Afterword

My first memory of Tom Davis is at the Tanglewood Music Festival, summer 2006. We were there to celebrate Jon McIntires sixty-fifth birthday. I had given Jon, a former manager of the Grateful Dead, a dozen tickets for his chosen friends to celebrate his birthday at the premier performance of an avant-garde composer. Tom Davis, Jons friend, wouldnt accept a ticket. He would not commit to coming. If he could make it, hed buy his own ticket. Tom Davis bounded up alone to the front gate at Tanglewood, full of energy, dancing rather than walking, tall and robust, long stylish hair and a beard. His voice was clear and sharp with a melodic timbre, fully embodied, and I heard him above the others.

Tom remembers our first meeting differently. He claims we met at the home of our publisher, Paul Cohen, and when a downpour suddenly burst from the sky, took refuge in a sheltered gazebo. For hours, with nothing to do, stuck in a small space, only three or four of us, we bonded. Toms story is much more poetic, has a beginning, a middle, and an end, connects us to the futurea great sketch, even if it stretches the truth. So like Tom.

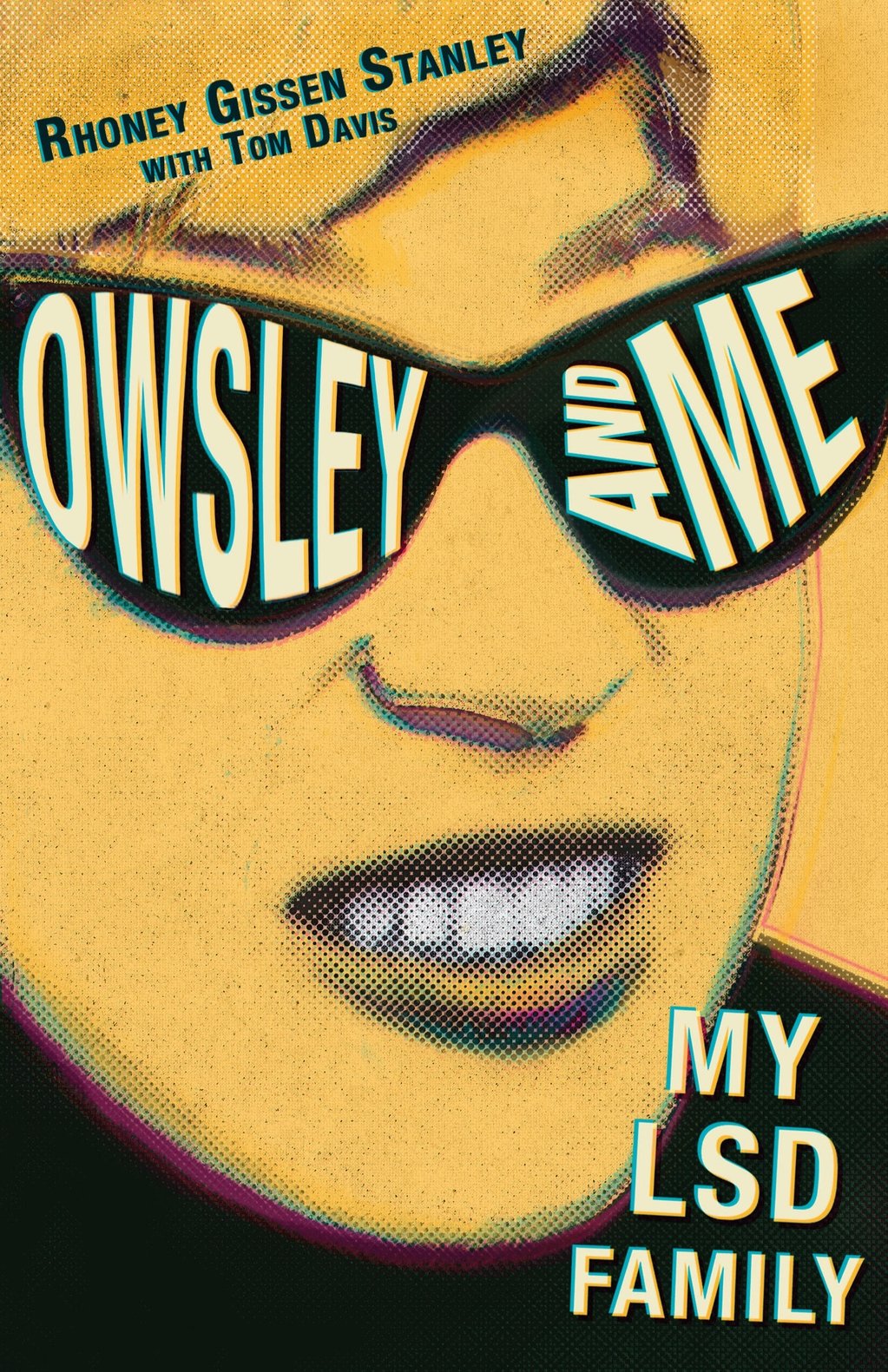

We attended exhibits of rocknroll posters; we went to shows. Anything to do with Grateful Dead music we shared. Our conversation never flagged. He was finishing his memoir, Thirty-Nine Years of Short-Term Memory Loss , and I was at my chronic task of writing Owsley and Me . I told him that when Jerry Garcia died in 1995, I sent zillions ofemails to members of the Grateful Dead and to Grateful Dead family, declaring that the Grateful Dead must go on. Then I heard Garcias voice saying, if you feel that strongly, write your own story. I told him how my efforts at collaboration had failed. I felt that Garcia had brought Tom and me together. Tom did not.

When I told Owsley I had become friends with Tom Davis, he said, How dare you! He was the one who turned Garcia on to the Persian.

Awed by Toms pedigree, I ignored Bear. Tom and I exchanged writing. He had purposely written his book showing little emotion, letting the reader find the feeling, but my story was a soapy tearjerker. Tom became my editor and changed that. When the chemo he was getting for his head and neck cancer failed, he decided to be my coauthor. His health waned, but his natural brilliance at writing soared. His sharp wordsmithing, his understanding of comedy concepts and the nature of reaction, his outstanding ability at sketch design and dialogue, his dedication to the jewel of memory transformed Owsley and Me .

Rhoney Stanley

Rhoney Gissen, student days at UC Berkeley

Alvan Meyerowitz

Neti Neti: Neither This Nor That

No music was playing on the car radio as we drove onto the Mount Holyoke College campus. I cringed in the backseat, small as I was, slumped down, wishing for invisibility, embarrassed to be arriving for my freshman year at college in a big car driven by a black man in a chauffeurs hat. My mother couldnt take time from her busy schedule of luncheons to drive me to college and had sent me with my grandmothers chauffeur. We checked in at the front desk of Mary Lyon Hall, a nineteenth-century stone building covered in ivy.

My roommate was six feet tall, from Kenilworth, Illinois, the Gold Coast suburb of Chicago with country clubs where Jews were restricted from membership. Different in many ways, we both couldnt tolerate the Tuesday and Thursday morning mandatory chapel, the signing in and signing out, the dress code for dinner, the eleven oclock curfew, the bell that chimed every fifteen minutes, ringing so many hours of the day that it became a normal sounda ringing that was part of being, an accustomed anxiety.

Smoking was only allowed in designated smoking rooms, and here I found my place. I took a dare to go drinking with the girls at a town pub. I furtively left the dorm in a short skirt and high-heeled boots and joined the other girls at the bus stop. The local bar smelled like stale cigarettes, alcohol, and urine; I chain-smoked Marlboros that I bummed off the upperclassmen, laughed loudly,and raised my Black Russian in besotted camaraderie. To sneak back into the dorm, I crept through an open window and knocked over a glass vase on the windowsill. It shattered on the floor and woke up the House Mother. She shook her finger and threatened me with a hearing before the studentfaculty board.

Mount Holyoke was on the honor system, and I told the truth. The following week the House Mother called me into her office and handed me an envelope addressed to me with the Mount Holyoke seal, a picture of palm trees, mountains, and a small building, dated 1837. It quoted Psalm 144:12: Our daughters may be as cornerstones polished after the similitude of a palace. I did not open the letter in front of her and left without saying anything. In my dorm room, sitting on the narrow bed, I read the verdict of the Board. They had judged me harshly. I was put on disciplinary probation and required to see the college psychiatrist.

In an office at the infirmary, the doctor sat behind a desk wearing a white jacket, her hair in a perfect coiffure. She spoke with a stern voice: I broke the rules; I did not understand the value of tradition; I was too easily influenced; I needed to obey authority. This shrink had no respect for thinking outside the box. It was obvious I would have to transfer. I considered the University of Chicago where Robert Hutchins had instituted the Great Books program whose mission was to teach the responsibility of citizenship. But the University of California at Berkeley was the hottest hotbed of political action, and it was as far away from my family as I could get, psychiatrically.

I didnt have far to look for alternative lifestyles in Berkeley, California. Outside the administrationbuilding on Sproul Plaza, students gathered at the Fountain to exchange ideas and discuss the escalating attack on Vietnam by the Kennedy administration. The more forthright ones set up tables at Bancroft Way and Telegraph Avenue on the edge of campus and distributed leaflets denouncing war and calling the administration fascist pigs. My new roommates were Red diaper babies, the daughters of Red Communist American parents. We protested US policy on Vietnam and Cuba. We marched in black pumps with little heels and skirts with hemlines that ended below the knees and bras to keep our boobs from jiggling.

Thus began a streak of nightly meetings to plan a strategy to end the Vietnam War. If you felt the urge, you could stand in front of the group and speak your mind. I was shocked that several advocated violence. One decent guy with a Lenin T-shirt and ponytail stood up and yelled, Bullshit! We dont need guns to make change! We brought him home and his buddy tagged along. We put on a Ray Charles record and danced. Left-wing politics was very sexy.