Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2018 by Steve Willard

All rights reserved

All photographs courtesy of the San Diego Police Museum unless otherwise noted.

First published 2018

e-book edition 2018

ISBN 978.1.43966.581.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018948033

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.855.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For Julie E.M. Willard

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Credit is due to the following: the men and women of the San Diego Police Department, specifically the Detective Bureau, for their dedication, sacrifice and bravery, some of which will be narrated in the forthcoming pages; the staff, volunteers and supporters of the San Diego Police MuseumJim Arthur, Richard Bennett, Rick Carlson, Randy Eichmann, Stan Elmore, Tom Giaquinto, Ed LaValle, Andrea and Jesse Meador, Mark Mendelsohn and Pat Vinsonfor their preservation of the SDPD legacy; Carolyne Joseph for review; Neil Joseph for photography; Suzanne Russell for flow and content; and last but not least, the master, the man whose friendship has inspired my true crime writing, the worlds bestselling police author, Joseph Wambaugh.

INTRODUCTION

The thin blue line of police is the only thing standing between anarchy and chaos.

Los Angeles Police Department chief William H. Parker

Regardless of the location in which police officers serve, the times we live in have made the job of an American uniformed patrol cop perhaps the most high-profile profession in the United States. Admittedly, it takes a special person to try and an even more unique person to walk the blue line day in and day out. That said, there exists a crucial element of American law enforcement often overshadowed by their more visible counterparts; they are the plainclothes detectives of The Bureau. These skilled men and women seldom wear uniforms and rarely drive marked police cars. Their work is better suited behind the scenes, in the shadows of the thin blue line, as they piece together clues, common sense and physical evidence to solve cases and deliver justice.

Twenty-five of my thirty-three-year career has been spent in the Detective Bureau of the San Diego Police Department. So when I had the opportunity to deliver a narrative of San Diego crime, I wanted to do it from their perspective.

The cases are real. The cops are all true-life characters who once served the SDPD. Only in the cases of sexual assault have the names been changed to protect the innocent.

The information presented is derived from police reports, museum archives, newspapers and memoirs. Some creative licensing, such as dialogue, attire, mannerisms and other minor elements, was taken to provide the reader an immersive experience in what it was like to fight crime in the Roaring Twenties era of American justice.

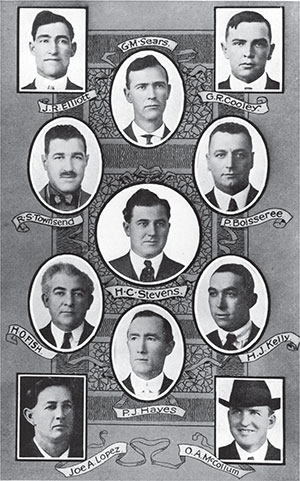

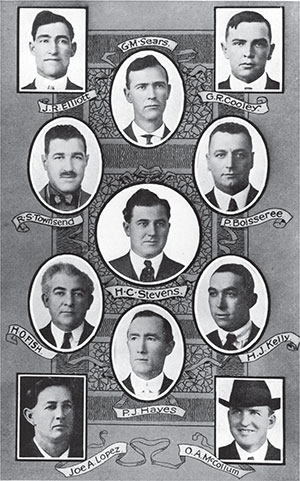

SDPDs small but efficient Detective Bureau, circa 1918.

CHAPTER 1

DEATH OF THE STINGAREE

Almost a century before the Gaslamp Quarter became San Diegos trendy tourist district of shopping, dancing and fine dining, it was filled with as much debauchery as the vice-ridden Barbary Coast of San Francisco. That is, until San Diegos most innovative police chief said, Enough.

SUNDAY MORNING, NOVEMBER 10, 1912: Plainclothes bureau men and uniformed patrolmen of the San Diego Police Department swarmed the Stingaree Districta notorious neighborhood of opium dens, brothels and saloons that served thirsty sailors in port as well as local residents drawn to sin.

Armed with rifles, warrants and a personal directive from Chief of Police Jefferson Keno Wilson, the cops began kicking down the doors of every known brothel, some of which had been open as far back as 1885. The women were hauled to the curb in shackles to be transported to police headquarters. The horse-drawn prisoner wagon had a ten-passenger limit, forcing many officers to walk the women to the police station. Newspapers later recalled, If one lagged behind or threatened to bolt, an officer would blow a whistle and shake his billy club at the offender. There was not a single case of resistance or protest, wrote the San Diego Union. The women laughed their way to the station good naturedly. They treated the round-up as a joke.

By the end of the raid, SDPD had arrested 138 prostitutes, at least half under age seventeen. Not a single John was arrested. Prostitution in those days was strictly a female crime.

For the next seven hours, Chief Wilson, Deputy City Attorney D.F. Glidden and an immigration officer interviewed the women one at a time in the chief s office. A dossier was created for each arrestee, including their names, dates of birth and where they were from. The most important question was would they reform or leave San Diego the next day?

Many of the women gave their last name as Doe. The younger ones claimed they were born in 1888 so they wouldnt be arrested as juveniles, though about 70 percent were between thirteen and seventeen years old. The chief estimated at least nine-tenths of the women had come to San Diego within the last six months due to L.A. closing its red-light district.

Telling the women to leave town proved to be a temporary solution. If the problem was going to be eradicated, the opium dens and brothels needed to be closed forever.

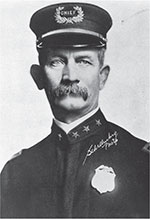

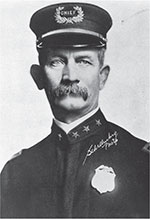

Keno Wilson closed the Stingaree and then diversified the SDPD in an era when society didnt want it. His integrity and innovation eventually cost him his job.

1915: AS PREDICTED, THE 1912 Stingaree sweep was a temporary fix to a much larger, more complicated issue. For the women who refused to leave town, the chief watched the criminal cases fall away when local power brokers, many of whom either frequented the Stingaree brothels or owned a stake in them, began leaning on local prosecutors to drop the charges.

Something else needed to be done, and Keno Wilson had the guts to do it.

In 1909, Wilson had just taken office as chief when he made a bold decision: he hired Frank McCarter as a special patrolman. Today, the appointment of a black officer wouldnt raise an eyebrow. In 1909, it was huge news and not welcomed by a large swatch of the local population.

Several years later, Wilson again made waves with how he responded to complaints about signs in some local restaurants. Leaders in the black community were upset with signs banning them from some of the finer eating establishments. Keenly aware of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, the crafty chief instead enforced an obscure ordinance related to the size of signs and how they were placed on the building. While not as dramatic as ripping down the offensive signage, the end result was the same: the signs were taken down.

Next page