Told with his trademark empathy, Mark Isaacs cuts through cruel politicising and empty rhetoric to show our common humanity and a story of individuals at their very best.

DEBRA ADELAIDE

As someone who was born in war and grew up in war, I know that peace cannot be achieved without the people of the land. The so-called peace projects of the superpowers have always ignored the people. Mark Isaacs book focuses on one project established by young people of Afghanistan a project where young Afghans grow ties across communities as they themselves reach toward peace in their homeland.

BEHROUZ BOOCHANI

Author of No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison, winner of the Victorian Premiers Prize for Literature and Nonfiction and the ABIA General Nonfiction Book of the Year

A portion of the proceeds from this book will be donated to the Edmund Rice Centres Afghan Project in support of the community in Afghanistan.

CONTENTS

Appendices

WHAT KIND OF human beings are we becoming, when 65 million people do not have a safe place in their home countries? What kind of a world are we nurturing and accepting? The scale of todays global human tragedy is hard to comprehend and the causes complex, but we must try to come to grips with it: to understand, to tolerate, to empathise, to love.

At the Kabul Peace House, we follow a simple path of love. Without love, we and the universe are but empty atoms. Our community came about in response to forty years of war both from within and beyond our borders but it was also forged to bring about change, to foster new ways of thinking, to counter a fear of otherness.

The world has fixated on otherness, yet in every cell of ours, we share 99.9 per cent of the same human genome as those different from us: as humans we share a staggering sameness. When we hurt one another, even in the name of defence, we are hurting none other than ourselves. When we enrich and empower ourselves in the name of progress and ignore others, we may make some material gains, but we lose the most powerful force we have as sentient creatures: love.

What would you like the people of the world to do? I asked one of the members of our community, Taqi, recently.

To know one another, Taqi replied. We should reach out to understand each other as members of one family, instead of believing what the media or a few books portray. Does the rest of the world see us as human beings?

Sadly, governments rely on the narrative that many people are bad, ignorant and pugnacious, and should be guided and controlled by elites who are presumably good, intelligent and peace-loving. For too long, people have blindly accepted this black and white assessment. I too used to believe that the policies of our elites were reasonable, like when US President George W Bush launched the war on terror in 2001, triumphantly unloading bombs on an already devastated Afghanistan. The reality is that terrorism has increased five-fold since that time and is now worldwide.

What I saw unfold around me in Afghanistan shook my beliefs, including my philosophical or spiritual beliefs, and more importantly, my way of reasoning and feeling. I could no longer ignore my blind spots.

I faced the ugly possibility that many of us are unknowing accomplices in the promotion of terrorism, either as left or right or centrist supporters, or as Christian, Muslim or other dogmatic believers. We have watched on as local and foreign governments made life untenable in Afghanistan. Corporations and despots finance the elites, wrecking the earth with minimal accountability. The masses accept the status quo because current systems allow us to chase the very same things the elite are fighting over: money and power. We become them, the people we detest. The violence and inequality persist.

Unless, like at the Kabul Peace House, we begin wondering if we have been misled. Unless we learn how to question everything. To sceptics who may doubt us, come and live in Afghanistan. Perhaps only then will you know or believe that we all deserve to live in peace, with love, on a healthy planet.

Our community dreams that, without being intrusive, technology can be used compassionately to connect us with the seven billion other human beings on earth, and with our natural environment, if only to acknowledge their presence and to wish them well.

We sound idealistic? No, we refuse to believe that love is idealistic. Relationships are revolutionary and love their most powerful energy.

War separates us, often forever. And so too does migration, which is a fraught move for those who consider it. The prospects for a safe and secure migration, to a future with work, security and a semblance of welcome, have never been less assured. For Afghans now, is their fate better here or there or anywhere? Becoming refugees or asylum seekers may yet be the lonely outcome for some of our community.

Insaan in Dari means human. I chose it as my pseudonym because thats who I am and what I am thats who we all are. I like to believe we can evolve from Homo sapiens to Homo relationis: beings who are connected to each other. Taqi is wise: in order to know ourselves, we need to know others. In that future place of peace and connection we may be able to stand in solidarity with you and feel free enough and safe enough to tell you our real names.

With love,

Insaan

Kabul 2019

THE GENESIS OF this book was a trip I made to Afghanistan in 2016 as part of a small team of volunteer researchers, sent by the Edmund Rice Centre (ERC) to report on the safety of rejected asylum seekers returned to the country by the Australian government. The ERC works in research, education programs, advocacy and direct service, primarily with indigenous people, with refugees and asylum seekers, and with people from the Pacific struggling with climate change.

Since 2002 the ERC has been documenting the fate of rejected asylum seekers returned to their countries of origin by the Australian government.

A portion of the proceeds from this book will be donated to the ERCs Afghan Project in support of the community in Afghanistan.

As part of the preparations, I was excited but slightly anxious to be told, Youll be going in the winter, which is safer. The fighting usually stops because of the snow. News reports suggested attacks in Kabul were on the rise and kidnapping of Westerners was a serious threat.

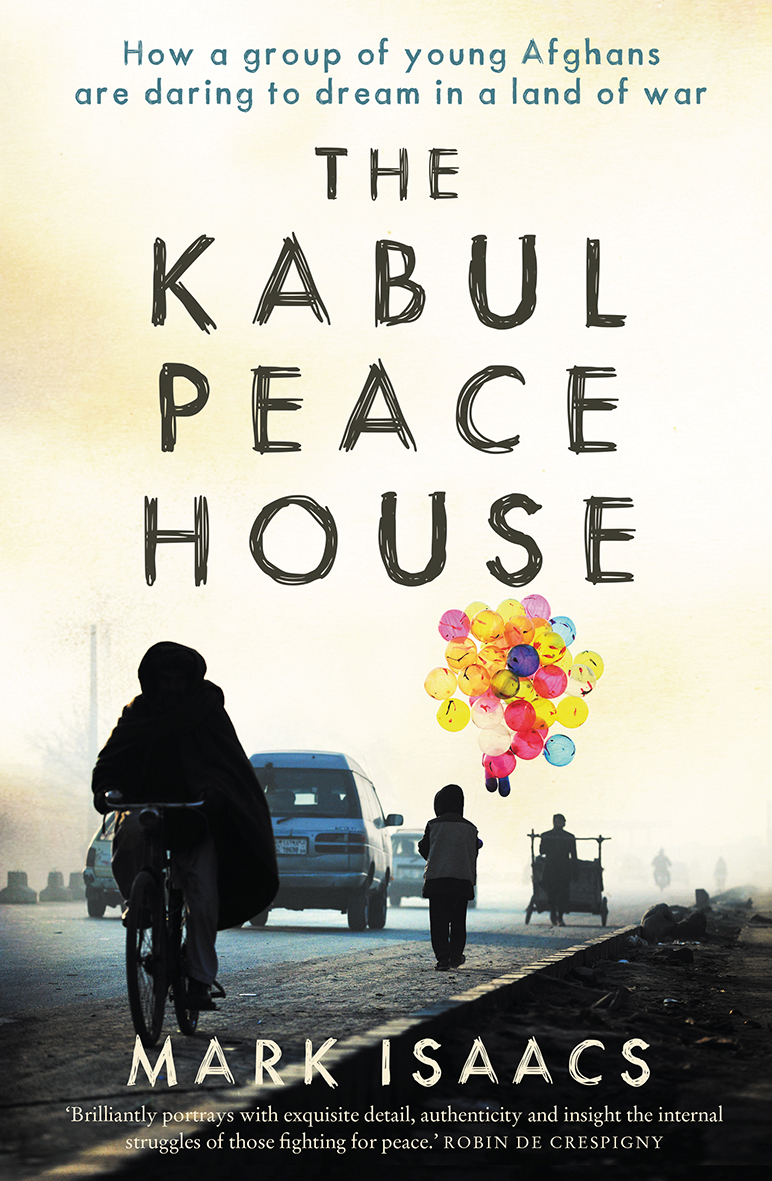

As part of our assignment we spent time with a group of volunteers, a multi-ethnic community living in a share house, creators of a peace park, a community centre and progressive community projects. At its heart is a manifesto, a group of young people and their mentor somehow, I had stumbled upon a peace movement in Afghanistan.

In answer to what can seem like never-ending violence in Afghanistan, the group formed to bring about change, to try to achieve peace where so many others had failed. Their ideology of equality, their compelling personal stories and the practical steps the group are making prompted me to make a second trip in 2017, to document how they have lived with war but have become a viable movement for peace.

IT IS IMPORTANT to understand that in a country as complex as Afghanistan it is impossible to accurately reflect the plethora of different views, experiences, opinions and histories of the country and its people. This is the story of the community, based on their experiences of Afghanistan.

This is a fully authorised work of creative nonfiction, based on hours of interviews and transcripts. While all the stories in this book are true, not surprisingly, names of individuals, places and identifying details have been changed to maintain the anonymity of the people involved. I refer to the group the collective, if you will as the community throughout.