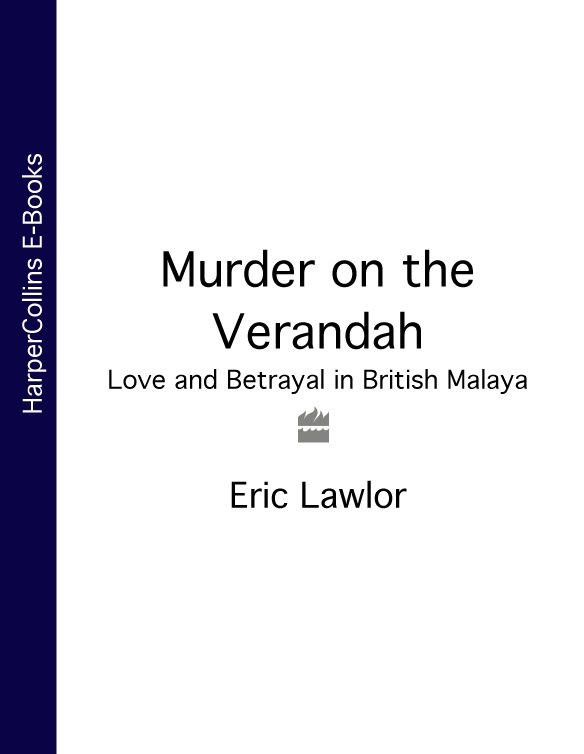

It was my great good luck at the beginning of this project to be put in touch with Henry Barlow. Barlow, who lives in Kuala Lumpur and whose family has been associated with the Malay Peninsula for much of this century, has amassed a great wealth of information about British Malaya which, over several months, he was gracious enough to share with me. It was he, too, who introduced me to John Gullick, Englands leading Malaya scholar, whose help was not just enormous, but crucial as well. This generous man paid me the great compliment of treating my book as if it were one he was writing himself.

I must thank as well John G. Butcher, whose landmark study The British in Malaya 1880-1941 I drew on again and again, and who alerted me to the existence of a letter penned by William Stewards brother-in-law in Malaysias national archives. Tissa Perera, of the Incorporated Society of Planters also provided valuable assistance. His allowing me access to back issues of The Planter was especially useful and yielded material that might otherwise have been unavailable to me.

Others helped in significant ways as well: Pennie Redmile in Montreal, Nicola Liddiard in London and Ian Green in Guildford assisted in the search for William and Ethel; Sally Lee found a home for me in Kuala Lumpur; Eloise Rochelle, more computer literate than I, negotiated the Internet on my behalf; Dilys Yap of Badan Warisan Malaysia directed me to the Victoria Institution; Woo Kum Wah conducted me around the Selangor Club; and Terry Barringer, who also has charge of materials in the Royal Commonwealth Society collection at Cambridge University, helped in the choosing of photographs.

To finish, I must extend my gratitude to Gillon Aitken, my remarkable agent: had he not intervened when he did, this book would not exist; and also to the people at HarperCollins: the ever-gracious Annie Robertson, my unflappable editor Rebecca Lloyd and, most especially, Michael Fishwick, the publishing director, whose good humour and patience made writing this book a very happy experience.

Coelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt

The sky, but not the heart, they change who speed across the sea

FROM H ORACE , T RANSLATED BY H. D ARNLEY N AYLOR

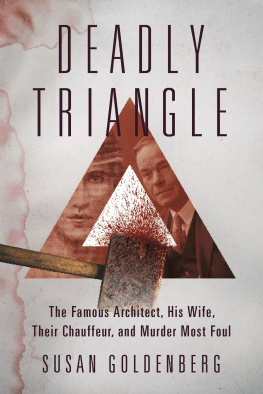

On 23 April 1911, Ethel Proudlock, as was her custom on Sundays, attended Evensong at St Marys Church in Kuala Lumpur. She was well known at St Marys. From time to time she helped with jumble sales and had recently joined the choir. After the service, a friend invited Ethel to join her for dinner, but she declined. Her husband was going out for the evening, she said; it would give her a chance to write some letters. Then, after checking that the hymnals were in order, she walked home and killed her lover.

Claiming self-defence, she told police that William Steward had turned up unexpectedly that evening and tried to rape her. None of this was true. Steward was there because Mrs Proudlock had invited him, and he died shot five times at point-blank range after telling her he was ending their affair.

The Proudlock case, the basis of The Letter, the most famous of Somerset Maughams short stories, galvanized British Malaya. Some Britons insisted she was innocent, but the evidence against her was overwhelming and, after a trial lasting nearly a week, Ethel Proudlock was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to die. Preparations to hang her were well advanced when the Sultan of Selangor intervened. Citing her youth and the fact that she was a mother, he granted her a pardon. But the trial had unhinged her. Ordered to leave Malaya, Mrs Proudlock, with her husband and three-year-old daughter, returned to England a virtual invalid.

Until she was arrested, there was little to distinguish Ethel Proudlock from other members of the British community. Like them she was middle-class, seemed perfectly conventional and, to all appearances, was happily married. Ethel Proudlock fitted in, her defenders said. She couldnt possibly be a killer; she was one of them. But the fact remained: Ethel Proudlock had killed. Why?

Some suggested that she might be mad. Mrs Proudlock was dangerously unstable, they said; a person whose violent mood-swings had long been the subject of gossip. Others blamed vindictiveness. Ethel made a bad enemy, according to this view. Offend her even slightly, and she was implacable. A third group this one made up of Kuala Lumpurs Chinese and Malays attributed the killing to arrogance. Ethel was a member of Malays ruling caste and, as such, thought she could do as she pleased. When she pulled the trigger that night, she was exercising the prerogatives she believed were hers by virtue of her station.

There is a fourth, more plausible, possibility. When Ethel married, she was a girl of just nineteen whose sheltered background can hardly have prepared her for the pressures and artificialities of colonial life. Might it be the case that those pressures proved too much for her? Answering that question necessarily raises others. What were the British in Malaya really like? How did they comport themselves? Did they enjoy the country? What did they see as their role there? Were they, as some have claimed, a force for good? Or were they opportunists?

Colonial Malaya, often described as Cheltenham on the equator, has not lacked for study. Its politics have come in for much attention, as have its economics, but about the British themselves we know surprisingly little. The oversight is regrettable. While the society they created was neither as complex as Indias or nearly as grand, it was no less intriguing. No one clung more tenaciously to their ancestral ways than did the British in Malaya; and no one was more convinced of their natural superiority. The institutions they created in that country may well have been unique.

Complicating any effort to take the measure of these people is a controversy set in motion some seventy years ago by Somerset Maugham. Maugham is as much associated with Malaya as Kipling is with the British Raj but, unlike Kipling, who was born in India and spent much of his life there, Maugham visited Malaya only twice: for six months in 1921 and a further four in 192526. Yet out of that short acquaintance came his most enduring achievement a group of short stories bringing Malaya so vividly to life that people named it Maugham Country.

Maughams portrait of Malayas colonials is less than flattering. The planters and officials in his stories are dull and mediocre, eaten up with envy of one another and devoured by spite. Their wives are even worse: The women, poor things, were obsessed by petty rivalries. They made a circle that was more provincial than any in the smallest town in England They were sheep.

Cyril Connolly said of Maugham that he had done something never before achieved: He tells us exactly what the British in the Far East are like. The British in Malaya did not agree. They said theyd been betrayed. They had taken Maugham into their homes, introduced him to their friends, made him a guest at their clubs. And for this, he had defamed them. Who are we to believe? This book is an attempt to answer that question.

One thing can be said at the outset: the British changed when they went overseas a change that was commented on again and again. As one visitor put it: Two Englishmen, one here and one at home, might easily be men of different race, language, and religion so different is their outlook and behaviour.

In so far as it is useful, I have tried to let these people speak for themselves. This is their story after all and it seems only right that I let them help me tell it. I also draw much on the