This book is dedicated to my family:

My loving wife Donna, and my wonderful children

Danielle, Josh and Haley.

Familia OmniaFamily is all.

First published in 2016

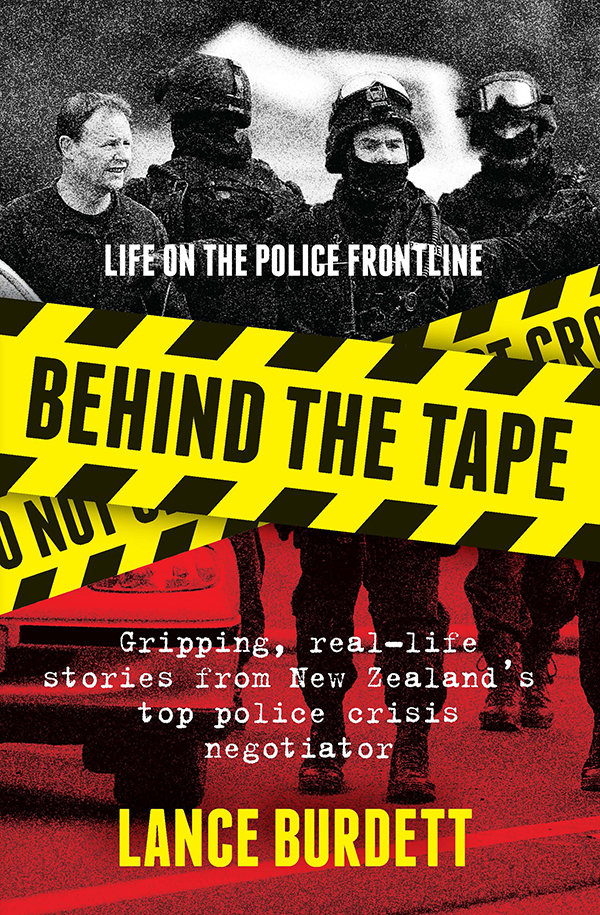

Copyright Lance Burdett 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Allen & Unwin

Level 3, 228 Queen Street

Auckland 1010, New Zealand

Phone: (64 9) 377 3800

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.co.nz

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

ISBN 9781877505607

eISBN 9781952534454

Typeset by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Facing adversity is tough. How you respond is really what determines the end result.

After a benign tumour was removed from my spine when I was 21, I was told I was unlikely to walk again. This devastating, life-changing event could have been negative, but resilience, spirit, determination, hard work and opportunity, combined with wonderful family, friends and employer support, transformed adversity into success.

In the pool at the 1996 Atlanta Paralympic Games, I won four Golds, one Silver and one Bronze. This led to a role in the Paralympic Games in Beijing 2008, and then London 2012, as Chef de Mission for an exceptional group of New Zealanders who had all faced adversity.

This amazing experience showcased just what can happen when people like these come together. They change perceptions, they change society, they inspire and excite.

I got to know Lance in his Police Liaison role with the New Zealand Games team at the London Olympic and Paralympic Games. He impressed me so much that I engaged him to work with my teams, helping staff to build resilience and deal with issues, as well as learn how to take control when faced with difficult or challenging situations at home or at work.

This book, about Lances unique experiences as a career police officer and his focused, insightful approach to dealing with the adversities and challenges of the job, will help anyone respond positively to adversity.

Duane Kale ONZM

Governing Board of the International Paralympics Committee

Head of ANZ Direct

CONTENTS

The confused odour of disinfectant, stale food, urine and fear fills my nostrils. The smell of prison is distinctive, like the smell of a dead person: once youve smelled it, you never forget it.

The brightly painted walls and floors do nothing to disguise the harshness of this environment. As I walk behind the corrections officer escorting me, our footfalls echoing, steel security doors open and close for me as though they know who I am. Its surreal and slightly disturbing. I feel completely alone, and its impossible to shake the irrational fear that when it comes time to make the return journey, the doors wont open. Theres a rising, claustrophobic terror in the thought. Its like those dreams you have where you get buried alive.

Through another set of doors. Theres noise now. People are shouting. I know who some of those people are, and Im glad there are steel bars between me and them. I know some of the things theyve done. And given this is the toughest cell block of New Zealands toughest prison, its a fair bet that the ones I dont know are no angels, either. The prison is in lock-down, but the inmates are shouting encouragement to the man who has caused all the fuss, egging him on, desperate for somethinganythingout of the ordinary to happen to break their routine.

Some yell abuse at me as I pass, but because I am dressed in casual clothing, they cant locate me on the food chain. I could be anyone: an inmate, a psychologist, a social worker, a tutor, a prison manager... They have no idea, but their default response is to abuse me. It would be worse if they knew what I am and why I am here.

I pay them no mind. Ive been called all sorts of stuff in my time. And my thoughts are already racing ahead to what Im going to find and how Im going to deal with it. Even after all these years, theres still a knot of anxiety in my guts about what it will be like if it goes wrong. And the potential for it to go wrong is high.

Around another corner, and Ive arrived. The scene is nothing like what I was expecting, even though if I have learnt anything in this job, its to expect the unexpected. Everything that could be movedchairs, tables, you name ithas been used to barricade the steel grille door of the recreation room and the door lock has been jammed with pieces of metal so that it cant be opened with a key. A couple of men are standing on this side of the door: one a prison manager, the other a prison officer. Theyre talking to someone inside the sealed-off room.

Beyond the barricade, theres an inmate strapped to a chair. His face and clothing are spattered with blood. Another inmate, tall and raw-boned, is pacing to and fro near him, apparently ranting to himself, although I cant make out what hes saying. The hard fluorescent lighting runs along the edge of an object hes holding, a raggedly sharpened piece of steel barpart of a cell window frame, as it turns outan improvised knife that prisoners call a shank. The scene looks contrived, like a stage setting, but this is all terribly real.

The prison staff turn slightly as I approach, and the prisoner notices. Abruptly, he stops pacing. His eyes, wide and helpless with rage and fear, fasten upon me.

Who the fuck are you? he asks.

Its as good a question as any, I think, and I take a deep breath.

This is more like it, I thought to myself.

Yeah, the man was saying. It was a Honda. A white Honda. And it was weird, because the guy didnt only wash his back window. He opened the boot and washed in there, too.

I was on a homicide enquiry, interviewing a witness. The trial of the accused, who was facing a charge of murder, was already underway in the High Court, but that didnt dampen my enthusiasm. I was one week out of Police College, and here I was investigating a murder. It was just like TV, and it sure made a change from picking up muffins.

After my graduation from Police College in 1993, I had found myself in a kind of limbo. Police numbers are tightly controlled for both monetary and political reasons so I had to wait until there was a vacancy for me. Id actually been posted to Auckland City, but I really wanted to be in Hendersonthats where my family was, and I wasnt sure Id be able to organise transport to get into the city for work. In those days, you didnt have any choice about where youd be working when you left the college. They asked where you wanted to work but then sent you wherever the need was greatest. I could easily have ended up somewhere in the South Island if thats what was decided for me. Instead, I had managed to find another graduate whod been assigned to Henderson but who wanted to work in the city. We were waiting to see if our proposed swap had been approved, and here I was, not even officially posted to a police station, in the thick of real police work.

It was unusual for a freshly graduated cop to be assigned to a murder, but on my very first day at the Henderson station, I was summoned to meet the detective inspector who was running the investigation. He was affectionately known as Gentleman Bert, because thats what he was: a true gentleman and an old-school policeman. He was very softly spoken and he sat me down and gently explained what my role in the case would be.