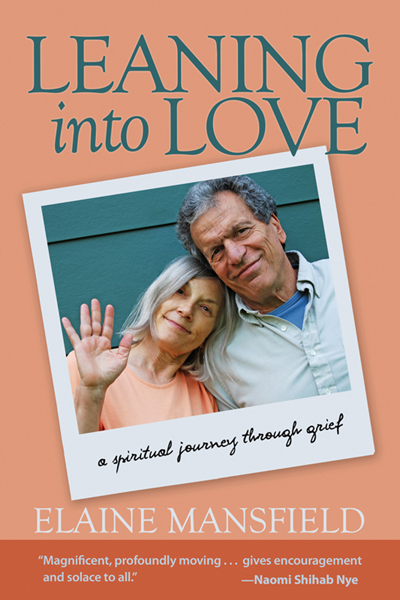

Copyright 2014 by Elaine Mansfield

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means electronic, chemical, optical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN-10: 1-936012-72-3

ISBN-13: 978-1-936012-72-5

eISBN-10: 1-936012-73-1

eISBN-13: 978-1-936012-73-2

Back cover photo: Susan Kahn / Colgate University

Front cover photo: Vic Mansfield 2007

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014944219

Publishers Cataloging-In-Publication Data

(Prepared by The Donohue Group, Inc.)

Mansfield, Elaine.

Leaning into love : a spiritual journey through grief / Elaine Mansfield.

pages ; cm

Issued also as an ebook.

ISBN-13: 978-1-936012-72-5

ISBN-10: 1-936012-72-3

1. Mansfield, Elaine--Family. 2. Grief--Psychological aspects. 3. Husbands-Death--Psychological aspects. 4. Love. 5. Widows--United States--Psychology.

1.Title.

BF575.G7 M36 2014

155.9/37092

2014944219

Published by Larson Publications

4936 State Route 414

Burdett, New York 14818 USA

https://larsonpublications.com

23 22 21 3019 18 17 16 15 14

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Vicmy lover, husband, spiritual partner, and best friend.

People do not

pass away.

They die,

and then

they stay.

Naomi Shihab Nye

(with permission of the author)

Contents

Oceans

I have a feeling that my boat has struck, down there in the depths, against a great thing.

And nothing

happens! Nothing Silence Waves.

Nothing happens? Or has everything happened, and are we standing now, quietly, in the new life?

Gone Beyond. Oh, What an Awakening.

Hes conscious, the nurse says. I trust this Vietnam vet with his acne scarred face and tender resigned heart. His sad eyes help me face whats coming. The two of us stand next to a bed in the oncology unit of Strong Hospital and look over Vics limp body.

He can hear you, the nurse says,but hes too exhausted to respond. You can ask him to squeeze your hand.

Yes, I could ask Vic to squeeze my hand if he loves me. But I dont doubt his love. I can ask him to squeeze if he hears me, but he doesnt need to hear me. He needs to die, so I dont call him back to life and to me, but let him stay with the hard labor of breathing. I touch him and inhale his scent, rub oil into his hands and feet, and pray for strength to let him go. Ive walked with him to the threshold of death and hung my feet over the ledge. I feel the vastness of the abyss, but can go no further.

For two years Ive tried to save him. Weve both tried, but there are no more escape routes. After years of struggle, his gentle passage opens my heart and stills my mind. This quiet death is his last gift to me, even as I weep and whisper my good-byes. Just after midnight, he exhales. I wait for an inhalation that does not come.

I dont know how to live without this man. I depend on his brown eyes beaming at me. For forty-two years we loved each other, meditated together, transformed our land, raised our sons, and shared our dreams and sorrows. I dont know who I am without him.

I sit with his body for six hours, until an orderly takes him away in a body bag. Then I walk down the dark hospital corridor toward the elevator, my shoulder leaning into my son Anthony. Were followed by four friends who stayed with Vic and me at the hospital the last three days. Im exhausted and numb, but also relieved. I dont have to watch his suffering anymore. Now I begin to deal with my own.

We take the elevator down and walk toward the hospital lobby, shading our eyes from the sun glaring through the floor-to-ceiling windows. People scurry, grasping coffee cups, pushing to punch in before seven a.m. They are serious and self-absorbed, their eyes averted. They are behind a glass wall, in another world, on the side of the living. I stand on a threshold where death feels closer than life.

We find my Subaru in the parking garage and stack Vics clothes and laptop on the back seat. Lingering, we stand in a helpless clump, softened by the mystery of death we just witnessed. Its not enough to hug and thank these generous friends for accompanying me on this journey, but its all I have to give.

Are you OK to drive? Anthony asks.

Yes, I answer. Follow me.

I steer down the parking garage ramp, driving slowly so Anthony can catch up in his rental car. I stop at the parking attendants glass-windowed booth. My body knows how to count the money and pay the parking fee. Isnt there a discount if the person you brought here has been left behind in the morgue? Its a ghoulish private joke the young parking lot attendant wont get. Im a stranger, just returned from the underworld. Ive seen death, raw and unstoppable, and understand that my own death is not a distant thing.

My body knows how to navigate this world, knows the way to the airport where Anthony can return his car. I grip the steering wheel, feeling both sharply awake and vaguely disembodied. Outside the rental car return, I move into the passenger seat and let the June sun bathe me with warmth.

Anthony drives toward home in the slow lane on the New York State Thruway. We travel over the foreign soil of this world, strangers to the usual concerns of the day.

Are you OK? Lauren asks when she calls the next morning. Lauren Cottrell is one of the friends who attended Vics death. She helped me swab his mouth, hold his body, chant prayers, and read passages out loud from The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying.

Nothing is solid. Its all a dream, I tell her. The mortician said that if I want to put anything in Vics cremation box, it should happen today before his body begins to decompose. It feels important to do this right, but Im floating and spinning.

Im on my way, Lauren says. Ill sit quietly or help however I can.

I stand at the bathroom sink and inspect the drawn woman in the mirror with dark circles under her eyes. Her gray hair falls in limp clumps and her red eyes are puffy, but nothing remarkable has changed on the outside. I still have a body and it needs a shower. The hot water pounds my tight neck. It feels good, just like it did when I took a shower in Vics hospital room a few days ago. Im grateful for the small pleasure. I gel and brush my hair for the first time in days, put on tan workout pants, my favorite apricot tank top, and slip my bare feet into Birkenstocks. I glance in the mirror again. How am I supposed to do this? Not expecting a response, I go downstairs, make myself a bowl of yogurt, and brew a cup of mint tea to settle my stomach.

My older son David joins me on the back porch. He arrived late last night. Purple shadows under his brown eyes tell of yesterdays long sad journey from the mountains of Slovakia. He knew he wouldnt get home in time to see his dad alive.

The warm morning light helps me find my bearings. Finches jockey for perches at the bird feeder. Red-winged blackbirds and blue jays complain. I sit at the picnic table inhaling the steam of my mint tea, trying to focus my racing mind on the list of tasks. Do I want to pay for an obituary in Vics hometown newspaper, even though he hasnt lived there for fifty years? Should the memorial service be Sunday afternoon or next month? How do I plan a memorial service anyway? What do I do about the flower arrangements with their cloying smells and pastel colors? They are delivered one after another, and my house reeks.

Lauren walks around the side of the house toward the porch, moving with a bounce even though she hasnt slept for days either. She hugs Davids sturdy weightlifters body and sits next to me, wrapping an arm around my waist. Her long brown hair is damp and smells faintly of shampoo. I hear Anthony grinding coffee in the kitchen and catch a whiff of French roast. He joins us on the back porch, his eyes just as red and swollen as Davids and mine.