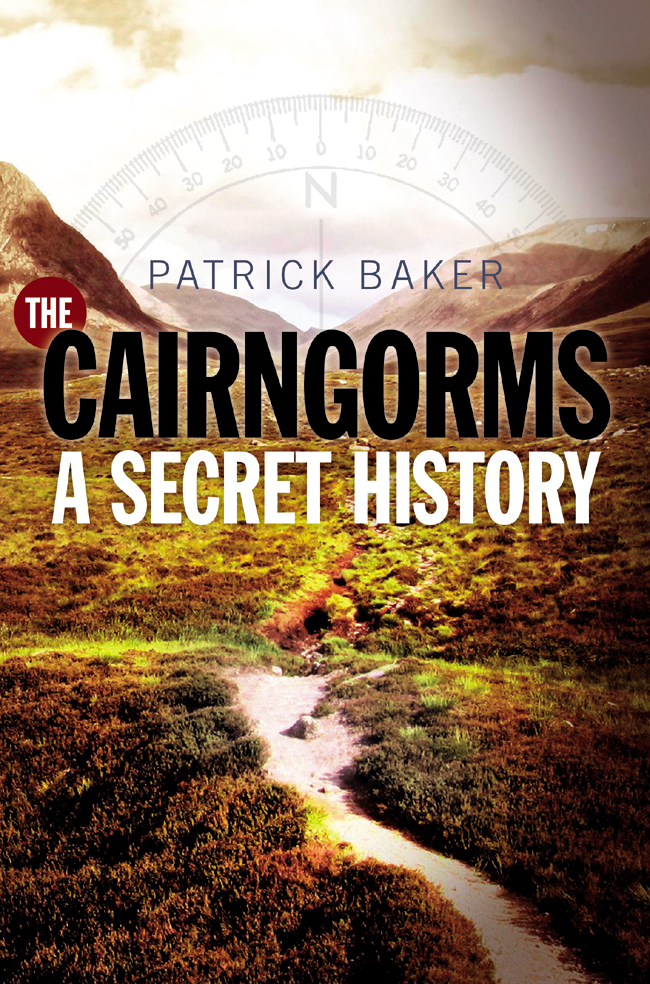

THE CAIRNGORMS

A Secret History

Patrick Baker studied Business, Finance and Economics at the University of East Anglia and gained a postgraduate qualification in Publishing from the Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen. He has worked in the publishing industry for many years editing and producing academic journals and is currently a writer for an investment management company. A keen outdoor enthusiast, he has walked and climbed throughout Scotland and Europe. His book Walking in the Ochils, Campsie Fells and Lomond Hills (Cicerone) was published in 2006.

This eBook edition published in 2014 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Text and photographs Patrick Baker, 2014

The right of Patrick Baker to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publishers.

ISBN: 978-1-78027-188-0

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-809-4

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Contents

Illustrations

Dedication

For my wife Jacqui, and for my children Isla, Rory and Finn, with all my love.

Secret Histories

The exploratory urge moves every man who loves the hills.

W. H. Murray

For a few fleeting seconds, my mind defaulted to known surroundings: to my bed at home and a drowsy feeling of safety and cosiness. The sensation quickly passed; I came to shuddering in the darkness, temporarily disorientated by the cold, but slowly remembering where I was. It was midnight on the summit of the Cairngorm plateau and I hunkered down further into my sleeping bag, suppressing a mild sense of panic about the possible onset of hypothermia and questioning the wisdom of spending the night alone at over 4,000 feet.

For almost an hour I lay awake watching the skys patterns. Jigsaw patches of cumulus clouds scudded overhead, tesselating and decoupling from each other against the dark firmament. An icy north-westerly rolled across the nights empty spaces. It rattled through my bivouac bag, inflating, then collapsing, pockets of cold mountain air all around me. Sleep seemed impossible, and eventually a restless, nervous energy got the better of me. Tired of shivering and too cold to stay still, I left my shelter and began to tread the nightscape of the plateau.

I walked roughly eastwards following a tiny spring-fed stream whose surface glinted like molten metal. The wind gusted steadily at my back, hustling against the material of my jacket and nudging me forward with every step. On the plateaus western rim the moon drifted large and low, and ahead of me the land dipped into a shallow depression at least half a kilometre wide. Dozens of wellsprings collected there, each throwing back the moonlight like tiny droplets of mercury. Beyond the watershed, the horizon rose in a gentle incline, edging towards its uppermost point, the summit of Braeriach: the second-highest mountain in the Cairngorms and the third-highest peak in Britain.

From the abstract thoughts that accompany complete solitude, a daft, random notion entered my mind: unless, for some equally unfathomable reason, someone else was spending the night on either of the UKs two higher places, Ben Nevis or Ben Macdui, I realised that I was, at that moment, the highest human being in Britain. I was, in fact, probably higher than anyone else on the western peripheries of Europe.

For a few seconds, the thought unbalanced me, tipping me back again towards panic. What was I doing? I was dozens of kilometres and a thousand elevated metres from the nearest place of human habitation, effectively stranded until sunrise in one of the countrys most inhospitable natural environments. Alone in the high-altitude darkness, the realisation of my self-enforced remoteness sent a brief, electric current pulsing through my stomach. I felt foolhardy, and a bit naive.

Suddenly my plan seemed rather ridiculous. Several months earlier, sitting at my kitchen table with the last shafts of evening sun cutting into the room, the thought of making a series of journeys to explore some of the most desolate and seldom visited parts of Britains wildest mountain range had seemed like a good idea. What better way to find out more about a place that over the years I had become slightly obsessed with?

Back then, the practicalities of the project had hardly even registered with me. It would take a while, of course: a year perhaps, in between the commitments of work and family life; but it would be feasible, even enjoyable. They were to be adventures, unconventional mountainous escapades to places I would have never normally thought of venturing.

Now, though, at one oclock in the morning, jogging on the spot to keep warm, on top of Britains third-highest mountain, I couldnt help wondering if this was more than I had bargained for.

I had first visited the Cairngorms when I was in my early twenties. I was on a training course for would-be mountaineers, learning the rudiments of winter hillcraft from an instructor hell-bent on leaving behind any of us who were too slow to keep up. By early afternoon we had picked our way up a steep ice bank in Coire an t-Sneachda, one of the towering, snow-encrusted Northern Corries. Perhaps it was the oxygen-depleted exertion, the rush of endorphins or the elation at finally pulling up on to the plateau edge, but I was momentarily overcome by what I then saw.

I stood breathless, staring out across a snowbound territory of ice-fields, turreted island summits and kilometres of crystalline brightness that stretched as far as my eyes could see. Then, as now, I felt an utter bewilderment at the sheer size of the Cairngorms. No other area of Britain is so immensely high over such an immensely large area. Its elevation and geographical extent make it unique: a monolithic expanse of mountainous granite landmass equivalent in size to Luxembourg and containing five of the sixth highest peaks in Britain.

Accordingly, it is known as a place of extremes and cruel asperities, of unparalleled topographical and altitudinal circumstance. Snow falls here in every month of the year and lies permanently in its coldest recesses. Gales regularly batter the plateau with such ferocity that wind-speeds have reached over 170mph. Temperatures and conditions are subarctic in their severity and fatalities are recorded here regularly.

But beyond its immediate first impressions, its hostile bleakness and prodigious expanse, an alternative identity of the range also exists. It is a corresponding but often concealed character, described by the modernist poet and novelist Nan Shepherd, as the living mountain, in her unashamedly eulogistic book of the same name. For like all wild places, the Cairngorms harbour hidden narratives: geological, animal and human past events and contemporary passages which are rarely acknowledged in the same way as urban and industrialised histories, but are nonetheless evidenced within the landscape; if, of course, you know where to look.

It was the Cairngorms, more than any other remote or mountainous area that I knew, which seemed to retain and perpetuate these secret histories. It seemed, as well, that despite or perhaps because of its fearsome wildness, there were stories and mysteries here that were more potent and intriguing than anywhere else I could think of.