T RIBES

WITH

F LAGS

Adventure and Kidnap in Greater Syria

CHARLES GLASS

Ebook edition first published in Great Britain in 2012 by

HarperPress

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

7785 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in the United States in 1990 by Atlantic Monthly Press

First published in Great Britain in 1990 by Secker & Warburg

TRIBES WITH FLAGS. Copyright Charles Glass 1990, 2012

The right of Charles Glass to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Ebook Edition September 2012 ISBN: 978-0-00-750018-5

Version 1

FIRST EDITION

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

http://www.harpercollins.com.au/ebooks

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

2 Bloor Street East - 20th Floor

Toronto, ON, M4W, 1A8, Canada

http://www.harpercollins.ca

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1

Auckland, New Zealand

http://www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

London, W6 8JB, UK

http://www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

10 East 53rd Street

New York, NY 10022

http://www.harpercollins.com

Charles Glass is the author of Americans in Paris, Tribes with Flags, The Tribes Triumphant, Money for Old Rope and The Northern Front:An Iraq War Diary. A world-famous journalist and broadcaster, he was Chief Middle East Correspondent for ABC News from 1983 to 1993, and has covered wars and political upheaval throughout the world. His writing appears in the Independent and the Spectator. He divides his time between Paris, Tuscany and London.

www.charlesglass.net

Americans in Paris: Life and Death under the Nazi Occupation 19401944

The Northern Front: An Iraq War Diary

The Tribes Triumphant

Money for Old Rope

For Julia, Edward, George, Hester,

Beatrix and Fiona

and to the memory of Mouna Bustros

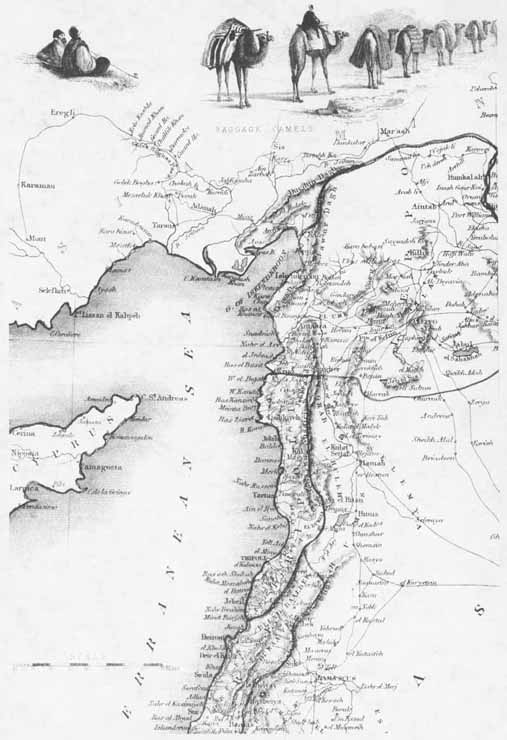

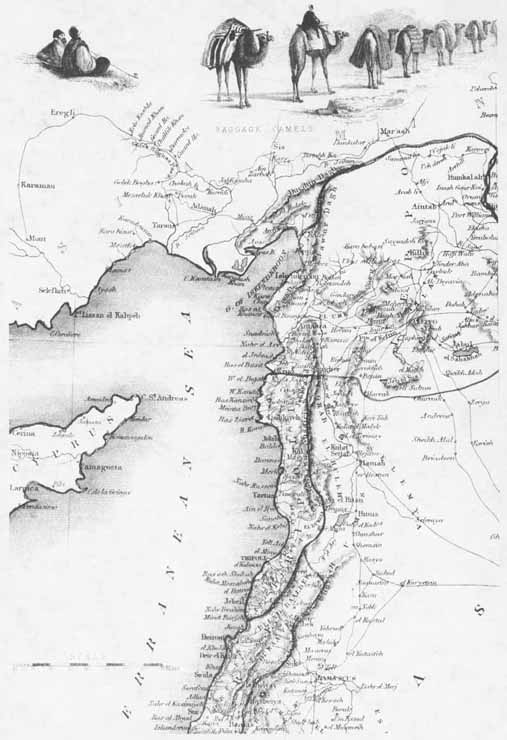

Detail from Syria, Tallis Atlas, 1841

CONTENTS

A man may find Naples or Palermo merely pretty;

but the deeper violet, the splendour

and desolation of the Levant waters

is something that drives into the soul.

James Elroy Flecker

Beirut, October 1914

Twenty-five years ago, I traveled by land through what geographers called Greater Syria to write a book. The journey began in Alexandretta, the seaside northern province that France ceded to Turkey in 1939, and meandered south through modern Syria to Lebanon. From there, my intended route went through Israel and Jordan. My destination was Aqaba, the first Turkish citadel of Greater Syria to surrender to the Arab revolt and Lawrence of Arabia in 1917. For various reasons, my journey was curtailed in Beirut in June 1987. (I returned to complete the trip and a second book, The Tribes Triumphant , in 2002.)

The ramble on foot and by bus and taxi gave me time to savor Syria in a way I couldnt as a journalist confronting daily deadlines. People loved to linger over coffee and tea, play cards, and talk.

Many of the civilian members of the Baath Party, whose founders claimed to believe in secularism and democracy, deserted its ranks when the party took power in 1963. They rejected the militarization of the party, which kept power not through elections but by force of the arms of its members within the army. Among those who left the party was the father of Rulla Rouqbi. I met his daughter a few weeks ago at the hotel she manages in Damascus. Faissal Rouqbi had died in April 2012, and this explained why the attractive fifty-four-year-old was dressed in black. A vigorous supporter of the revolution that began in Syria a year earlier, she believed hers was the same struggle her father had waged against one-party military rule.

I was questioned twice by the security forces, she told me in the hotels coffee shop, which looks out onto a busy downtown street. They did it just to show me they know what I am doing and they are here. She said that, because young dissidents gathered in her coffee shop with their computers, the police cut the hotels WiFi connection. Nonetheless, several young people were there discussing the rebellionmuch as their forefathers did in the old cafs of the souks that the French destroyed to put down their revoltsover strong Turkish coffee or newly fashionable espresso.

The rebellion against tyranny was by 2012 turning into a sectarian and class war that threatened to destroy Syria for a generation and drive out those with the talent, education, or money to thrive elsewhere. Neither side spoke of conciliation. The endgame for each was the destruction of the other. Foreign backers appeared, as in Lebanon from 1975 to 1990, to encourage confrontation in their own rather than Syrian interests. Nothing had changed since Britain and France occupied the Ottoman provinces of Greater Syria during World War I.

A glimmer of hope came from the economist Nabil Sukkar, formerly with the World Bank. The opposition is not going to retreat, he told me in Damascus. The stalemate could last to 2014. Bashar al-Assads term of office was scheduled to end in that year, when, Sukkar believed, he could stand down without losing face or having his Alawite community punished. He continued, For [Kofi] Annan to succeed, there has to be compromise from both sides. The regime must stop killing, and the opposition must stop smuggling [arms]. And foreigners must stop sending arms. Then there can be a cease-fire and a transition government. However unlikely that seems today, it could work if Russia and Iran compel the regime and the United States, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar push the opposition to achieve it. Otherwise, Syrian will fight Syrianjust as the Lebanese didin what the respected Lebanese journalist Ghassan Tueini called a war for the others.

Three great fears dominated the uprising of 2011 and 2012: that the regime would emerge stronger and more violent; that Syrias traditional tolerance and respect for people of different religious and ethnic communities would falter if a strongly Sunni Muslim fundamentalist regime replaced it; and that, with neither side able to destroy the other, the conflict would escalate and linger as Lebanons did. Nowhere were these fears more apparent than in my favourite Syrian city, Aleppo.