such as it is, amid all the mishegos of writing and revising: David Nellis (and Pearl); Neil Greenberg and Frank Mullaney; John Murphy and Hal Moskowitz; and the entire Greynolds family. I couldnt have done it without all of you.

There are also, unfortunately, people who didnt live to see this books completion. Allan Berube and Eric Rofesmy beloved mentors and friends and much more, two gorgeous and generous and brilliant menwere both taken too suddenly and too soon. Jim Merritt also died after a long illness, but not before his difficult final months inspired a large chunk of this story. And my remarkable great-aunt, Irene Wolfe, passed away in 2009, but she read an early draft of the novel, so she knew that her name and a piece of her spirit would endure.

My eternal gratitude to my parents, Marty and Susan Hoffman, for being much more wonderful and supportive than Benji Steiners parents. And to my partner, Mark Sullivan, for his love, wisdom, honesty and, above all, patience.

Please turn the page for a special Q&A with Wayne Hoffman!

How did this story come to you?

One day several years ago, when I was working as managing editor at the Forward, an English-language Jewish newspaper, an editor from the Forverts our sister newspaper, published in Yiddish, with whom we shared a newsroomcame in and asked if one of his employees could rest on my couch. I didnt know this employee, didnt know his name, and didnt even know if he spoke English. But he was very ill and clearly needed to lie down and my office had the only couch in the newsroom, so I said yes. I looked over at this bearded, observant man, who was probably eighty years old, in poor health, as he slept. And I wondered who this man was, what the two of us could possibly have in common, how a conversation might go between us. And that turned into the opening scene of Sweet Like Sugar . Ive spent many years thinking about being gay and being Jewish, and how those two identities intersect or complement each other or come into conflict, so it was only natural that as I continued thinking about what a conversation with this man on my couch might sound like, these are the subjects that became the core of the story.

Is this story based on true events?

Although there are elements in the story that are based on things that happened to me, or to people I know, the story is fiction. However, the larger issues that underpin the storyhow people are brought together by fate, how religion unites and divides us, how communities can welcome or exclude people, how personal connections can help us get past our deep-seated prejudicesare true in a broad sense, if not a particularly personal one.

Are the characters based on real people?

The only character whos based specifically on a real person is Irene; I named her after my great-aunt, who died shortly after I finished writing the book. Aunt Irene had a keen sense for cutting through the bull and getting to what was really important and she had a strong belief in fate and forces beyond our control. She was never in the situations that I describe in this book, but when I was writing Irenes scenes, I had my great-aunt in mind the whole time, trying to figure out how shed react if she were in her namesakes place. Theres also a tiny piece of my maternal grandfather in Benjis grandfather: He died when I was six years old, so, like Benji, I only remember him from my early childhood. In fact, like Benji, one of my strongest memories of my grandfather was of him leading a Passover seder while my grandmother nagged him from across the table. Most of the other characters are not based on specific individuals. My own parents are much more fun to be around than Benjis, I am much closer to my sister than Benji is to his, and unlike Benji, I have a brotherwho, ironically enough, is a Conservative rabbi, one far more broad-minded than this books Rabbi Adler. I dont have a roommate like Michelle, but I do have women in my life who have played similar roles; thats true for lots of gay men.

Much of the book takes place in suburban Washington, D.C. How do you know this area?

Even though Ive spent most of my adult life in New York City, I know this area firsthand. I grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland, very close to where the book is setthats where I went to Hebrew school, attended synagogue, learned Israeli dance, worked at the JCC, and spent summers at a Jewish camp. My parents still live there, so I visit frequently. I am well acquainted with how the Jewish community operates there and how the gay community does, too. Parts of the book are set decades ago in Jersey City, which is where my mother grew up in an Orthodox household, so I know that area during that period, as well, secondhand.

Has your spiritual journey been different from Benjis?

I grew up Conservative, like Benji. And I, too, felt alienated from a young age, despite feeling a certain sense of connection to individual parts of that tradition. But I havent wrestled in the same way; I found a place in the Jewish community where I feel comfortable many years ago.

A READING GROUP GUIDE

SWEET LIKE SUGAR

Wayne Hoffman

ABOUT THIS GUIDE

The suggested questions are included

to enhance your groups reading

of Wayne Hoffmans Sweet Like Sugar .

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Even though Benji feels alienated from his Jewishness, Jewish holidays play a large part in his story: His memories of Passover appear in the first and last chapters, and in the middle, he goes to synagogue for Rosh Hashanah, attends a Hanukkah party, bakes hamantashen for Purim, and flashes back to Shabbat services from his childhood. What role do holidays play in maintaining Jewish identityeven for people who feel disconnected from traditional Judaism?

How much of the story is unique to Jews? Could a similar story play out with non-Jewish characters? How might it be different?

As Rabbi Zuckerman and Benji get to know each other, there are several opportunities for Benji to tell the rabbi that he is gay or for the rabbi to ask. Why doesnt it happen sooner? Do you think it was a mistake for Benji to bring it up how and when he did? Did the rabbi react inappropriately? How might both men have handled it differently?

Irene implies that the rabbi sent Benji to Florida to meet herthat their meeting was not an accident or even something the rabbi feared. Do you agree? Why might the rabbi have wanted Benji and Irene to meet?

If Irene hadnt played intermediary, do you think Benji and the rabbi could ever have repaired their relationship? If Benji hadnt intervened, do you think the rabbi and Irene would ever have reconnected?