Contents

Chapter Ten: A Certain Tension

Introduction

The Dream and the Reality

Things that were unthinkable yesterday suddenly, today, theyre here.

And what used to be safe and familiar wont be, tomorrow.

Count to ten dont get angry and start from the beginning.

Youve got something to say so dont give up but choose your words carefully.

From Count to Ten, a song by the Israeli pop group Tea Packs

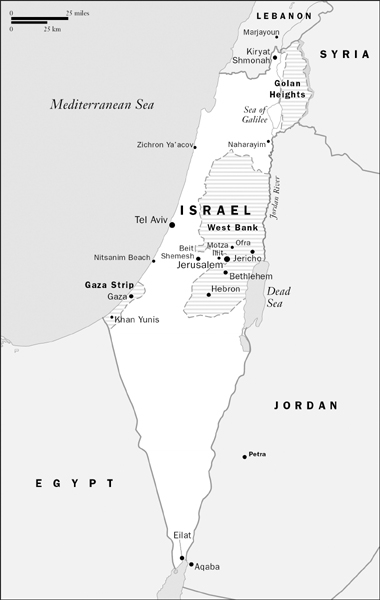

On the Wednesday, I ate a late lunch with Sharon and Alvin, two colleagues from work, at the Village Green, a vegetarian restaurant on Ben-Yehuda Street. We sat in the shade of a sun umbrella, munching our bean sprouts, gloomily comparing the sizes of our overdrafts.

By Thursday afternoon, the Village Green looked a little different. Its huge plate-glass storefront window had been shattered, its wooden chairs reduced to firewood. A young man in his early twenties, a Palestinian, had strolled along Ben-Yehuda at around three oclock carrying a traveling bag, conversing easily with two of his friends. He had stopped outside the Village Green; his friends had positioned themselves outside two other shops nearby. Then all three of them had pressed their buttonsthree, so that their recruiters could emphasize how many were ready to die for the cause.

For hours afterward, rescue workers were mopping up their blood and scraping bits of their dismembered bodies off the walls and the tables and the chairs at the Village Green, off the fedoras and the trilbies in the display cases at Fuersters Hat Shop farther up the road, off the bridal gown hanging lopsidedly from the mutilated mannequin in the dress shop next door.

Their blood, and the blood of the five Israelis they had killed.

While hundreds of horrified, ghoulishly curious Jerusalemites were kept behind police barriers all along the street, I walked through the bomb zone with the devastation still fresh. Wonderful thing, a press card. It gets you access to places other folks just cant go near. I looked at a large chunk of a bombers torso oozing blood from beneath a piece of white plastic sheeting. I heard one of the rescue workers call out from a caf, as I scrunched past on the broken glass, Aaron, theres a foot here. I smelled the faint but unmistakable odor of burned fleshjust like a summer barbecue, made revolting only by the context. And I saw the remains of that green sun umbrella wed sat under twenty-four hours earlier at the Village Green. The cloth had been ripped away by the force of the blast, but the white metal frame was still there, spattered with blood. Chunks of human flesh were hanging from it, like scraps in a deranged butchers display.

Almost everybody who has ever been to Israel has walked down Ben-Yehuda Street. My wife, Lisa, when we were at university, used to waitress at the Village Green; her roommate waitressed at the caf across the street. Ben-Yehuda is where American seminary students hang out when ducking classes, where tourists shop for souvenirs, where locals grab a cheap felafel or shwarma lunch, where the tarot-card readers and the astrologers drink Turkish coffee during the long waits between gullible customers, where the disciples manning the outreach stand of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe attempt to persuade the secular male pedestrian traffic to don a skullcap, strap on tefillin (phylacteries), and say a prayer. And so, more than with any of the dozen-plus suicide bombings in the past few years, this Ben-Yehuda blast had everybody thinking, That could have been me.

But it really, really could have been meand Sharon and Alvin. All wed have had to do was eat lunch at the Village Green on Thursday instead of Wednesday.

My wife and I, naturally, discussed at length my closeish brush with death (as compared to the general, ongoing, slightly more distant brushes with deaththe blasts in the vegetable markets where we sometimes shop, the late-night shootings on roads weve often usedto which all of us in Israel have tried to become accustomed over the years). But, youll understand, we did not raise the matter of Daddys lucky break with our eldest son, Josh, who was only five at the time. Still, the raw details of the bombing did not escape him, nor did we try to shield him from them completely. This is our reality, his reality, and he has to deal with it somehow, while his parents offer reassurance and try to explain the inexplicable. He watched news reports on television, overheard conversations, saw the newspaper photographs. His kindergarten teacher had the kids sit in a circle, their open, innocent faces turned anxiously toward her, to talk about the bomb, their fears, the dead people, the bad guys who had come to Jerusalem to kill.

And three days later, after Joshs five-year-old mind had done its best to grapple with the overload, as his mother and I and his younger brother and his baby sister drove home together from my office in late afternoon, he blurted out from the backseat: If you both get killed, whos going to make our sandwiches?

In a way, it is because of that question that Ive written this book. Because my generous, sensitive eldest child, whom Ive had the arrogance, or the stubbornness, or the blindness, or the faith, to try to bring up in Israel, is so attuned to the wicked violence of the world into which Ive pitched him that he has already partly reconciled himself to the loss of either his mummy or his daddy and now is progressing toward preparing for the loss of us both. People are dying everywhere, he was saying, and I dont understand why. Im scared one of you is going to die too, and that would be terrible. But what am I going to do, what is Adam going to do, what is Kayla going to do, if you both get killed? Whos going to wash us and dress us and read to us and hug us? And whos going to make our sandwiches for kindergarten?

I know that putting this down on paper isnt going to alter anything dramatically. It wont stop the bombs or alleviate the hatreds. But it just might open some minds. And it might help me clarify my own thinking about living here: Whether I owe it to my family to keep doing what I came here for in the first placeplaying a unique role, however small, in shaping the first Jewish state in two thousand years, completing a circle of history, bringing our modern Jewish family back to the land of its roots, to the city where my ancient royal namesake built his capital three thousand years ago, to be free, a majority, in our own country, to make our own decisions, and then live and die by them. Or whether Lisa and I ought to take the kids somewhere calmer and safer. I have the arrogance to worry about how growing up in a West Bank settlement may impact my sisters children, but what am I doing to my own, exposing them to all the anger and bloodshed? When you have children, you take more care crossing the road, you drive a touch more carefully. And, in my case, you start looking more deeply at how and where youre living, your reasons for being here, and whether theyre still validwhether what was right for a student, or a single man in his twenties, is right for a married man with three kids a decade later.

The theory, the way I absorbed it through years of largely mediocre Jewish education in London, was that this Israel was supposed to be the safe haven for the Jews, the refuge for the persecuted people, the democratic, free, independent homeland, awash in a sea of Arab hostility but holding its own and slowly rolling back the tide of hatred, gradually eliminating the existential threats, making its peace with its neighbors.