Dedicated to the memory of my mum, Barbara, my dad, Joseph, my cousin Lee, friends Natalie and Neil, and all those who are gone long before their time.

CONTENTS

There are a great many people who have contributed to the book in one way or another. I am extremely grateful to them all. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but I would particularly like to thank the following.

All the survivors, relatives and people who participated in the rescue and care in the aftermath, and who contributed to this book.

Pascale Bernard for French translations, and Christine Geyer for German translations; Inge Desmedt for being a better Belgian detective than Hercule Poirot ever could be (sorry for the chair); Jackie Badger and Paul Wightman for turning a blind eye when I should have been working; Nicola Dobson for proofreading; Eamonn Farrell for saving my laptop from the bin; Rebecca Sawbridge, Janet Johnson and Peter Southcombe for filling in the blanks; Patrick Mylon for his encouragement; Gary and Tracy Sexty, Steve and Jan Booth, Caroline Mylon, Mike Peach, Chris Mooney, Eric Sauder, Brian Hawley, Lynne Hawkins, Paul Rogers and Katie Beresford for their support and enthusiasm; and to Mick Goddard for his day-to-day support, reading, driving me around and putting up with my many tantrums.

Finally, I would like to thank Chrissy McMorris and Amy Rigg at The History Press for having enough faith in me to make this book a reality.

Players

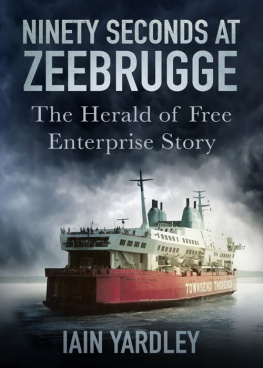

Former artillery officer Captain Stuart Townsend was fed up with being charged exorbitant fees to transport his car across the English Channel by steam packet boats. He decided to start his own shipping line and, after talks with the Automobile Association (AA) and Royal Automobile Club (RAC), Townsend Brothers Ferries Ltd was in business by 1928. The coal ship Artificer, capacity fifteen cars and twelve passengers, was chartered, and a shipping link between Dover and Calais was established in June of that year. The service became so popular that it became permanent in 1929. Owing to the demand, the Artificer was replaced by the Royal Firth, followed by a former minesweeper, renamed the Forde, in April 1930.

The Forde could carry thirty cars and 168 passengers. For six years, cars were lifted by mobile ramp onto the Forde, until a strike by Calais dockers and crane operators in 1936. For the duration of the strike, the Fordes stern rails were removed and cars driven onto the ship via makeshift platforms. Although strictly a one-off temporary arrangement, it undoubtedly gave Townsend the idea for roll-on/roll-off (RORO) ferries for the future. It wasnt until fifteen years later, in 1951, that drivers were allowed to drive their own cars onto a ferry, when the Forde was replaced by a converted frigate.

The first RORO berths in Dover and Calais were installed in 1959. Then, in 1962 the frigate was superseded with the introduction of Townsends first purpose-built car ferry, Free Enterprise I, on the DoverCalais route; so named because Townsend were celebrating their private sector status and breaking away from a state-run service.

The second purpose-built ferry, the Free Enterprise II, became the first British registered, seagoing, drive-through ferry with bow and stern doors, upon its introduction in 1965. A year later, Free Enterprise III was introduced onto Townsends second route, DoverZeebrugge.

Frank Bustard was an apprentice and friend of fellow Liverpudlian, J. Bruce Ismay, who was chairman of the White Star Line (WSL). Ismay survived the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. Bustard was awarded an OBE for services during the First World War, after which he became the passenger traffic manager for the WSL. In 1934 the same year that the WSL merged with Cunard Bustard set up the Atlantic Steam Navigation Company Ltd.

Bustard wanted to set up a line offering a moderately priced transatlantic passenger service between Europe and the United States. He was unsuccessful in acquiring surplus Red Funnel Line vessels and, despite approaching Vickers Armstrong for two new ships, the government was reluctant to see a new company operating in competition to Cunard White Star. The Bank of England refused him a loan.

The looming Second World War put paid to his intentions Bustard was called up to the army reserve. During the war, he was present at the trials of landing craft loading and unloading vehicles on the beach at New Brighton, and after the war, in 1946, Bustard concentrated on vehicle-carrying ferries to operate on the short sea routes across the North Sea.

Atlantic used chartered converted tank carriers, 3519, 3534 and 3512, to start a service from Tilbury to Hamburg, predominantly for freight. Twelve years after being founded, Atlantic sailed its maiden voyage in 1946, using the converted 3519, now renamed Empire Baltic. Two years later, the worlds first commercial RORO service was established by Atlantic when the Empire Doric sailed between Preston, Lancashire and Larne.

A service to Rotterdam was established in 1960, also mainly for freight, and this lasted for six years. Atlantics FelixstoweRotterdam services, developed in 1964, and FelixstoweAntwerp service in 1965, had led to the demise of the Tilbury operations. All services from Tilbury ended in 1968 as they became uneconomical. In 1968, Atlantic became part of the National Freight Corporation. The seven ships which had been its fleet all gave a nod to ships of the White Star Line.

Southampton based Otto Thoresen Shipping Company was set up in 1964 by a group of Norwegian investors. The Norwegian registered company operated RORO Services between Southampton and Cherbourg and Southampton and Le Havre. Thoresen Car Ferries, a wholly British-owned subsidiary company, was formed as an agent for these RORO services in the UK. Services began that same year with the ferries Viking I and Viking II. A year later these two ferries were joined by Viking III and Viking IV. The ferries were so named to reflect the companys Scandinavian origins.

These three major players eventually became the same group in 1971 after a series of acquisitions by George Nott Industries, formerly Monument Securities, incorporated in 1935. Monument acquired all the capital of Townsend in 1959. It then acquired Otto Thoresen in 1968, liquidating the company but retaining its subsidiary Thoresen Car Ferries. With the merging of the two major ferry companies, George Nott changed its name to European Ferries Ltd (EFL). With the takeovers of the Stanhope Steamship Company Ltd, Monarch Steamship Company Ltd and Atlantic in 1971, the company used the name Townsend Thoresen to market their combined ferry services.

There were two types of traffic carried by EFL freight and tourist. Freight comprised commercial road haulage vehicles and the importing and exporting of new cars. The vessels assigned to carry predominantly freight were mostly multi-purpose RORO ferries or purpose-built ferries. Tourist traffic was classified as foot passengers, cyclists and accompanied vehicle traffic, including the drivers and passengers of cars, coaches and caravans. Tourist traffic also included both pleasure and business travellers. These journeys were mostly undertaken by multi-purpose RORO or passenger and vehicle ferries.

The decline of cross-Channel overall profits in 1980 was blamed on the fall in freight due to the recession, competition and a blockade by French fishermen. EFL, on the other hand, enjoyed a 50 per cent rise in tourist traffic in 1980 compared to the previous year, with the Dover routes accounting for almost all shipping profits that year.

In the late 1970s the competition for cross-Channel passenger and cargo traffic in the Dover Straits was fierce. Most of the British short sea routes were still under the control of Sealink, the state-owned railway fleet. Freight completion had become crucial as firstly railway-owned hovercraft had grabbed a large share of the passenger market. Although a joint UKFrench Government-backed scheme to build a channel tunnel between the two countries had been cancelled in January 1975, it was still anticipated that a tunnel would eventually be built, which would take an even bigger part of the passenger market. In answer to this, Sealink had planned to monopolise the market by building new ferries with double-decker vehicle decks, primarily for the DoverCalais route, the shortest crossing between the United Kingdom and the European continent, and also the most profitable. By operating vehicles on one ferry at a time, it would ensure a high freight capacity, which was vital for business. When it learned of Sealinks plans, the Townsend Thoresen response was immediate.

Next page