Published by Inhabit Media Inc.

www.inhabitmedia.com

Inhabit Media Inc. (Iqaluit) P.O. Box 11125, Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 1H0

(Toronto) 146A Orchard View Blvd., Toronto, Ontario, M4R 1C3

Design and layout copyright 2015 by Inhabit Media Inc.

Text copyright 2015 by Kenn Harper

Images copyright as indicated

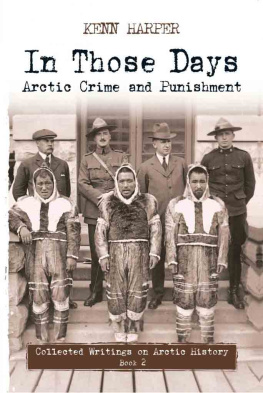

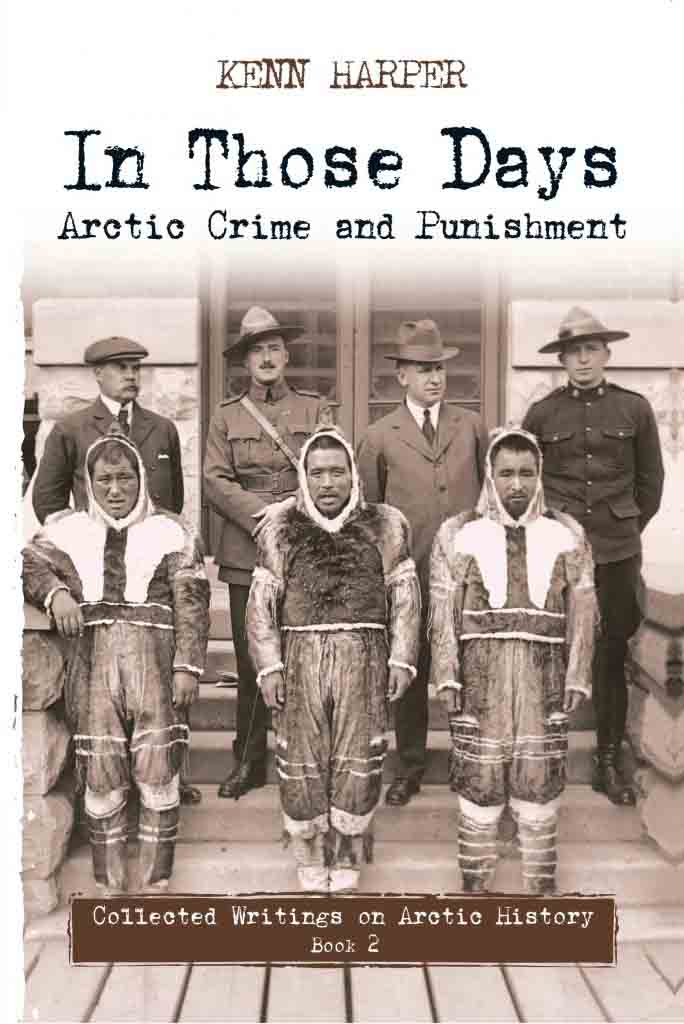

Cover image: Two Copper Inuit prisoners, RNWMP, interpreters, witness, and judicial officials, at murder trial, Edmonton, August 1917. Library and Archives Canada / MIKAN 4097301

Cover design by Inhabit Media Inc.

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrievable system, without written consent of the publisher, is an infringement of copyright law.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Department of Canadian Heritage Canada Book Fund.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program.

ISBN 9781772272789 (ePub.)

Table of Contents

Collected Writings

Introduction

T his is the second volume to emanate from a series of weekly articles that I wrote over a tenyear period under the title Taissumani for the Northern newspaper Nunatsiaq News. This volume presents stories of crime and punishment in the North. They are stories of real events, involving Inuit and Qallunaat (white people), and the interactions between these two very different cultures. All of the episodes can be documented from the historical record. For some, there is an extensive paper trail; for others, it is scanty. Inuit maintain some of these stories as part of their vibrant oral histories. We need to know these stories for a better understanding of the North today, and the events that made it what it is. They enhance our understanding of Northern people and contribute to our evolving appreciation of our shared history.

I have lived in the Arctic for almost fifty years. My career has been varied; Ive been a teacher, businessman, consultant, and municipal affairs officer. I moved to the Arctic as a young man, and worked for many years in small communities in Qikiqtaaluk (then Baffin) Regionone village had a population of only thirtyfour. I also lived for two years in Qaanaaq, a community of five hundred in the remotest part of northern Greenland. Wherever I went, and whatever the job, I immersed myself in Inuktitut, the language of Inuit.

In those wonderful days before television became a staple of Northern life, I visited the elders of the communities. I listened to their stories, talked with them, and heard their perspectives on a way of life that was quickly passing.

I was also a voracious reader on all subjects Northern, and learned the standard histories of the Arctic from the usual sources. But I also sought out the lesserknown books and articles that informed me about Northern people and their stories. In the process I became an avid book collector and writer.

The stories collected in this volume all originally appeared in my column, Taissumani, which I write for Nunatsiaq News. Taissumani means long ago in Inuktitut. In colloquial English it might be glossed as in those days, which is the title of this series. The columns appear online as well as in the print edition of the paper. It came as a surprise to me to learn that I have an international readership, which I know because of the comments that readers send me. I say it was a surprise because I initially thought of the columns as being stories for Northerners. No one was writing popular history for a Northern audience, be it native or nonnative. I had decided that I would write history that would appeal to, and inform, Northern people. Because of where I have lived and learned, and my knowledge of Inuktitut, these stories would usually (but not always) be about the Inuit North. The fact that readers elsewhere in the world show an interest in these stories is not only personally gratifying to me, but should be satisfying to Northerners as wellthe world is interested in the Arctic.

I began writing the series in January 2005. Originally the articles were datelined. I picked an event in the past that could be accurately dated, and wrote a column about it on the anniversary of that date. But I eventually found that formula unduly restrictive. Since shaking off the shackles of the dateline, I have simply written about an event, person, or place that relates to Arctic history. Most deal with northern Canada, but some are set in Alaska, Greenland, or the European North. My definition of the Arctic is looseit is meant to include, in most of the geographical scope of the articles, the areas where Inuit live, and so this includes the subArctic. Sometimes I stray a little even from those boundaries. I dont like restrictions, and Nunatsiaq News has given me free rein to write about what I think will interest its readers.

The stories are presented here substantially as they originally appeared in Taissumani, with the following cautions: Some stories that were presented in two or more parts in the original have been presented here as single stories. For some, the titles have been changed. There have been minimal changes and occasional corrections to the text. I have occasionally changed punctuation in direct quotations, if changing it to a more modern and expected style results in greater clarity.

The chapters have been organized generally in chronological order. They are meant to be read independently.

Qujannamik.

Kenn Harper

Iqaluit, Nunavut

A Note on Word Choice

I nuk is a singular noun. It means, in a general sense, a person. In a specific sense, it also means one person of the group we know as Inuit, the people referred to historically as Eskimos. The plural form is Inuit.

A convention, which I follow, is developing that Inuit is the adjectival form, whether the modified noun is singular or plural; thus, an Inuit house, Inuit customs, an Inuit man, Inuit hunters.

Some stories refer to Inuit in northwestern Greenland (the Thule District). They refer to themselves in the plural as Inughuit. The singular, Inughuaq, is seldom used, Inuk being used instead. The adjectival form is Inughuit.

The language spoken by Inuit in Canada is Inuktitut, although there are some regional variations to that designation. The dialect spoken in the western Kitikmeot Region is Inuinnaqtun. That spoken in Labrador is called Inuktut. The language spoken by the Inughuit of northwestern Greenland is Inuktun.

The word Eskimo is not generally used today in Canada, although it is commonly used in Alaska. I use it if it is appropriate to do so in a historical context, and also in direct quotations. In these contexts, I also use the old (originally French) terms Esquimau (singular) and Esquimaux (plural).

I have generally used the historical spellings of Inuit names, sometimes because it is unclear what they are meant to be. The few exceptions are those where it is clear what an original misspelling was meant to convey, or where there is a large number of variant spellings.